COURTESY RICH BRILLIANT WILLING

COURTESY RICH BRILLIANT WILLING

Design

Old Craft, New Form

“We can’t say ‘brand-new’ when we talk about chairs, but lighting has truly become a brand-new category,” says David Alhadeff, founder of The Future Perfect, the New York and San Francisco design store with Brooklyn roots. Alhadeff credits this change to technologies such as LEDs and the newfound nimbleness of design firms that take ownership of production. “Customers are now buying lighting as sculptures, because for the most part, the architecture does most of the lighting for them,” he says. “No one says ‘I need a fixture to light my dining room’ anymore.”

And while not all lighting firms fall into the sculpture camp, Alhadeff hits on what lighting designers are celebrating and debating, with some designers choosing to create sculpture and others looking to incorporate their work into the “systems” of architecture and still others choosing to do both. “We sort of straddle those two,” says Theo Richardson, of Rich Brilliant Willing (RBW). “In our firm we say that architects and designers are looking for statements or staples.”

Palindrome 6, manufactured by Rich Brilliant Willing. Courtesy Rich Brilliant Willing

LEDs, OLEDs, and fiber optics allow architects to incorporate lighting into building materials in a manner that was heretofore limited to tracks, recessed cans, and fluorescent tubes. But Richardson notes that tighter incorporation requires lighting to be considered at the very start of the design process, something that many firms don’t have a full understanding of yet. Still, such integration doesn’t preclude the need for the chandelier. RBW’s Palindrome designs “respond” to architecture with malleable arms that adapt to a space.

Perhaps the quintessential sculptural firm might be Roll & Hill, a collaborator with several independent design firms. Started in 2010 by Jason Miller, Roll & Hill was an antidote to the sleek and minimal Italian products that had been the mainstay of lighting design for much of the recent past. “When I was putting the company together the three biggest Italian companies produced roughly the same thing,” he says. “We create fixtures that don’t just light the space but do something else physically or emotionally.”

Knotty Bubbles chandelier by Lindsey Adelman, 2010. Courtesy Roll & Hill

Indeed, Roll & Hill’s collections are “meant to feel good and feel familiar,” with designs such as Philippe Malouin’s brutalist-inspired Gridlock pendant, an ensemble of tiny brass sticks that step out from the light source; or Bec Brittain’s Maxhedron, a quartzlike reflection of transparent mirrors filled with celestial halogens; or Miller’s Modo chandelier, inspired by ready-made parts found at low-end lighting stores. Buyers already consider some of the designs, such as Lindsey Adelman’s 2010 Knotty Bubble series, classics. That series utilizes ropes that would seem to be at home on a seaside dock. But with the audience adapting to the technology, familiar touchstones may no longer be necessary. “As people get more comfortable with this kind of lighting they branch further away from the history,” Miller says. “Decorative lighting will eventually morph into its own thing apart from historical references.”

Maxhedron by Bec Brittain, 2012. Courtesy Roll & Hill

After designing more than eighteen hundred lighting products, Robert Sonneman, the seventy-three-year-old lighting designer known as “Lighting’s Modern Master,” couldn’t agree more. He’s now more interested in architectural incorporation than in creating stand-alone fixtures. He says changes in the industry are “evolutionary rather than revolutionary,” but he allows that the last six years have been “pretty dramatic.” Five years ago, 10 percent of his firm’s products were LEDs; the following year they were 30 percent; now they are nearly 100 percent. “From the mid-century to the postmodern period we were designing appliances; that’s what lighting was,” he explains. “More and more, lighting is becoming a systems-based discipline that is a part of the original vision of the architecture.” He says that the LED’s minimal scale also allows for a broad expanse of modular systems, like his Suspenders series that can ramble across a grand space. “The sculptural vernacular has changed—the keyword now is integration,” he says.

An installation shot of the Suspenders series designed by Richard Sonneman, 2016, manufactured by Sonneman. Courtesy Sonneman

