Architecture

Preservation Pulpit: The Heart of Minneapolis

Keri pickett photo, courtesy of the cultural landscape foundation.

The sad photo of Peavey Plaza—showing a misshapen puddle in the center of a concrete terrace beneath a gray sky—published on Minneapolis’s Star Tribune website on July 6 is such a poor representation of M. Paul Friedberg’s groundbreaking work that it is almost dishonest. And when you compare it with the rendering of the new plaza proposed to replace this important modernist landscape that appears on the same page, it is as close as you can get to a smear campaign.

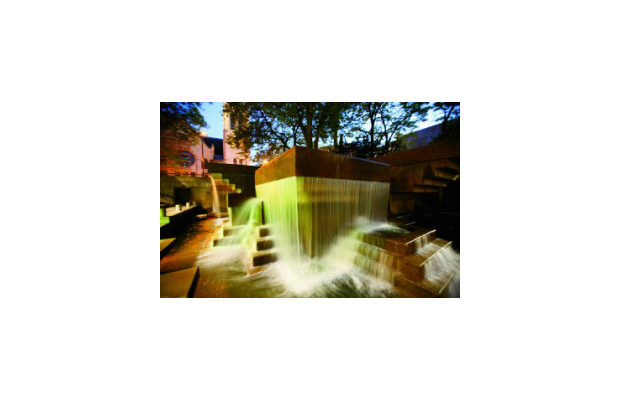

The truth is, there is no single way to understand Peavey Plaza, the downtown cultural resource that has served as a gathering place and resting spot for decades. Mary Tyler Moore spun around in the plaza and threw her blue hat into the air there when she filmed her TV show’s famous opener. Countless wintertime skaters have glided across its ice rink (search Flickr for heartwarming pictures as proof). Erin Berg, a field representative for the Preservation Alliance of Minnesota, visited Peavey between music lessons when she was a child, and her own children took excursions there during daycare. Lunch at Peavey Plaza was a weekday tradition for architect Paul Hannemann for years. The city’s former arts commissioner and current director for the Stevens Square Center for the Arts, Trish Brock, who lives seven blocks away, remembers when she fell in love with the plaza. “I had been living in London and returned to Minneapolis in 1981. Walking downtown, I came upon this amazing public space—an integral part of the streetscape that could not possibly be overlooked. The plaza had a unique geometric concrete fountain graced by honey locust trees that turn an intense yellow in the fall. The amount of water that flows and moves and stands in the park is what makes it so incredible,” she says.

The plaza welcomed Brock home and eased her transition, as leaving behind Europe’s rich arts heritage had not been easy. The indelible memory of this first view stayed with her, and motivated her to launch a Save Peavey Plaza campaign when she learned of the threat to this historically significant modern park plaza. Brock attended the public meeting in early 2011 where architect Tom Oslund first opened discussions about making changes to the plaza. “Following that meeting, I met several times with my council member, Robert Lilligren, asking about the city’s plan for the plaza, but he told me he didn’t know anything about it,” she says. “I wrote to the mayor, the council members, the city’s cultural coordinator to express my concern, but it was all falling on deaf ears.” Since then, Brock has created a Save Peavey Plaza page on Facebook and has been staging an individual protest by standing in the plaza holding a “Save Peavey Plaza” sign day in and day out.

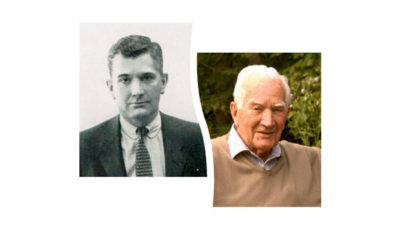

Brock’s personal devotion and connection to the plaza are matched, if not upstaged, by Peavey’s importance in the American canon of modern landscape architecture. Designed by Friedberg in 1973, the two-acre plaza meets the need for a public gathering space in the Nicollet Mall area. Its cascading fountains, sunken amphitheater, lawn terraces, and sculpture make it a true “park plaza”—a mix of hardscape and green space rather than all one or the other—the first example of this landscape genre to appear in the United States. So when Oslund was quoted in the local Star Tribune newspaper last year as saying that his new design demonstrates “a similar spatial understanding”, he revealed how little he actually understands of Peavey Plaza’s value. Meanwhile, Friedberg, who turned eighty-one this year, has already developed a concept that retains all of the plaza’s best features while also updating elements that are essential today, such as making the park handicap-accessible. Defying logic, the city has refused to consider Friedberg’s updates. One might think this is due to a budget problem, but in fact Friedberg’s concept would cost less than Oslund’s to install. The city also ignored the Minneapolis Heritage Preservation Commission 8-1 vote to deny demolition of the plaza.

Thanks to a provision in the Minnesota Environmental Rights Act that protects natural and historic resources for future generations, the Cultural Landscape Foundation—in conjunction with the Preservation Alliance of Minnesota—filed a lawsuit this summer to prevent the destruction of Peavey Plaza. The Cultural Landscape Foundation, which has been drawing attention to threatened cultural landscapes both modern and otherwise since 1998, has never filed suit before, suggesting that a new level of activism is worthwhile in this case.

mnpreservation.org and tclf.org