Feature

The Soul of Nakashima

A new look at the master woodworker in advance of a major exhibition this fall at the Modernism Museum Mount Dora in Florida

Conoid benchThe Nakashima compound in New Hope, Pennsylvania, is now a National Historic Landmark. The Conoid Studio, built there in the late 1950s, was named for its curved and cantilevered shape that created an organic yet modern statement. The building process led Nakashima into a series of furniture designs that employed architectonic bases, including a strong reference to cantilevering. The Conoid bench, originally designed in 1960, has turned and carved spindles attached to a highly figured, freeform seat with a significant overhang on the left or right. While not produced in large quantities, the design is so striking and unusual that it has become one of Nakashima’s best known.

GEORGE NAKASHIMA was one of the great innovators of twentieth-century design, offering an approach that was like nothing that had gone before. He brought together at least two incongruous styles, traditional Japanese and American vernacular, and merged them with a modern sensibility. And in so doing, he articulated a design vocabulary that was based on the use of free edges, sapwood, knots, crotch figuring, natural flaws in wood, revealed joinery, and butterfly joints.

The tree was where everything began. Nakashima’s inventory of wood was legendary and was the wellspring of all his designs. He “saw” wood in a way that no one before him had been able to. Indeed, many thought he was crazy buying “junk” wood that they would have rejected due to its imperfections. Despite an intense and comprehensive design process, Nakashima would explain his reluctance to sign his work with the statement, “The work is not about me, it’s about the tree, it’s about nature.”

Kent Hall lamps In the same way that Wharton Esherick used light as a sculptural and artistic element in his Walnut floor lamp, Nakashima provided more atmosphere than illumination with his Kent Hall floor and table lamps, in which light is filtered through fiberglass-impregnated paper shades. The juxtaposition of a highly structured shade with a naturalistic base epitomizes the approach he took in much of his work.

Because his own words emphasize the tree, its second life as a functional object, and the concept that each board has one ideal use, it is tempting and sometimes easy to overlook the design aspect of Nakashima’s work. Rather than focus exclusively on the drama and beauty of the wood, we must also consider the heart, mind, and hand of the maker. No board cut itself, jumped on a base and made a beautiful table. Nakashima and those who worked with him toiled hard to make that happen. There was a careful design process, one that grew and developed during his lifetime. To make a piece of furniture that has a sense of simplicity and purity is not the same as making a simple one.

Minguren II table While there was always a demand for monumental dining tables, Nakashima rarely had boards that were long and wide enough to make them. At sixteen and a half feet long and almost five feet wide, this table made for a close associate of Andy Warhol is possibly the largest Nakashima ever made. Typically, for the top he cut across the crotch to reveal and intensify the figuring the tree held at its core. The table encompasses all the innovative design features in Nakashima’s “tool box”—bookmatched boards, free sap edges, crotch figuring, naturally occurring openings,and butterfly joints in a contrasting wood. Flanking the table are Conoid chairs, designed 1960.

Each piece was carefully shaped throughout: first as a mental image, then on paper, then on the boards themselves in chalk or pencil, and finally as a three-dimensional form. Even the very first decisions about how to cut the tree were design decisions that had to take into account how the grain of the tree would be most interesting and how the piece of wood might be used. “Each cut requires judgments and decisions on what the log should become,” Nakashima wrote in his book The Soul of a Tree. “As in cutting a diamond, the judgments must be precise and exact concerning thickness and direction of cut, especially through ‘figures,’ the complicated designs resulting from the tree’s grain.”

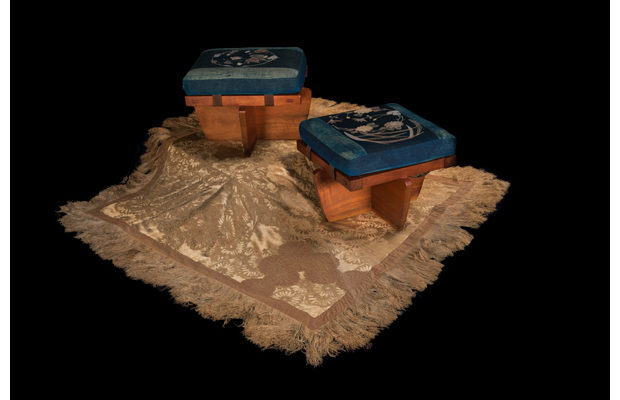

Greenrock ottomans In 1973 Nakashima received his largest and most important commission, from New York’s Governor and Mrs. Nelson Rockefeller—more than two hundred pieces for Greenrock, their Hudson River valley estate designed by Nakashima’s friend Junzo Yoshimura. The furniture included a series of small stools or ottomans that were later added to the Nakashima catalogue. The joinery reflects the traditional throughtenon method, a beautifully designed and durable joint. Nakashima saw “good joinery” as “an investment … an unseen morality.” The stools are covered with indigo dyed cotton, each stenciled with a unique batik design, that Nakashima brought back from Japan.

