Design

Man of Distinction

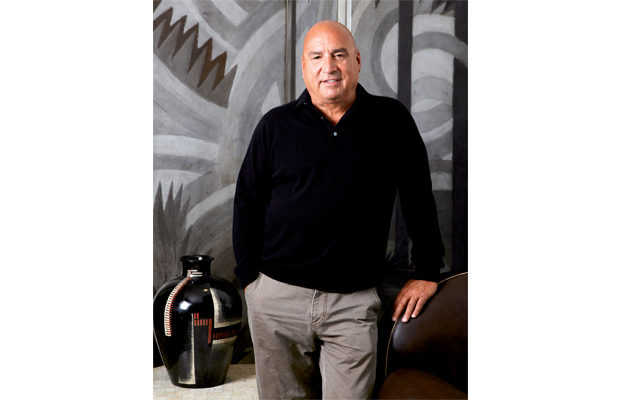

DeLorenzo in his Madison Avenue gallery.

A Conversation with dealer Anthony DeLorenzo ,who, starting from modest roots in New York ,is now one of the premier tastemakers in art deco and modern design.

Interview by Peter M. Brant

Thirty years in the business, New Yorker Anthony DeLorenzo (known to all as “Tony”) has become one of the pre-eminent dealers in twentieth-century design—most particularly pieces from the art deco period. In that field he is regarded as the top gallery owner in New York, if not the entire United States. His gruff, plain-spoken demeanor masks a high degree of erudition, but DeLorenzo credits his business success to an almost mystical power to forecast what the “next big thing” will be in the market. Normally reticent with the media, DeLorenzo sat down with Peter M. Brant—his friend, the owner of this magazine, as well as Interview, Art in America, and The Magazine ANTIQUES, and a collector of stature in the fields of art and design—to discuss DeLorenzo’s career, the state of the design market today, and its future.

Like many dealers and collectors, DeLorenzo seemingly has what a psychologist might call an “acquisitive disorder”—a need to accrue more, even when you have a lot as it is. This December, in a three-part sale at Christie’s New York—highlighted by an evening sale on the 14th—DeLorenzo will sell more than 127 pieces from his personal collection and business inventory. (DeLorenzo explains that he is simply trying to downsize; Brant joshes that Tony is always saying that …) Lots range from Eileen Gray’s “Sirène” chair of 1912, made of lacquered wood with a velvet seat cushion (estimate: $2 million–$3 million), to a velour-upholstered Vladimir Kagan sofa, estimated to sell for $8,000 to $12,000. The auctions portend to be among the top events of the season.

PETER M. BRANT We have known each other for a long time. What were you doing before you got into the furniture business?

TONY DELORENZO I was in scrap metal, in the 1960s, in Brooklyn.

Tell me first how you got interested in furniture.

What happened was I bought a house on Long Island, while I was kind of making money in the scrap business. And the guy who owned the house said, “You want old fixtures?” I said, “I’ll take them, how much?” He said, “Thirty-five bucks, except for this one. It’s three thousand.” I said, “Three thousand?” He said, “Yeah, it’s Tiffany.” I said, “Tiffany, okay.” And it stuck in my mind.

So one day I went to [New York’s premier Louis Comfort Tiffany and Tiffany Studios dealer] Lillian Nassau’s—she was the queen—and I looked at a lamp that blew me away. I had three thousand in my pocket and Lillian said, “nine thousand five hundred, young man.” I said “ninety-five hundred?” and I left. But it was on my mind. Three months later it was still there. The price was now twelve thousand five. We talked again two months later and she offered it to for me fifteen thousand. I thought: “This is the business for me.”

I bought one of my first pieces of art deco furniture from her, and it was great. I bought it in 1969 or 1970. I remember it was thirty-five hundred, and that was like a fortune to me.

But, with your interest in the lamp, your first association with decorative arts was really in glass.

Yeah, I was a Tiffany lamp collector by 1977 or ‘78, and I had a little shop on Long Island. I didn’t have a bunch of money, but I was kind of collecting. All of a sudden I had two European dealers come to me, a French guy and a German guy. And I said, “Look I’m going to take you to my home, I’ve got some really great stuff at home.” I had, at that time, thirty-eight really prime Tiffany lamps and two pieces of [art deco master designer Émile-Jacques] Ruhlmann furniture that I had bought cheap. They didn’t pay attention to the lamps. “How much for the Ruhlmanns?” they asked. “How much for those?” I said, “wait a minute … I took you here for the lamps!” I started to think, “you know, this is not a universal market, Tiffany lamps. I’m not going to get caught when the music stops.” So I went into twentieth-century furniture.

When was the first time you went to Paris?

It was 1979. The Concorde was $2,900 round trip.

When you went to Paris, you first started to deal with…?

I dealt with the top dealers and I got fleeced. At that time I might have spent three hundred— five hundred—thousand, which was a lot of money for me at that time.

And when I came back I found out I had overpaid for everything. So then I hired a guy from Long Island to teach me how to buy. And that’s how I started.

Did you find that provenance was very clear?

