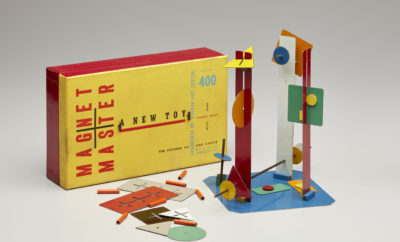

DAVID NOSANCHUK PHOTOS

DAVID NOSANCHUK PHOTOS

Design

Turning Craft Inside Out in Milan

THE EXHIBITION CALLED NEW CRAFT is housed in a vast old building known, appropriately, as the Fabbrica del Vapore, a relic of Milan’s past brought into the present. The complex was once home to a tram and rail-vehicle manufacturer and is more commonly called the “Steam Factory.” It is a perfect setting for a groundbreaking exhibition that sets up—and then disputes—the dichotomy between man and machine. Curated by Stefano Micelli, a professor at Venice International University, New Craft takes an unexpected look at the transformative role of technology in the creative realm and challenges any number of preconceptions about past, present, and future. The exhibition runs the gamut from pure design (lighting, furniture) to fashion to jewelry to bicycles, and even to pasta produced by 3-D technology. “Technology is really expanding the idea of creativity,” Micelli says. In curating this exhibition, he says he sought to show the way that new methods of production could draw on the strong heritage of design, recasting it in new materials and using new methodologies. “From a European point of view, there is plenty of existing material that can be the element of reinventing and rebuilding.” Launched in April just before Milan Design Week (Salone del Mobile), New Craft is a part of Milan’s twenty-first Triennale (ongoing through September 12), which was re-launched after a twenty-year hiatus. With the umbrella title “21st Century. Design after Design,” the Triennale encompasses twenty-two different exhibitions that range from an invigorating look at women in Italian design to a conceptual examination of the evolution of design from “Neo Prehistory” forward. The exhibitions are on view in a number of venues across the city. The curators of New Craft put out a call for work from designers under thirty-five, which means lots of entries from new and unknown names, but there are also installations from established Italian brands, such as Barilla (pasta) and Foscarini (lighting). An objective of the exhibition was to show the ways in which technology can open new paths of creativity without compromising the feeling of the hand—as evidenced in designer Monica Castiglioni’s side-by-side examples of her jewelry, with one cast by hand and the other 3-D printed.

Another 3-D-scanned and -printed piece, the Big Louie chandelier by New York designer David Nosanchuk, gained immediate fame during Milan Design Week when it was recognized for being the most-Instagrammed object on view at New Craft. The design is an extrapolation of ornament on New York City’s only Louis Sullivan building—at 65 Bleecker Street—and was commissioned in an edition of twelve by Claudia Pignatale for the Casa Italia, the Italian pavilion at this year’s Olympics in Rio de Janeiro. (Two Louies hung over the entrance to this year’s Collective Design fair in New York City as well.) Nosanchuk points out that while this piece celebrates the past, “the pendant still must be carefully made and assembled from fourteen pieces and a complex set of wiring, relying on the artisanship of a twenty-year-old 3-D printing company to become a reality, a product of the new craft.” triennale.org