Modern Bucket chairs for kinder MODERN, 2016. Fiberglass and steel. PHOTOS COURTESY CHEN CHEN AND KAI WILLIAMS

Modern Bucket chairs for kinder MODERN, 2016. Fiberglass and steel. PHOTOS COURTESY CHEN CHEN AND KAI WILLIAMS

Feature

The New Alchemy of Design

CHEN CHEN AND KAI WILLIAMS are designers, scientists, tinkerers, thinkers, crafts-men, manufacturers, marketers, and inventors. With so many roles to keep straight, perhaps the best word to describe them is magicians, as there always seems to be a dash of wizardry in their never-ending supply of uncommon answers to everyday design questions.

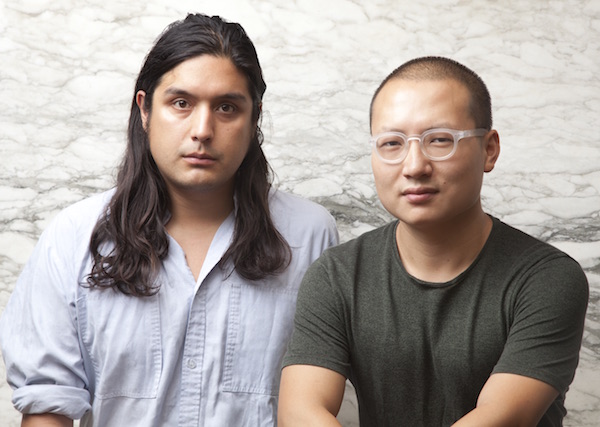

Kai Williams (left) and Chen Chen, 2016.

The duo’s shared design practice not only finds new answers, but also asks new questions. And people are paying attention—Chen and Williams have been featured in Lonny and the New York Times T Magazine, part of the next generation of innovators in the field. Both in their early thirties, they are just hitting their stride, in the sweet spot between the reckless abandon of youth and the wisdom that comes with experience.

Chen and Williams are poised for what’s next, which is likely to be found in their dust-covered studio in Sunset Park, Brooklyn. The space takes on as many roles as they do: laboratory, factory, warehouse, and command central, where they manage their own sales along with a constellation of partnerships—from small manufacturers such as Areaware and Good Thing, to a host of retail outlets and design galleries, including kinder MODERN and Patrick Parrish Gallery.

Swell vase, 2011. Glass, nylon rope, netted fabric, rubber, and expanding polyurethane foam.

Their studio is also a “closed loop,” as they put it, where scraps from one product often become the genesis of their next. As such, computers don’t necessarily offer what they need—at least not in the traditional CAD-focused sense. “We’ve always designed by just making it, rather than drawing something first,” Chen explains. Case in point: the Swell vase, which Chen began just before he and Williams started collaborating formally in 2011. Its materials read like a dare: glass, nylon rope, netted fabric, rubber, and polyurethane expanding foam. Each vase is reminiscent of a kid’s science experiment caught mid-explosion.

While experimenting with leftover netted spandex from their Swell vase, the pair unexpectedly discovered that it was the perfect vehicle for working with urethane resin. This led to their best-known product, an improbable set of caveman-like coasters that are sliced, deli-style, from what they call a “Ham Hock”—really a concoction of scrap wood, fiber, resin, and metal wrapped in spandex and soaked in more resin until solid. One part terrazzo and one part mortadella, their Cold Cut coasters quickly made their way into the press, design shops, and the 2014 exhibition NYC Makers: The MAD Biennial at the Museum of Arts and Design.

"Ham Hock” and Cold Cut coasters, 2011. Urethane resin and various other materials.

