In Praise of Epicurus chair by Ettore Sottsass, Renzo Brugola for Blum Helman, 1987. COURTESY OF WRIGHT VIA POWERHOUSE BOOKS

In Praise of Epicurus chair by Ettore Sottsass, Renzo Brugola for Blum Helman, 1987. COURTESY OF WRIGHT VIA POWERHOUSE BOOKS

Design

Talking Shop

Patrick Parrish in his Manhattan gallery. Scott Newman Photo, Courtesy of Powerhouse Books.

PART ART AND DESIGN WORLD BAEDEKER, part memoir, Patrick Parrish’s The Hunt (powerHouse Books) offers essential guidance on topics such as gallery etiquette and self-education, along with anecdotes of his path from art student and design enthusiast, to picker, to an established New York dealer. MODERN’s Gregory Cerio visited Parrish in his eponymous storefront on Lispenard Street in downtown Manhattan to discuss the book:

Gregory Cerio/MODERN MAGAZINE: I like the tone of voice you used—it’s authoritative, but friendly and confiding.

Patrick Parrish: An editor could really have cleaned up what I wrote, but we wanted it to feel like I was just talking to the reader. So we kept my kind of slight dyslexia in there, too.

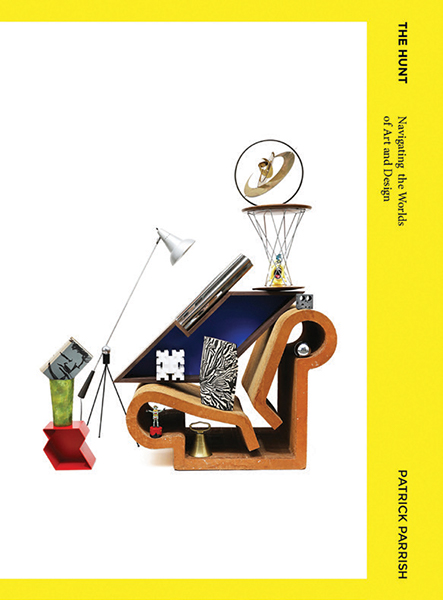

The Hunt: Navigating the Worlds of Art and Design By Patrick Parrish (powerHouse Books, $19.95)

GC: Was the book prompted by seeing people who seemed intimidated by the idea of buying art? Who were unsure how they should even act in a gallery?

PP: A little bit. Some of the behavior we see is kind of amazing. We’re pretty open here. People ask, “Can I bring my dog in?” Yes. “Can I bring this drink in?” Yes. “Can I touch that?” Yes. But the ones who come in just blabbing on their cell phones and they never even look at you—that’s crazy. But another reason for the book is that…well, I always thought I’d be a teacher. I like filling people in; telling them about things that I like that they might like; showing them things that maybe they’ve never heard of or seen before.

Greene Street chair by Gaetano Pesce for Vitra, 1984. Courtesy of Wright via Powerhouse Books.

GC: Compared to those of other dealers, was your career arc a strange one or was it typical?

PP: I think it’s fairly typical. There are a lot of failed artists in the antiques world; it’s filled with characters—people who wanted to do something else and couldn’t, but had an interesting eye. I fought it for a long time. I wanted to be a fine artist, a photographer. Dealing antiques was just going to be a way to support making art. But I gave into it—that was a long time ago—and I’ve enjoyed this work much more ever since.

GC: I met you more than fifteen years ago when you were still a picker, a few years before you opened a gallery. How have you seen the business change in that time?

PP: There are very, very few of us left who are actually on the street, with galleries you can walk into during normal business hours. In New York, the real estate is just too expensive. You can’t afford to have a gallery in a prominent spot like Lafayette Street anymore. And in those areas where you can afford the rent you don’t get the customers who will buy a $3,500 Gilbert Rohde clock. It’s sad, but I’m holding on as long as I can.

Mezzadro stool by Achille and Pier Giacomo Castiglioni for Zanotta, 1957. Courtesy of Wright via Powerhouse Books.

GC: It’s also rare today to see a store dedicated to one design style or period.

PP: You have to do more than one thing now—you sell both fine art and design, both contemporary and vintage design. My contemporary business is quickly overtaking my vintage business. The vintage is harder and harder to find, there’s so much competition. There’s competition for the contemporary, too, but once you establish a relationship with an artist they tend to stick with you. But the days of going into a store that carries only, say, American art deco—those days are long gone.

