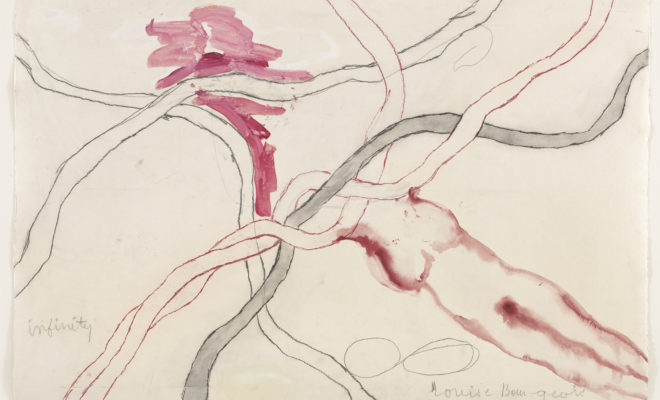

No. 5 of 14 from the installation set À l’Infini, 2008. All artwork by Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010). Soft ground etching, with selective wiping, watercolor, gouache, pencil, colored pencil, and watercolor wash additions. Sheet: 40 by 60 inches. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchased with funds provided by Agnes Gund, Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis, Marlene Hess and James D. Zirin, Maja Oeri and Hans Bodenmann, and Katherine Farley and Jerry Speyer, and Richard S. Zeisler Bequest (by exchange). © 2017 The Easton Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, NY.

No. 5 of 14 from the installation set À l’Infini, 2008. All artwork by Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010). Soft ground etching, with selective wiping, watercolor, gouache, pencil, colored pencil, and watercolor wash additions. Sheet: 40 by 60 inches. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchased with funds provided by Agnes Gund, Marie-Josée and Henry R. Kravis, Marlene Hess and James D. Zirin, Maja Oeri and Hans Bodenmann, and Katherine Farley and Jerry Speyer, and Richard S. Zeisler Bequest (by exchange). © 2017 The Easton Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, NY.

