For us, light is a material that we use to do sculpture,” says Hannes Koch, who, with Florian Ortkrass, co-directs Random International. “We’re really un-functional in our approach, other than a huge passion for design in what we do.” Indeed, the best-known work (so far) from Random International is a museum installation that focuses on water rather than light—Rain Room—which was donated to the Los Angeles County Museum by RH (Restoration Hardware) shortly after ending its long run there.

Random dates back to 2005. Koch and Ortkrass (a third partner, Stuart Wood, is now on his own) had just finished a mas- ter’s program at the Royal College of Art in London, where they launched their practice (the main studio is in London, though Koch is based in Berlin), and soon began to investigate the artistic potential of some fairly heady topics such as predictive analytics, artificial intelligence, and collective behavior, to wit: swarm theory. By 2008 they were working with Carpenters Workshop Gallery. Random is still represented by Carpenters in London, Paris, and New York, as well as by Pace Gallery in London, New York, and Shanghai.

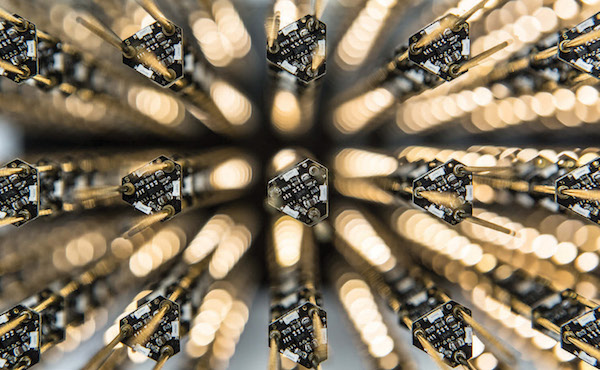

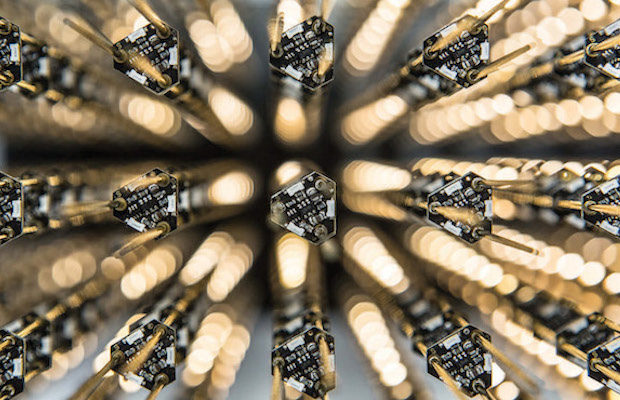

The first major project, Swarm, used sensor technology based on a behavioral algorithm to light up as viewers passed underneath and “swarm” (like locusts, or bees) in response to sound. It was shown by Carpenters Workshop at London’s Pavilion of Art and Design in 2009 and then in subsequent venues, including Design Miami’s, where both the installation and its young designers garnered enormous attention. The ideas that propelled Swarm remain a top preoccupation at Random, according to Koch. “At first we only scratched the surface,” he says. “We wanted to make something autonomous, highly efficient, and highly aesthetic— something beautiful and yet mysterious.”

COURTESY CARPENTERS WORKSHOP GALLERY

It is all a comment, an artistic response to human behavior but one couched in a technological framework that mimics nature. Koch points out that what he calls a “dark swarm,” as with locusts, can be a particularly disturbing event (the insects swarm to protect themselves from being cannibalized by each other), but at the same time “no matter how dumb the individual rules and behaviors are, the collective action produces something beautiful.”

Random continues to expand the research—as well as the design and artistry—behind Swarm and test it in new iterations with installations, including one (it is called Swarm XI) over the bar at the Park Hyatt New York. Yet the studio’s investigations into other areas (a number of them, including rain, do not involve light) continue on. A new series, entitled “Fifteen Points,” investigates the level of information needed for robotically engineered machines (in this case LEDs connected by rods to pulleys all custom-driven by motors that are directed by computer software) to recognize and imitate the human form. Another work, Cold Cathode Fluorescent Structure/II, uses lights to create abstract silhouettes of passersby.

Each project is subjected to what Koch terms “a ruthless internal process” in which the two principals must persuade the rest of the team (it numbers just shy of twenty people) of the clarity of their thinking and build the “narrative” of their work. On Random’s team is a dramaturge to make sure that the work truly tells its story, even if the ideas are often quite theoretical and abstract. “It’s important,“says Koch, “to stay really true to your vision.”

-Beth Dunlop

COURTESY CARPENTERS WORKSHOP GALLERY

COURTESY CARPENTERS WORKSHOP GALLERY