Uncategorized

Painting in Impasta

MAC AND CHEESE, that longtime staple of the American diet, is something I wouldn’t touch even in preschool. It was the second half of the dish, the cheese, that I hated. Pasta was another story, and not just because it tasted good. You could turn macaroni into earrings. And spaghetti! You could twirl it around a fork and make disgusting noises as you sucked it into your mouth. Playing with your food was invariably best when the food was pasta.

But for American children, pasta is also a vital art supply. What self-respecting parent hasn’t displayed an offspring’s pasta art—often macaroni, hold the cheese—on the refrigerator? Dried pasta, typically a mix of flour, salt, eggs, and water, pasted onto paper. The simple appeal of pasta matches that of the creations.

Italian children don’t do this, and it’s a shame: pasta is their heritage. (Though the exact origins of pasta are lost in le notte dei tempi—“the mists of time” sounds so much better in Italian— the country can definitely lay claim to having invented tomato sauce in the seventeenth century.) But great art is also their heritage, which leads me to wonder: what if some of the Old Masters had occasionally substituted pasta for paint? Consider The Birth of Venus, for instance: for the goddess’s titian (speaking of Italian artists) hair, Botticelli could have used a combination of tomato-based linguine and fusilli, though he’d have had to straighten out the corkscrew noodles a bit. And Venus could have arisen from conchiglie, the shell-shaped pasta. Giotto’s Vision of the Chariot of Fire? Rotelle would have been perfect for the wheels.

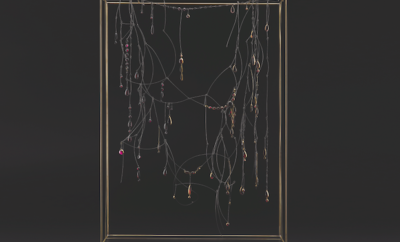

Since pasta knows no international boundaries, there’s no need to limit the field to Italians. In 2008 infrared technology revealed a painting underneath Picasso’s The Blue Room: a portrait of a man wearing a bow tie. Perhaps if the artist had used a bit of farfalle for the tie, he’d have kept the canvas, and done The Blue Room on another. We’ll never know. Van Gogh, who made several self-portraits, could have employed orecchiette for various depictions of his legendary ear. He could have upped the tactile interest of his Cafe Terrace at Night by using pastina for stars and spaghetti nero di seppia—pasta black with squid ink—for the table legs and shutters. And what about Jackson Pollock? He’d probably have skipped the pasta, but oh, what he might have achieved by dribbling with sauce. In pasta art, the medium really can be the message.

I’ve just been looking at a great many Renaissance depictions of angels, and must stop. I keep wishing their heads were crowned with angel hair pasta.