Exhibition

Louise Bourgeois in Print

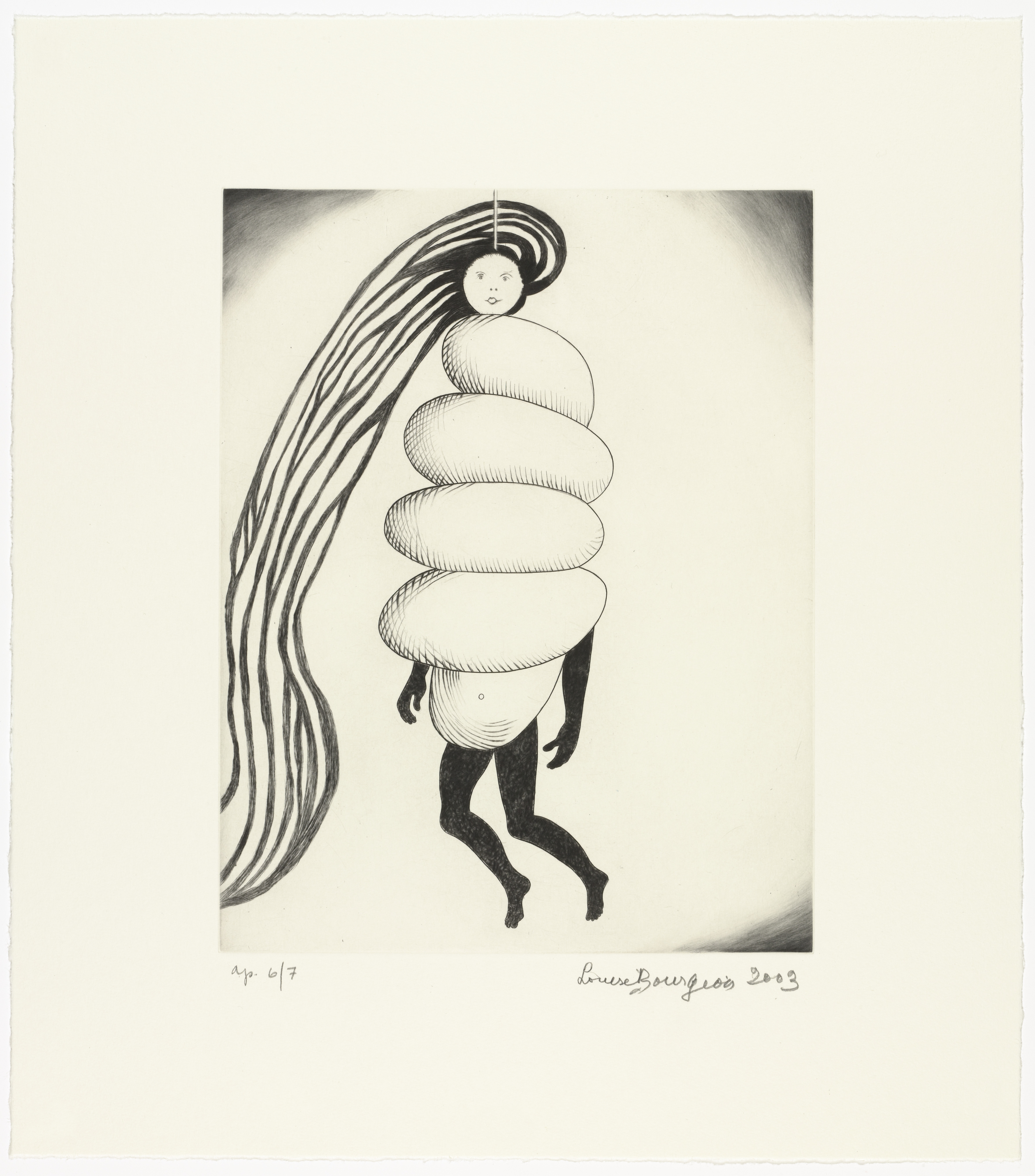

The artist Louise Bourgeois (1911–2010) had a tormented emotional life, but an unusually long and richly creative one that began and ended with vibrant and dynamic drawings and prints. Though she is best known as a sculptor, it was through draftsmanship that she first confronted the torrent of her feelings. Bourgeois developed a visual language and a repertoire of figures, like the spider who eventually became her signature Maman with wiry legs that can—through trick of the eye and trick of the hand—appear to be a woman with long hair. The Museum of Modern Art’s finely curated new exhibition, Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding Portrait, on view through January 28, 2018, includes some key sculptures and paintings, but focuses on 265 graphic works, demonstrating the assurance of her design as she unfolded artistically.

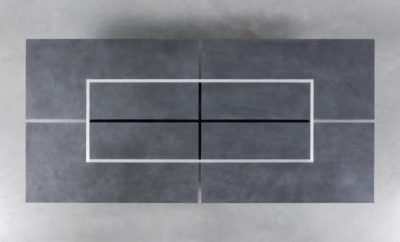

Installation view of Louise Bourgeois: An Unfolding Portrait. Museum of Modern Art, New York, September 24, 2017–January 28, 2018. Photo by Martin Seck for the Museum of Modern Art © 2017 The Easton Foundation/Licensed by VAGA, NY.

One of the standouts in the show is a book of engravings, He Disappeared into Complete Silence, dating from 1947, a testament to Bourgeois’s early intellectual versatility which extended from the visual arts to poetry. The book is comprised of nine enigmatic fables—narratives of love, disappointment, misunderstanding, and violence—each a few sentences long. She illustrates them with pillars, houses, ladders, stairs, and densely delineated skyscrapers—the architectural elements representing human figures. As in the work of Klee or Miro, the simple and almost childlike pictorial vocabulary allows complex emotions and memories to play out, while the fluency of moods and imagination translate into energetic compositional lines. When Bourgeois returned to printmaking in the late 1980s, she literally picked up where she left off, sometimes returning to work on the same plates or series of compositions. She brought new self-assurance to the old themes of isolation and self-reflection, and that artistic boldness distinguishes the later self-portraits, renderings of tall buildings, and memory landscapes, where the kinetic lines flow in waves over the printed paper.

Louise Bourgeois at the printing press in the lower level of her home/studio on 20th Street, New York, 1995. Photograph by and © Mathias Johansson.

Bourgeois’s extraordinary vitality and plasticity have been an inspiration to artists who have followed. The last graphic work, executed when she was in her late nineties, is both monumental and magisterial. By this time, it was common for the printers to work in her house as she sat in a wheelchair while assistants turned the plates around the table according to her instructions. The highlight of the exhibition, the installation, À l’Infini, is made of sets composed on two horizontal plates and printed on paper measuring forty by sixty inches long. Though you can detect floating bodies, amniotic sacs, pencil squiggles, and a birth cord twined like vine in the compositions, the prints are fluid and abstract, suggesting the indeterminacy Bourgeois was approaching, with a new poignancy.