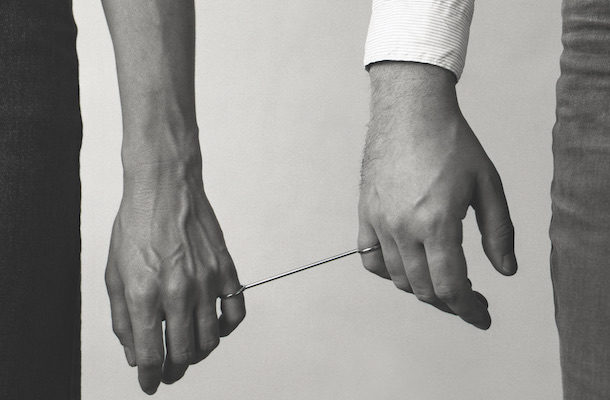

Ring für zwei Personen (Ring for Two Persons), Otto Künzli, 1980. OTTO KÜNZLI PHOTO.

Ring für zwei Personen (Ring for Two Persons), Otto Künzli, 1980. OTTO KÜNZLI PHOTO.

Feature

Two for the Show: Jewelry’s Power Couples

JEWELRY IS THE MOST INTIMATE ART FORM, characterized by a symbiotic relationship with the human body. It functions by touch, embracing one’s ears, neck, chest, wrists, and fingers. Jewelry is seductive. Not surprisingly, many jewelers fall in love with one another. In fact, some of the most notable jewelers of the past seventy years—including several of the field’s superstars—have chosen to marry. Might it be the allure associated with jewelry that attracts these artists romantically? Or simply a common aesthetic and shared passion? Whatever the reasons, making jewelry evidently makes for love. Some jewelry-making couples who cohabitate also collaborate, while others are amorous partners but create artworks autonomously. However one looks at it, the work they generate, either alone or together, would not be the same without the closeness of their relationships. Unlike contemporary jewelry couples, most of whom met in art school, mid-century modernist jewelers found their mates in distinctive ways.

Svetozar and Ruth Radakovich

Ruth Radakovich and Toza Radakovich in their Rochester, New York, studio, 1950s. Terry Lindquist Photo.

At the same time, there was vigorous activity in jewelry studios on the West Coast. Encinitas, California, was home to metalsmiths Svetozar (“Toza”) and Ruth (née Clark) Radakovich, a couple whose saga of Cold War intrigue is the stuff of suspense novels. Ruth and Toza met in 1946 in Yugoslavia, when both were working for the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. Ruth was an American volunteer and Toza, an employee in the art department. Toza was also a Yugoslav national, who was closely watched and briefly imprisoned under the country’s Communist regime. Although Ruth had gone back to the United States, she returned to Europe to try to obtain his release. She dispatched messages to him, hidden in pill bottles and beneath the surfaces of paintings. Her most daring effort was a small boat intended for his escape—sent piece by piece from her base in Bari, Italy, concealed among the items in care packages. Although Toza successfully assembled the boat, and even made it out to sea—albeit in a purloined naval vessel—he was caught and returned to prison. After he was inexplicably released sometime before 1953, the couple reunited in Paris, where they married the following year, with the bride wearing a wedding dress made by the groom whose mother had taught him to sew as a child in Belgrade.

Cuff by Toza Radakovich, 1960s. Yellow and rose gold, Indian turquoise beads. Collection of Jean Radakovich.

Due to France’s restrictive visa regulations, they couldn’t remain; since Denmark was Toza’s only refugee option, they traveled to Copenhagen, a city where modern silver was being produced. There, they both learned metalsmithing, a skill Ruth had begun studying when she returned to America after the war. When Toza was allowed to apply for American citizenship, they relocated, first to a vibrant metalworking community in Rochester, New York, and then to Encinitas, located near the spirited San Diego craft scene.

Pin by Ruth Radakovich, 1950s. Gold, purple tourmaline. Terry Lindquist Photo, collection of Jean Radakovich.

The need to make a living precipitated their working together; they chose metal, Toza stated, since “we would need only one set of equipment.” As object makers and architectural detail designers, as well as sculptural jewelers unafraid to challenge accepted notions of form and scale, they performed comparably but independently, working side by side, and often critiquing one another’s endeavors. Tragically, Ruth died of ovarian cancer in 1975, on their twenty-first wedding anniversary; she was only fifty-four.

There are many other noteworthy couples working in jewelry today, such as Germans Norman Weber and Christiane Förster, Georg Dobler and Margit Jäschke, and Bettina Dittlmann and Michael Jank; Italians Annamaria Zanella and Renzo Pasquale; Israel-born Attai Chen and his German-Iranian partner, Carina Shoshtary; and Stockholm-based Adam Grinovich and Annika Pettersson, and Beatrice Brovia and Nicolas Cheng. Brovia and Cheng, like the others, maintain separate practices, but since 2011 have collaborated on a joint project that focuses on interdisciplinary material research and craft discourse through installations, objects, and jewelry. All in all, whether by a common intellect and aesthetic sensibility, compatible theoretical bent, physical attraction, or simply the mystery of love, one fact is certain: couples who make jewelry turn each other on.

Toni Greenbaum is an art historian specializing in twentieth- and twenty-first-century jewelry and metalwork.

This article has been updated to correct two errors that appeared in our Summer print issue: the proper photograph is shown with the discussion of Sam and Carol Kramer; and the caption to the image of Gijs Bakker and Emmy van Leersum’s Clothing Suggestions has been corrected.