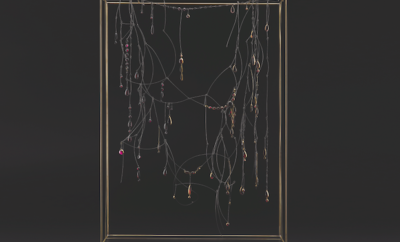

Evening belt by Elsa Schiaparelli, 1934. BROOKLYN MUSEUM COSTUME COLLECTION AT THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, GIFT OF THE BROOKLYN MUSEUM, GIFT OF ARTURO AND PAUL PERALTA-RAMOS.

Evening belt by Elsa Schiaparelli, 1934. BROOKLYN MUSEUM COSTUME COLLECTION AT THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, GIFT OF THE BROOKLYN MUSEUM, GIFT OF ARTURO AND PAUL PERALTA-RAMOS.

Exhibition

Jewelry gets its due as an art form

Jewelry is a challenging category in decorative arts. Though more than just ornament, it is often weighted down by religious and cultural associations, and treated as ethnological objects rather than art. But that is changing, as an important new exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York suggests. The Body Transformed, which opened on November 12 and remains on view through February 24, showcases some 230 objects drawn almost exclusively from the Met’s own vast collections, and involving all seventeen curatorial departments. The largest exhibition of its kind ever organized by the museum, it approaches jewelry as a universal art form; the opening label notes that it is also the oldest one, predating cave painting by thousands of years.

Gold Sandals and Toe Stalls by an unknown maker, Thebes, Egypt, c. 1479–1425 BC (New Kingdom, reign of Thutmose III). METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, FLETCHER FUND.

Focusing on the multiple meanings of jewelry and the ways in which it is used, the exhibition is not a glittery display of drop-dead pieces (although some are unquestionably that), but a serious and scholarly examination of the meaning of jewelry and its applications across times and cultures. It covers the history of jewelry from 2600 BCE to the present—the oldest pieces are from the ancient Royal Cemetery at Ur, and the newest are by Daniel Brush and Shaun Leane. Along the way, photographs and paintings illustrate the ways various societies have worn jewelry. Black backgrounds and dramatic lighting turn the galleries into a sequence of jewel boxes, in which the glass-encased, spotlit objects stand out like so many treasures.

Bone Cuff by Elsa Peretti, 1971–74. BROOKLYN MUSEUM COSTUME COLLECTION AT THE METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, GIFT OF THE BROOKLYN MUSEUM, GIFT OF MRS. STANLEY MORTIMER.

The opening gallery arranges objects in a series of glass-enclosed columns according to the part of the body they are intended to adorn—a dramatic display that pairs Egyptian sandals from the fifteenth century BC with an anklet from 19th-century Africa, and rhinestone-studded Saint Laurent earrings from the 1980s with a gold pair from 5th-century Korea, the latter looking even more wearable than the more recent ones. The groupings immediately illustrate the commonalities among objects that are centuries apart.

For the following galleries, instead of the usual chronological sequence, the curators chose a thematic plan, highlighting the different ways in which jewelry is perceived and how it is used to transform the body: to signal divinity, as a symbol of regality or power, to conjure ancestors or spirits, as adornments for allure, or simply for display. Objects from the ancient world are counterpointed with ones from Africa and Oceania, Central America, Europe, and (more recently) America. Modernists will find much to admire in contemporary works as well as in many that are centuries old, and the presentation encourages drawing connections between otherwise unrelated works: a body-hugging yashmak by Shaun Leane for Alexander McQueen that evokes a medieval suit of armor, or an elegant aluminum and diamond torque by Daniel Brush that is sibling to a gold Celtic one from the first century. Marquee-name designers like Rene Lalique (a fabulous enameled necklace from c. 1897), Alexander Calder (a 1940 curlicue brass necklace), Elsa Schiaparelli (a 1934 belt with crossed plastic hands in place of a buckle), and Paloma Picasso (a silver snake necklace and her famous bone cuff from the 1970s) vie for attention with the work of anonymous craftsmen. Throughout the exhibition, gold is the most-seen material, and the most arresting, even without the addition of jewels. To enjoy the unaffordable treasures, there’s a handsome catalogue to take back home.

Necklace of Lentoid Beads, String of Lentoid Beads, and Heart Scarab of Manuwai by an unknown maker, Thebes, Egypt, c. 1479–1425 BC (New Kingdom, reign of Thutmose III). METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, FLETCHER FUND.

Reinforcing the Met’s approach, jewelry as a decorative art is the concept behind L’École, School of Jewelry Arts, the Paris-based school sponsored by Van Cleef and Arpels that took up residence in an elegant East Side mansion from October 25 to November 9. An enthusiastic audience of collectors, jewelry wearers, and decorative arts aficionados signed up for a variety of classes in the history and traditions of jewelry and hands-on introductions to jewelry-making processes. L’École also presented three free public exhibitions: a private collection of gem-rich jewels; re-creations of twenty lost diamonds once owned by Louis XIV; and Daniel Brush: Cuffs and Necks, an extraordinary series of 117 chokers and 72 bangles of aluminum inset with tiny diamonds—as much artworks as they are ornaments.

Wrapping up the subject in a week-long series of exhibitions, studio visits, product introductions and special events, the first New York Jewelry Week, from November 12 to 18, reached out to a wider and less elitist market, reinforcing the idea that, with all its iterations and museum-worthiness, jewelry is an art form that anyone can afford.

Necklace (or belt) in the form of a snake by Elsa Peretti, 1973–74. METROPOLITAN MUSEUM OF ART, IRENE LEWISOHN BEQUEST.