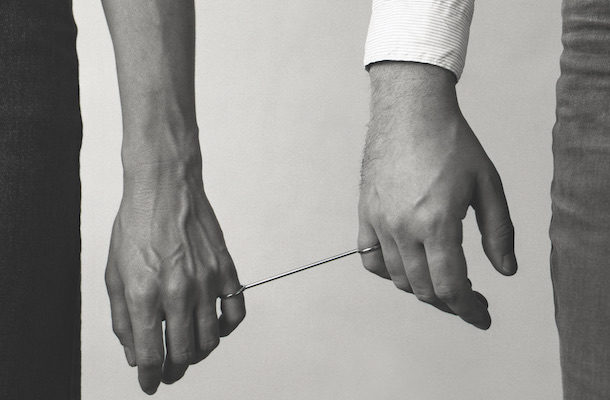

Ring für zwei Personen (Ring for Two Persons), Otto Künzli, 1980. OTTO KÜNZLI PHOTO.

Ring für zwei Personen (Ring for Two Persons), Otto Künzli, 1980. OTTO KÜNZLI PHOTO.

Feature

Two for the Show: Jewelry’s Power Couples

JEWELRY IS THE MOST INTIMATE ART FORM, characterized by a symbiotic relationship with the human body. It functions by touch, embracing one’s ears, neck, chest, wrists, and fingers. Jewelry is seductive. Not surprisingly, many jewelers fall in love with one another. In fact, some of the most notable jewelers of the past seventy years—including several of the field’s superstars—have chosen to marry. Might it be the allure associated with jewelry that attracts these artists romantically? Or simply a common aesthetic and shared passion? Whatever the reasons, making jewelry evidently makes for love. Some jewelry-making couples who cohabitate also collaborate, while others are amorous partners but create artworks autonomously. However one looks at it, the work they generate, either alone or together, would not be the same without the closeness of their relationships. Unlike contemporary jewelry couples, most of whom met in art school, mid-century modernist jewelers found their mates in distinctive ways.

Emmy van Leersum and Gijs Bakker

Plastic Soup bracelet by Bakker, 2012. Plastic straws, gold plated. Courtesy CHP…? Jewelry.

The social revolution of the 1960s begged for new manners of personal expression in clothing and jewelry. Artist-designers such as Emmy van Leersum and Gijs Bakker in the Netherlands and Wendy Ramshaw and David Watkins in the United Kingdom were visionaries who welcomed the challenge. It was the first time an idea had dictated materials and techniques, and that jewelry’s potential for dynamic interaction with the human body was considered. Van Leersum and Bakker—now a lauded industrial designer and co-founder of Droog Design, as well as an innovative jeweler—initially met while both were students at what is today the Gerrit Rietveld Academie in Amsterdam. Van Leersum was a twenty-eight-year-old former nursery school teacher; Bakker was sixteen. They subsequently reunited at Konstvack in Stockholm, where both continued their study of metals.

Gijs Bakker and Emmy van Leersum in their Amersfoort studio, 1971. Eva Besnyo Photo.

In 1965 they opened a shop together, Atelier voor Sieraden, in Utrecht. They married in 1966, and launched a collaboration that would change the course of contemporary jewelry. In addition to designing jewels that pushed the limits of structural geometry and mathematical forms, van Leersum and Bakker brought studio jewelry to the “catwalk,” linking it to fashion shows, and, through a cutting-edge mix with other mediums, presenting it as performance art. When van Leersum and Bakker’s monumental aluminum collars and cuffs were first exhibited in 1967 in London, their designs were deemed so futuristic that an article about them in the Daily Sketch of October 11, 1967, was titled: “What the Girls Will Wear in AD 2000.”

Gijs Bakker and Emmy van Leersum’s Clothing Suggestions, 1970, in polyester, nylon, cork, plastic, wood. Ton Baadenhusen Photo.

Among their most avant-garde concepts was the Clothing Suggestions series from 1970—formfitting tricot apparel that expanded and distorted the body’s contours by means of wood, plastic, and cork forms, or altered specific portions, such as the knees, elbows, genitalia, and breasts, with hardened polyester bulges. The garments were used by the Nederlands Dans Theater in 1970 for its ballet Mutations. In 2014 the Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam, featured Bakker’s and van Leersum’s designs in The Gijs + Emmy Spectacle, an exhibition that sought not only to chart the duo’s progressive ideas but recreate a runway show of their works that was presented at the museum in 1967 during Edelsmeden 3, a group show that featured promising young silversmiths. The curator used vintage clips and a newly made video, enhanced by the original musical accompaniment, along with actual garments and jewelry by the couple to evoke the spirit of the 1967 production. In her book Gijs Bakker and Jewelry, author Ida van Zijl writes: “The formal similarities between their works in the period 1963–1976 are so great that Bakker and van Leersum are almost always named in the same breath . . . an inseparable duo that was responsible . . . for the revolution that occurred in the 1960s.” Van Leersum died of cancer in 1984 at fifty-four. The grief-stricken Bakker began to make wistful neckpieces of laminated flower petals—a format that has become one of his most beloved and imitated styles.

There are many other noteworthy couples working in jewelry today, such as Germans Norman Weber and Christiane Förster, Georg Dobler and Margit Jäschke, and Bettina Dittlmann and Michael Jank; Italians Annamaria Zanella and Renzo Pasquale; Israel-born Attai Chen and his German-Iranian partner, Carina Shoshtary; and Stockholm-based Adam Grinovich and Annika Pettersson, and Beatrice Brovia and Nicolas Cheng. Brovia and Cheng, like the others, maintain separate practices, but since 2011 have collaborated on a joint project that focuses on interdisciplinary material research and craft discourse through installations, objects, and jewelry. All in all, whether by a common intellect and aesthetic sensibility, compatible theoretical bent, physical attraction, or simply the mystery of love, one fact is certain: couples who make jewelry turn each other on.

Toni Greenbaum is an art historian specializing in twentieth- and twenty-first-century jewelry and metalwork.

This article has been updated to correct two errors that appeared in our Summer print issue: the proper photograph is shown with the discussion of Sam and Carol Kramer; and the caption to the image of Gijs Bakker and Emmy van Leersum’s Clothing Suggestions has been corrected.