Design

Rocker of Ages

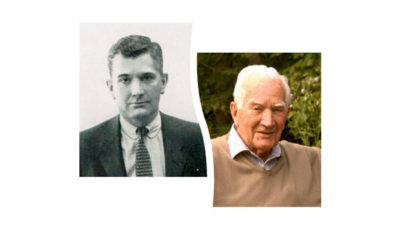

Catering to women, this 1949 magazine advertisement presents the lifestyle of ease afforded by the Barwa lounge.

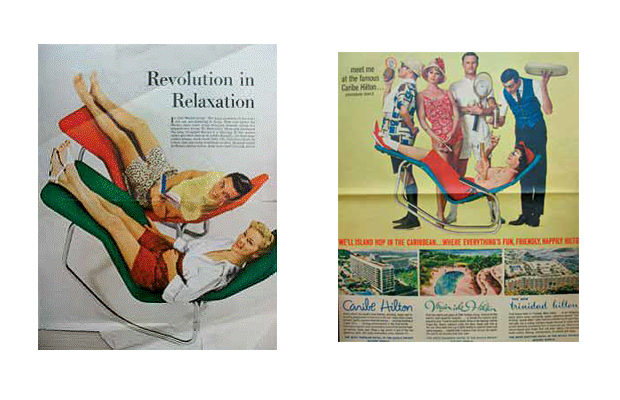

Syncing the Barwa lounge with leisure, the chair was featured in a 1960s advertisement for Hilton Hotels in the Caribbean.

ROCKER OF AGES

THE DAUGHTER OF ONE OF THE VAUNTED BARWA CHAIR’S DESIGNERS LOOKS BACK AT ITS HISTORY.

Every now and then, the Barwa pops up in an auction catalogue for midcentury modern furnishings.It’s the simplest of chaise lounges, a quirkily shaped aluminum tube frame, within a taut canvas slipcover,angled for easy feet-over-head reclining. Yet behind its modest, if ingenious, design is a tale of storied roots and fleeting fame, which still has much to say about the challenges of independent furniture making today. Being a former design journalist, I should know, as the Barwa was designed by my father Edgar Bartolucci and Jack Waldheim, who was a classmate at Chicago’s School of Design in the early 1940s.

The school was run by the Hungarian-born artist and designer László Moholy-Nagy, a former Bauhaus professor who fled the Third Reich in 1933. One of the most influential teachers at what may have been the most influential design school of the modern era, Moholy, as his students called him, preached of the creative frontier offered by the fusion of art and industry, which he saw as the promise of the twentieth century. Technologies like photography, he believed, would eventually engender new ways of seeing—and thinking. “Design,” Moholy said, “is not a profession, it’s an attitude. [It’s] thinking in complex relationships.”

Such a vision along with a conviction that design could improve mankind’s lot made for a heady atmosphere among the ten or so students at the School of Design, who dressed in dungarees like workers, and boldly experimented with weaving, welding, woodworking, plastics, and photography in their classroom in an old bakery on Chicago’s Ontario Street. Although the war was still raging when my father and Waldheim finished their studies at the end of 1942, they were already prepared to design a better future for the new world everyone hoped was soon to come.

The pair immediately got a gig as designers from a Grand Rapids furniture maker with a showroom at the Chicago Furniture Mart. The pay was $35 a week, excellent money for young men just out of school—a portent they thought of the brilliant careers that lay ahead. The company’s owner set them up in an office with a couple of drafting tables and a six-foot-high pile of drawing pads. Their assignment, it turned out, was not to rethink furniture, as would have been in keeping with the Bauhaus ethos, but to come up with every variation of a wood radio console they could think of. “We drew big cabinets, wall cabinets, cabinets with clocks, ridiculous things,” my father recalls. “We had gone through about three feet of pads, when the owner finally came back days later with two young women and reviewed our designs. He circled the ones he liked, crossed others out, told the women to combine elements from various versions, and sent them off to render them. After just two weeks, we were out of the design business!”

Dejected, and a bit demoralized that they had already been reduced to product stylists, they weren’t quite sure what to do next. Happily, a chance encounter led to a meeting with the creative director of the Container Corporation of America. A forward looking industrial giant that manufactured corrugated boxes, the company was run by Walter Paepcke, who happened to be the chief American patron of Moholy and his School of Design. Waldheim and my father were commissioned to create a number of interior architecture projects, most notably a design lab where the company could show off the superiority of its package designs to clients.

For one of the design lab vignettes, the young men used a reclining lounge chair fashioned out of plywood and nylon webbing, which Waldheim had made for a school project. Drawing on Corbu’s iconic adjustable chaise lounge and some plywood and webbing furniture by Marcel Breuer, he had conceived a streamlined version of the Thonet lounge chair. Seeing it in a new context, though, got them thinking: this could be the chair of the future.

In their spare time, the two young men fiddled with the design. After the war ended in 1945, they made a few prototypes of out of steel. But the recliner’s shape remained unwieldy; and it was too big and heavy to efficiently ship. They decided to design a knockdown version and experimented with copper piping, before settling on aluminum tubing, which was strong but lightweight and malleable, and could be affordably priced to sell widely.

Alcoa, meantime, was looking for things to manufacture out of aluminum, and a company salesman gave them enough tubing to make six different versions of the chair. With this material, they ultimately fashioned a final prototype of just the right aluminum density. But by then, Alcoa had lost interest in manufacturing it. The pair would have to buy the aluminum themselves. But they had no money, and no track record for a bank loan. (The credit card had yet to be invented.) So they told Alcoa if the company advanced them enough aluminum to make a thousand chairs, they would pay six percent interest on the cost every month until their debt was paid. They made the same deal with the fabric wholesaler that provided the canvas with which they now wanted to cover the chairs. And so in 1947, they began production on a hundred chairs at a time. Design, they were discovering, was indeed about thinking in complex relationships.

Unlike my father, Jack Waldheim was not only a talented designer, but also a consummate publicist. Without a hint of embarrassment, he wrote press releases promoting the chair as the “world famous Barwa” and claimed that the name—an acronym of his and my father’s surnames—actually referred to the eponymous Himalayan mountain because reclining in the chair produced the same feeling of exalted serenity as contemplating the famous peak. Bunkum, but it worked. Decorator showrooms throughout the country were soon selling the chairs.

Within a year, the Barwa was being extolled in national magazines like Life, Look, and The Saturday Evening Post. The benefits of reclining with feet elevated gave the Barwa a salubrious aura at a moment when Americans were becoming increasingly health conscious. Hospitals ordered the chair for maternity wings to aid the sore, swollen feet of the women giving birth to the postwar baby boom.

Nowhere did the Barwa sell better than in Palm Springs where contemporary houses with casual living spaces were sprouting and furnishings that moved from living room to patio were all the rage. Yet my father and Waldheim felt frustrated because they couldn’t sell the Barwa to department stores, because they couldn’t get the investment upfront to manufacture the chair in large quantities.