Nakashima developed his own oil-based finishes that enhanced the grain of the wood and brought out the qualities that made each board special. He would take customers into his wood storage area and together they would select a board. With the board in his mind’s eye, Nakashima would go back to his studio, and in five or ten minutes, draw the final piece including the sapwood, the knotholes, the cracks, the butterfly joints, the placement of the legs—all in precise detail. This drawing would then be converted to shop drawings, and the process of construction could begin.

The entire effect was so balanced that the myriad decisions made to achieve it are easy to overlook. Creating furniture that seemed natural was complex and demanded all of Nakashima’s design skills; in turn, in-depth study is required to recognize the meticulousness of the design and execution. Nakashima was very detail-oriented and closely supervised every stage of the construction process. Everything was planned, designed, drawn, and reworked before it was made. As he noted in The Soul of a Tree, “The error of a fraction of an inch can make the design fail absolutely.”

Long chair Nakashima’s designs are typically given descriptive names, as is the case with the Long chair. An exact translation of the French “chaise longue,” it is a form that is thought to have emerged in ancient Egypt. Surprisingly modern and innovative when he designed it in 1947, this 1951 version is distinguished by the horizontal bands of sea grass that are woven through the cotton webbing. Shortly thereafter, he eliminated the sea grass and began to offer the chair with a long freeform arm.

Nakashima’s devotion to design is perhaps best illustrated by using the chair as a case study. “What a personality a chair has! Chairs rest and restore the body, and should evolve from the material selected and the predetermined personal requirements which impose their restrictions on form, rather than the other way around,” Nakashima wrote, adding: “Some parts, such as spindles, are used primarily for strength, and aesthetics becomes a secondary consideration. These can be beautiful, however, and the error of just a sixteenth of an inch in the thickness of a spindle can mean the difference between an artistically pleasing chair and a failure. Function, beauty and simplicity of line are the main goals in the construction of a chair.”

International Paper room divider screen n 1980 Nakashima was commissioned to provide furniture for the president’s office and conference room of the headquarters of the International Paper Corporation, giving him a rare chance to design on a grand scale. The two screens were works of art that also served a purpose, namely to separate the large space into multiple areas. In each screen, four large American black walnut bookmatched boards are joined with contrasting rosewood butterflies that are further foregrounded by being raised above the surface. Nakashima drew the eye to natural flaws in the boards by filling them with small mirrors that he had brought back from India in the early 1970s.

When we look at Nakashima’s chairs, it is immediately apparent that most of them are influenced by American vernacular designs, most obviously the Windsor chair and the so-called captain’s chair. The Windsor influence is most notable in the Straight Back chair, the New chair, the Mira chair, the Four-Legged chair, and to a lesser extent the Conoid chair. The armchairs are a streamlined form of what we usually refer to as a captain’s chair. These traditional American designs were basic building blocks that Nakashima combined with elements of Asian vernacular design and a modernist aesthetic. For example, the New and Conoid chairs have a modernized Asian yoke back crest rail, while they still maintain a close affinity to the Windsor. The Conoid chair, now a modernist icon, also owes a debt to the 1924 and 1927 cantilevered chair designs by Heinz and Bodo Rasch. This unusual and complex combination of Eastern, Western, and modernist influences led each chair to evolve into a unique George Nakashima design.

Tea cart The use of fragile burl wood for furniture is a part of the legacy and genius of Nakashima. Burls are diseased parts of the tree, thus their growth history makes them flamboyant, yet potentially unusable: until the burl is in the process of being cut, there is no way to know whether the resulting boards will crumble or reveal a unique and spectacular figuring, as in this English oak burl tea cart and Carpathian elm burl headboard. Nakashima’s uncanny ability to “see” the wood made it possible for him to supervise the cutting of the burls so that, unimaginable to most people, they could become functional pieces of furniture.