GC: Did outfits such as Design Within Reach take the cachet away from mid-century pieces?

PP: When Herman Miller reissued the Eames surfboard–shaped coffee table, dealers said: “Oh no, we’ll never be able to sell another surfboard table again!” But in my experience the reissue had the opposite effect. It introduced many people to the design, and among them were the ones who said: “That’s cool, but I want the old one.” Anyone who understood, who got it, didn’t want the thing that looked brand new.

Up M1002 and Hiraqla #3 by Richard Pettibone, 1970. Courtesy of Wright via Powerhouse Books.

GC: What’s your take on design-as-art? Is it not enough to be simply a furniture designer?

PP: I never say “designer,” I usually call them “artists.” Even people who are making a coffee table, I generally call them artists because they often come out of the art world and for whatever reason are making functional objects. There are some whose attitude is “I’ve made this limited-edition chair and it’s art, and I’m going to sell it to people who collect art”—and a few have been successful. But when the work becomes so forced and the prices get so high— then it becomes problematic for me.

Copper armchair by Donald Judd for Lehni, 1984. Courtesy of Wright via Powerhouse Books.

GC: What about limited editions?

PP: There are some collectors who want to know that their coffee table is one of only ten. But the problem is that the edition consists of the ten tables exactly like that. If you make the same table but five inches wider, technically it’s not part of the edition. There’s always a way to get around an edition. So it’s kind of useless. Editions are more for that certain customer, and for dealers they’re a way to inflate the price. But when an artist makes something cool, I’d think it’s best to get it out into the world as much as you can, whether you sell ten or whether you sell a thousand.

GC: The book has the obligatory list of which design markets are hot, on the rise, cold, or just dead—like arts and crafts, which is a shame so much of it is beautiful.

PP: Yeah, I don’t see arts and crafts coming back anytime soon. Right now, weird and ugly is in.

GC: I do see a lot of things that make me scratch my head and wonder why.

Untitled (paper mask) by Irving Harper, c. 1960s. Courtesy of Wright via Powerhouse Books.

PP: There are things being made for a very specific kind of person who will spend upwards of $35,000 on a little fur-and-bronze animal. There’s a certain crowd that wants that, and it’s no different from the one-hundredth of one percent of art collectors who have to have a Jeff Koons. But it’s interesting how carefully cultivated that market is, how galleries have calculated what’s just the right amount of outrageousness. I don’t have a problem with it. Look, you’ve got to pay the bills. But I’m not there yet with the artists I work with.

GC: Speaking of making markets, you made the market for the work of Carl Auböck, the early twentieth–century Viennese designer of brass desk accessories, barware, and such.

PP: Auböck’s work is kind of the perfect thing to collect. Because he made somewhere between forty-five hundred and six thousand different designs, there’s always something new to find. It’s small, it’s well made, it feels good in your hand. His materials—brass, leather, horn, bamboo—are humble, but they’re warm and beautiful. Once we figured out what it was—this was in the days before the Internet—Auböck’s work wasn’t very hard to promote.

GC: There is a lot more information now, with the Internet. But don’t you find it frustrating that so much of it is bad information? The same myths and mistakes are repeated over and over.

Console by Ico and Luisa Parisi for Singer & Sons, c. 1952. Courtesy of Wright via Powerhouse Books.

PP: Part of the reason I once wrote a blog, called Mondoblogo—I focus on Instagram now—was to debunk some of those design myths. For example, I wrote about a table that’s constantly attributed to Jean Royère. It’s sold in the United States as Royère, it’s sold in France as Royère, everyone wants it to be Jean Royère—but it’s an American aquarium stand. It should cost $200 but it’s sold for thousands of dollars. And the attribution goes on and on. When it comes to facts about art and design I’m a stickler.

GC: Last question. Was there anything you accidentally left out of the book? Something you didn’t remember you wanted to write until it was too late and the pages had gone to the printer?

PP: Yes. Whenever you do a Google image search, always include a minus sign and Pinterest in the search terms. [Like so: -pinterest —Ed.] Pinterest is the bane of my research existence. It clutters up every search.