No. It was all loose then, because it was all cheap. Don’t forget I’m buying 1950s pieces and art deco in ’79.

But your formula from the very beginning was always to buy the best.

Right.

To try to get the best things and be very patient. Wait for your price…

Wait for my price. I don’t mind overpaying, but I would prefer to overpay at auction. Because it’s a record. Gives you a little press…

What’s the most exciting thing you ever bought? Really made your heart tick?

Well, there are some friends of mine in Colorado that I built a collection for— Michael Chow— in 1988.

Part of his collection?

No, I bought it all. Everything: 93 pieces. It was a big, big deal—there was a New York Times article.

Yeah, you know it’s interesting, because I was just visiting Michael at his house in California. And of course he has a lot of Ruhlmann there. He’s basically filled his house with design. He’s an interesting guy. I like him very much. And he’s really a man of great taste.

He started out as a collector. He was a stamp collector, or something. We’re at one of the sales here in New York. We were really good friends and we were looking at this table and I said, “Hey Michael, what do you think of this?” And he said, “What do you want that piece of shit for?” And then he bought it. He said, “That’s your first lesson.” I said, “Okay. I’m a good learner.”

That’s a great story. Getting back to Lillian Nassau: she had a great Ruhlmann dining room set in her shop for years. Andy [Warhol] bought a lot of things from her. Did Andy ever buy from you?

Andy did not buy from me, but oddly enough I went to Chicago recently and his dining room table was there.

Really?

It made its way from the [Warhol estate auction at Sotheby’s in New York] in ’88 to France and then to Chicago. Nice table. I didn’t get it, though …

Ileana Sonnabend [the late Manhattan contemporary art dealer] put together a great art deco collection. A lot of Ruhlmann. I think Antonio [Homem, her adopted son] has most of it. He’s a nice guy. But she started buying in flea markets in the ‘60s.

I bought a couple of small things from her. She traded with me.

So really, in the ‘60s, art deco was just really kind of “throwaway,” you know—it was kind of like awkward furniture.

Don’t forget they were still working in that style in 1938, and so there it was thirty years later—“used furniture.” That was the time to buy.

Yeah. It generally takes, what, like twenty years for something to go out of favor? So now it’s back in fashion and it’s pretty rare to find great art deco.

The market’s been pretty well mined.

So tell me: you’ve always been able to go on to the next level. You went into art deco. You were one of the first to collect furniture from the 1950s. You also started early buying 1960s stuff by [American studio designer] Paul Evans and people like that. So what do you think will be the next period of collectable furniture? Meaning how far back—say the ‘70s, the ‘80s?

One big problem with ‘70s pieces is that a lot of designers never kept good records, so you don’t know what the heck they did. I like [studio designer] George Nakashima because his records are methodical. You can get a piece and [his daughter] Mira can tell you that it was carved in 1970 for so-and-so and sold for such-and-such. I kind of like that. Provenance is always there.

So what do you think of the idea today in modern furniture of making pieces in numbered editions?

That’s a whole different angle. I don’t know. I don’t understand it.

I think that it’s basically a different way of marketing designer furniture, so you can know specifically how many there are, instead of having no idea. It gives a design some cachet.

I don’t know. I think that these days maybe there’s a little more interest in being in the money business than being in the art and design business. If a designer has talent and his work is followed by a lot of collectors, then the edition will be twelve instead of one or two or three.

Who are your favorite ‘70 designers?

I like [French designer] Maria Pergay. I think probably a gal who will probably start to bring prices is [French designer] Claude de Muzac, which is a name a lot of people don’t know.

So where do you think the action is going to be in the future? The 1990s? Marc Newson?

I’m betting on the American market. I’m buying a lot of [American artist and designer] Albert Paley pieces and putting them away. It’s all hand-crafted, and he doesn’t do furniture any longer.

If you were giving advice to a young collector now—a person who’s twenty-five or thirty years old?

I would say buy Claude de Muzac. She’s good. The fashion designer, what’s his name, Marc Jacobs, is collecting de Muzac stuff a little bit. I would buy Albert Paley. I mean, you know if I’m buying Paley and not selling there’s got to be a reason: I think it’s too cheap.

And if you were advising an older, wealthier collector …?

The next move in the market is Ruhlmann. No question about it. This is my feeling.

Where do you find the biggest collectors of art deco right now?

Here.

Here in the U.S.? More so than in Paris, Greece, or the Middle East?

Absolutely.

Have you ever wanted to branch into art?

No, because every time I do I get burned. I don’t know it. So I may as well stick to furniture.

But you’re still — you still have the energy to go on.

I do, but things are getting a bit frazzled. I live in Florida. I have three houses and I have one apartment. What the hell do I need twelve bedrooms for?

I’ve known you for sure since 1980. And since I’ve known you, you’ve been complaining about the business. “It’s too much work. I don’t want do it. I’m going to Tahiti.” But you always show up and you’re always at the auctions and in the action.

But you know when I was young I was a gambler. This is just an extension of it except with this, you don’t bet on a horse or a lottery number. You bet on yourself.

But you love to do it.

I love to gamble.