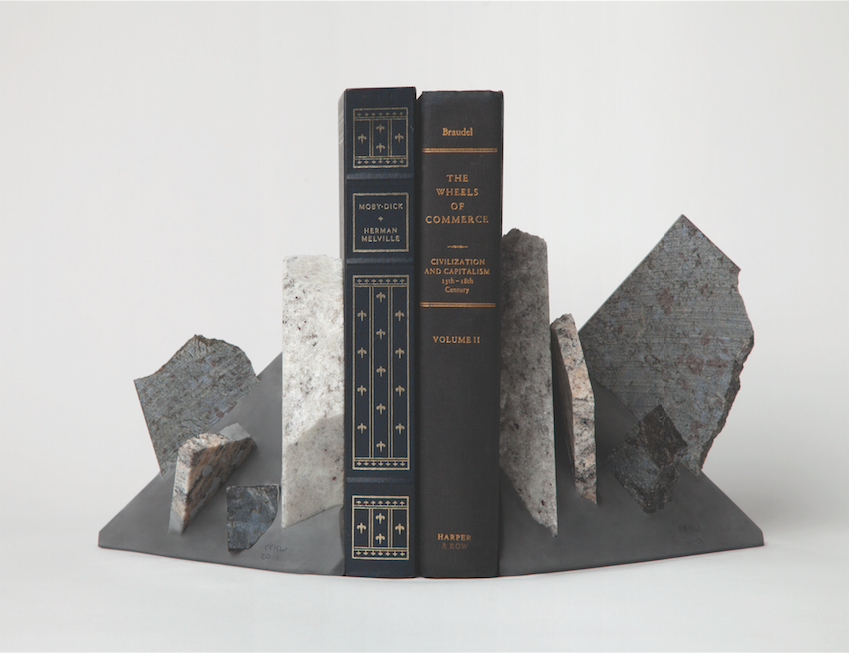

The product also pushed Chen and Williams in many new directions: Cold Cut carpets are now produced by Tai Ping, and the related Network stool was exhibited in the Miami Design District in 2012. And all those leftover resin bits continue to be repurposed into objects both large and small, from the Warp Core light to Nugget keychains sold on their website. Chen and Williams met in the industrial design program at Pratt Institute in Brooklyn and began their business in 2011, just as the grip of the great recession loosened. They had collaborated casually before then, keeping their day jobs. Williams worked with artist Tom Sachs, the low-tech revisionist, and Chen was at the New York design mecca Moss. These early antecedents have woven their way into the duo’s off-kilter approach, which finds function in the unexpected. “Nothing they are working on is ever really finished,” explains Jamie Wolfond, founder of start-up manufacturer Good Thing, whose lineup includes several of their products. Among them is their Folded Vessel, which represents one stop in a design cycle that began with Metamorphic Rock bookends and ended with mid-century-inspired fiberglass children’s chairs produced by kinder MODERN.

Directed by their experimentation, Chen and Williams were their own first client. “It wasn’t really until our fourth year that we figured out what to make to not go out of business,” Chen admits. Although they’ve carved out a business model that works across the spectrum of producers and distributors, “self-manufacturing,” as they describe it, plays a major role. Indeed, in their studio an assistant was polishing a group of Trinity incense burners, and molds labeled “Pineapple” and “Napa Cabbage” were waiting to be filled with fine cement for their Stone Fruit planters. The new alchemy extends not only to materials and forms, but also to “designing the process” itself. “There’s something very satisfying about developing your own way of making something,” Chen says. But, as Williams is quick to point out, “it’s also sort of a problem.” As they are keenly aware, “if you invented this process, how do you define it for someone else?”

Metamorphic Rock bookends, 2011. Stone shards cast in cement.

Chen and Williams’s question points to something important that’s been going on in design, especially in Brooklyn—the rise of the independent designer. As Chad Phillips, director of merchandise at the Brooklyn Museum points out, technology has a lot to do with it. It offers an Instagram-ready marketplace, same-day pick-up for 3-D-printed prototypes, and easy access to everything that the Internet affords—from technical information to the essential two-way connection with the worldwide design community.

Chen and Williams are in good company in Brooklyn—Misha Kahn, Katie Stout, Ladies & Gentlemen Studio, fellow Pratt grads Gregory Buntain and Ian Collings of Fort Standard, and the studio of Vonnegut/Kraft, which happens to be just down the hall, are among the countless designers and makers based in the borough. The flourishing of “Brooklyn design” is well documented, charted not only in industry-specific media like Sight Unseen but also in the mainstream—from Martha Stewart Living to the Wall Street Journal. So much so, in fact, that while the community is vital—sharing ideas and resources—its “brandification” sometimes teeters at the precipice of cliché.

Nugget keychains, 2013. Urethane resin and various other materials dipped in epoxy resin, including repurposed resin scraps from Cold Cut coasters and other products.

However, given Brooklyn’s international reach, one wonders what design history will have to say of this period when designers like Chen and Williams are teaching the factory new ways of making—or bypassing it altogether. Will this be seen as a moment? A school? A movement?

For now, Chen and Williams are thinking in the present tense. No longer upstarts, they toggle between the business of design and holding on to the experimentalism that has gotten them to where they are. “It’s a major juggle,” Williams says, adding wryly, “we probably have more materials than anyone really should in their shop.”