What is especially impressive about Nakashima’s work is this quality that each piece is unique. While there are some structural and design similarities between his work and that of others working at the same time in the United States and Europe, what is overwhelmingly clear is that Nakashima’s furniture in no way depended on or was derivative of what was going on around him. In fact, while he spent two years (1928 and 1931) in Paris at the height of the art deco period and then worked under Antonin Raymond in Japan and India from 1934 to 1939, his furniture has little to do with art deco or the majority of Raymond’s modernist furniture designs. If he took anything from Raymond, he extracted what he wanted and let the rest go. This is not to say that he lived in a vacuum, but with all that was happening around him in France, India, and Japan, he found his own way —and his way was about the tree.

Odakyu cabinet Nakashima’s first show in Japan was held in 1968 at the Odakyu HALC Department Store in Tokyo, which held seven more shows of his work through 1990 and a memorial exhibition in 1991. This cabinet and floor lamp were originally designed for the 1970 Odakyu show, though the unique double-sided version of the cabinet shown here is from 1974. It is made of American black walnut and Hinoki cypress with pandanus cloth (traditionally made from the leaves of a Southeast Asian palm). The pattern—an abstraction of the hemp leaf—on the doors and on the fiberglass impregnated paper lamp shade is a midnineteenth century Japanese design called AsaNoHa. The panels were made in Japan, according to Nakashima’s directions. It is a very complex pattern in which twelve pieces of wood must intersect at particular points, and requires complicated and unusual lap joints.

A comprehensive exhibition to open in the fall at the Modernism Museum Mount Dora, presented by Main Street Leasing, will provide a wonderful opportunity to look at a large body of Nakashima designs publicly shown together for the first time. The exhibition will place Nakashima in further context by comparing and contrasting his furniture to selected pieces by Wharton Esherick and Wendell Castle. Here I discuss a number of pieces to be included, each of which reveals important elements of Nakashima’s body of work.

GEORGE NAKASHIMA was born in Spokane, Washington, in 1905 to Japanese parents who had immigrated to the United States. Educated and trained as an architect at the University of Washington, Nakashima received a master’s degree in architecture from M.I.T. in 1930. After working briefly in the United States he left for Paris, seeking the creative energy of one of the great art centers of the day. From there he traveled extensively, ending up at the home of his grandmother on a farm on the outskirts of Tokyo. In 1934 Nakashima went to work in Tokyo for the architect Antonin Raymond. He volunteered to go to Pondicherry, India, to design and direct the construction of an ashram for the spiritual leader Sri Aurobindo, whose teachings were to shape his philosophy for the rest of his career.

Nakashima returned to Japan where he met Marion Okajima, who was also born in the United States. They married and settled in Seattle, where Nakashima opened his first furniture business in 1941. His first important furniture commission, for Andre? Ligne?, brought him recognition when the Ligne? interior was published in California Arts and Architecture in 1941.

However, after the Pearl Harbor bombing, Nakashima and his family, like many other Americans of Japanese descent, were placed in an internment camp in Idaho. Here he met a Nisei woodworker, Gentauro Hikogawa, and learned the art of Japanese woodworking. Thanks to the sponsorship in 1943 of Antonin Raymond, Nakashima and his family were able to leave the camp and move to Raymond’s farm in Pennsylvania. The next year, he set up a workshop on what became the Nakashima home- stead in New Hope, Pennsylvania. He maintained and expanded his facilities in New Hope until his death in 1990, at which point he had a staff of about twelve and had produced what is estimated to be thirty-five thousand pieces.

Nakashima’s earliest designs were all custom-made to suit the particular needs of the client. In 1945 he produced a small catalogue with three chair and five table designs—so that not everything had to be custom work— followed by a larger catalogue of fourteen pieces and then another with twenty-three. In 1955 he issued his first major catalogue, presenting a standardized set of designs that could be customized, when necessary.

While innovative, this early work was relatively straightforward, for the most part lacking the free edges and other details for which he became famous. In the late 1950s, when he began to build the Conoid Studio on his property, he developed the Conoid line, adding a significant architectural component to his furniture. This series was a major leap in that the modernist structures of his furniture designs became of much greater significance. In the 1960s, while building the Minguren Museum on his property, he developed another architecturally inspired line—the Minguren series— that again shifted the basic approach of the studio. The hiring of his daughter Mira in 1970, commissions from the Nelson Rockefellers in 1973 and the International Paper Company in 1980, and his ability to source better and better woods led to some of Nakashima’s most mature and exciting work in this period.