Architecture

Summer of Design: A Semi-Centennial and a Special Sale

LOOKING AT LE CORBUSIER IN PARIS

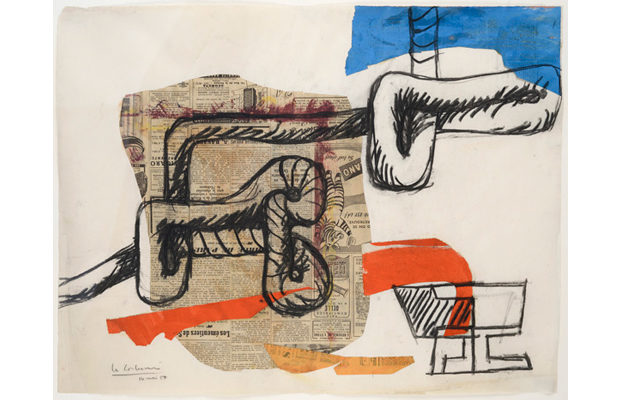

Images courtesy of Centre Pompidou/©FLC, ADAGP, 2015

Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, aka Le Corbusier, changed the face of twentieth-century architecture and urban planning. To mark the fiftieth anniversary of his death in 1965 the Centre Pompidou in Paris has mounted a retrospective of his work, on view through August 3. In parallel, two Left Bank Parisian art galleries, Eric Mouchet and Zlotowski, are putting on commemorative shows of their own, running through, respectively, June 13 and July 25.

In three hundred works the Pompidou exhibition reveals the complexity and richness of Le Corbusier’s contribution to the development of a modernist, humanist intellectual and aesthetic framework for the reconstruction of a world shattered by the Great War. The exhibition fleshes out the two-dimensional image of Le Corbusier the architectural theorist to show an artist of multiple talents. A painter, draftsman, sculptor, writer, and photographer, he was a friend of the cubist painters Fernand Léger and Amédée Ozenfant and, in the 1920s, the founder with Ozenfant of a post-cubist art movement that they named “Purism.” “Throughout his life he painted every morning,” says Frédéric Migayrou, head of the Pompidou’s architecture department and chair of the Bartlett School of Architecture at University College, London, who curated the show: “He dedicated half his life to painting.”

Purism dismissed cubism as merely decorative and proposed a rigorously ordered construct of the natural world, with the human figure at the summit. One of the strengths of the Pompidou show is its decryption of Le Corbusier’s design philosophy, in which his conception of the human body and its relationship to perceived space is the key to harmonious proportion. That approach culminated in his definition, between 1943 and 1948, of a universal architectural scale that he called “Modulor.” Based like Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian man on the proportions of the human figure, the Modulor in final form adopted a base unit of 1.83 meters, being the height of the ideal man, modulated to produce subordinate units using the golden ratio and Fibonacci numbers.

If that sounds abstrusely mathematical, the choice of the base unit was quirkily human. Initially proposed at 1.75 meters, the height of the average Frenchman (Le Corbusier, born Swiss, adopted French nationality in 1930), it grew to the metric equivalent of six feet because, as Le Corbusier later explained, “in English detective novels, the good-looking men, such as policemen, are always six feet tall.”

Courtesy of Galerie Eric Mouchet and Galerie Zlotowski/©FLC, ADAGP, 2015

While the Pompidou aims for a full 360-degree view of Le Corbusier’s artistic and architectural career, Eric Mouchet and Zlotowski have focused on his decorative work. The Galerie Zlotowski concentrates primarily on Le Corbusier’s collage works, while Mouchet has brought together thirty pieces in a range of mediums, including gouache, pastel, pencil, and charcoal on paper; enameling on sheet metal; wood and metal sculptures; oils; and collages.

Museum-quality paintings on show include a 1956 Taureau (Bull) that could easily be taken for a Picasso— though Le Corbusier himself might not have seen that as a compliment, for he told the journalist and author Taya Zinkin in 1952 that he was “a much greater artist than Picasso; a much better draftsman.”

centrepompidou.fr/en galeriezlotowski.fr