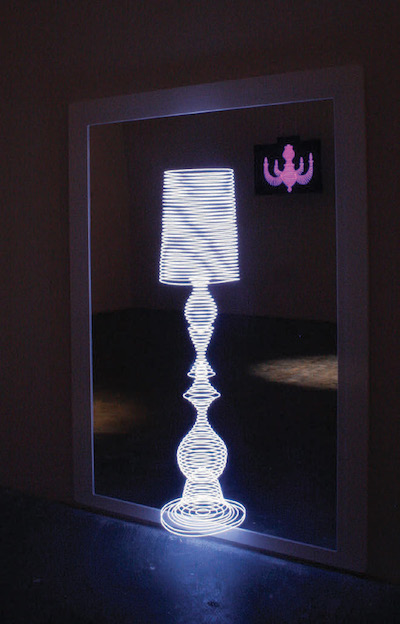

And yet technology has also allowed lighting to become high art, as in the work of David Nosanchuk. Nosanchuk’s use of 3-D printing and LEDs has allowed him to incorporate lighting into the very materials he’s working with. “The technology has freed designs from being centered on the light source,” he notes. Nosanchuk concurs with Sonneman, saying that the modernists pulled the light sources away from the architecture, making a distinction between the building and the lighting source. “At St. Peter’s in Rome the design and architecture are one,” he says. “Modernism is where they pulled the fixture away from the wall to sell.” But, Nosanchuk says, the merging of light and architecture doesn’t negate the need for sculpture, rather it’s a moment for it to shine. “People need art and stories and narratives, they need to be engaged with time and place,” he says. “Light is more than a delivery device.” For artist Marcus Tremonto of Marcus Tremonto Studio, it’s the divorce from light as delivery device that makes for great art. “When looking at James Turrell and Dan Flavin, it’s when you remove the traditional concept of purposefulness that you enter a conversation with the viewer,” he says. “If you can give them something that is unique it becomes something that they think of as their own, and that’s the kind of emotion that stirs.”

Production shot of a chandelier from the Stickbulb series by Russel Greenberg and Christopher Beardsley, 2012. Courtesy Rux Design

Nosanchuk says today’s designers are much more comfortable using technology to reference the familiar, as he does in Butterfly Asteroid, where a multitude of butterflies rest atop a massive asteroid glowing from within. The butterfly wings are made from quarter-sawn steamed beech veneer. Laser engraving on both sides, starting at a twenty-thousandth of an inch thick, reduces the veneer “to the state of translucency.” The butterflies’ solid bronze bodies anchor the piece, while the to-scale model of the Itokawa asteroid in fiberglass renders a “glowing cosmic moon.”

View of the Butterfly Asteroid by David Nosanchuk, 2016.

Nosanchuk’s butterflies nod to nature, but in a referential way they also acknowledge a vulnerable planet. A few designers are incorporating earth concerns in a more literal fashion, as is the case with Russell Greenberg and Christopher Beardsley’s Stickbulb series, in which linear strips of LED lights make up a modular system with solid wood in maple, walnut, oak, Heart Pine and Water Tower Redwood sourced from demolished buildings. Greenberg and Beardsley have built up a network of local vendors who share their values. The two say that LEDs have freed them to treat light as just another material. “The light and wood become one monolithic story, but light is just one thing we were working with,” Beardsley says. The two describe the system as a cross between Buckminster Fuller and Tinkertoys.

Closer view of the Butterfly Asteroid by David Nosanchuk, 2016.

With the overall minimalist aesthetic nailed down, the duo concentrates primarily on improving components and refining sourcing so that they and their clients know exactly where the wood is coming from. “Modular architectural systems feel like a dry connotation, but it’s rigorous to really tease out where the wood comes from, down to the address of a demolished building,” Greenberg explains. “But there are these rich histories that make people aware of where their product comes from. It may sound like nostalgia, but it’s very modern.”

It’s a value shared by designers at Graypants, whose cardboard light fixtures were initially sourced from boxes found in alleyways near their Seattle studio. But with growth comes practicality and unexpected sources, such as nearby car dealerships, which had a glut of packaging cardboard for bumpers and the like. In the Scraplight white series, the concept evolved into pure white corrugated cardboard globes cut on a Swiss-made Zünd cutting machine. But the popularity of the lamps has challenged the firm. “As it gets bigger and bigger we have to ask how do we maintain that ethos,” says Jonathan Juncker, who runs the firm with partner Seth Grizzle. “We have yet to let it go, but it’s a fun challenge.”

Installation view showing the Scraplights series, designed and manufactured by Graypants. Courtesy Graypants

The well-being of the earth and the well-being of its inhabitants go hand-in-hand, so it comes as no surprise that when designers are asked about the future of the industry they point to the relationship between good health and good light. With more academic studies correlating lighting to productivity and happiness, the natural progression of the LED technology is to create designs that adjust color and brightness over the course of the day and the course of the year. Designers are talking about a kinetic medium that interacts with users and reacts to the weather. They foresee a system of lights that come on earlier in the wintertime, dim ever so slowly before bedtime, and react to our circadian rhythm. Some LED manufacturers, such as Lighting Science, are in the thick of developing the “biology of lighting” and are pointing toward consumer bulbs that mix a spectrum of blue light with the right color temperature to create healthy environments.

S1 lamp, with Rango hanging light, both by Marcus Tremonto, 2007, manufactured by Marcus Tremonto Studio. Courtesy Marcus Tremento

The love affair between designers and LEDs can’t be understated, but challenges persist. Miller points out that LEDs are still rather directional, whereas an old-school incandescent bulb gives off a hard-to-beat 360-degree light. And while all the bells and whistles of morphing color temperature sound exciting, it can also come off as a “laser light show,” he says. But his firm, like many of the firms mentioned here, are working toward replacing the tried-and-true filament bulb. “They’re very inefficient,” Miller says bluntly. And when asked if he’d miss the warmth and charm of the filament, even just a little, he answers swiftly: “Nope.”