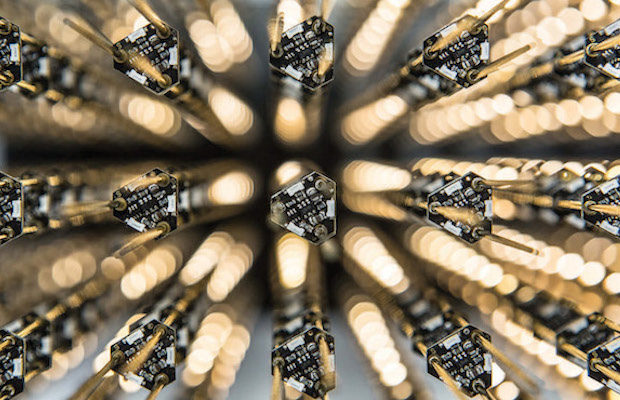

It is no exaggeration to say that no one who’s seen Studio Drift’s first full-edged lighting project—it’s called Fragile Future—can forget it. Fragile Future began, fairly simply, as Lonneke Gordijn’s final student project at the Design Academy Eindhoven. Long fascinated by dandelions (“It was the first plant I knew by name,” she’s said), she went out into the fields and picked their pods, took them apart, and then reassembled them, attaching each of the feathery “parachute” seeds to a tiny LED.

Quickly the project evolved, in conjunction with fellow Eindhoven graduate Ralph Nauta, into Studio Drift and the spellbinding Fragile Future—hundreds of dandelion seed heads suspended in a brass cage that is actually constructed from electrical circuits. “It worked out perfectly and the hard light was spread so organically and softly,” Gordijn says. “This was the first time that I realized that nature and technology did not have to be enemies, but could also be connected with each other and even share a similar size and aesthetic.”

From its debut in an early iteration at Design Miami Basel in 2009 and subsequent showing at the Pavilion of Art and Design in Paris (where the edition sold out), Fragile Future morphed and grew and remains a showstopper—most recently at FOG Design+Art in San Francisco—still fresh and full of hope, even if it also poses its own set of philosophical (and cautionary) questions about man and nature. Gordijn calls it “a symbol for the circle of life.”

“A lot of art comes from a dark place,” says Nauta. Together, he and Gordijn have veered away from those darker places to create work that uses cutting-edge technology to celebrate nature. The work indeed moves away from cynicism into a far more hopeful place. “It’s difficult,” Nauta admits, “because when you set out to create beauty, it can come very close to kitsch.”

COURTESY STUDIO DRIFT

Nauta and Gordijn continue to pursue the beautiful as well as the ephemeral. Today their work is represented by both Carpenters Workshop (which has galleries in Paris, London, and New York) and Pace Gallery (London, New York, and Hong Kong) and resides in the permanent collections of the Victoria and Albert Museum, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, both the Rijksmuseum and the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam, and the Museum Voorlinden in Wassenaar, Netherlands.

With Shylight, which is in the permanent collection of the renovated Rijksmuseum, and has been shown at both the Israel Museum in Jerusalem and the Museum of Arts and Design in New York, they have created an installation based on the circadian movements of certain owers, which is called nyctinasty; the large silk flowers open and close slowly, sometimes seeming to dance (waltz, really), though without music. “You have a certain movement, but then you slow it down,” Nauta says. “Then, when you walk away, it feels like you’ve discovered a new life form, and you have new hope, showing you a new direction.”

Flylight, which springs from a similar curiosity but examines a different natural phenomenon—migrating flocks—explores the way a flock of birds moves. Programmed with specially developed software, Flylight involves glass tubes suspended as if they were wings lit up in a way that is both predictable and unpredictable. “We work with light in a non-functional way to translate energy and to tell a story.”

Always, there is nature. “This is the only place where you find constant changing self-organizing mechanisms that always seem to be adaptive to situations and make it work,” Gordijn says. Studio Drift represents nature in ways that are both artistic and highly technological—and intended to get to its essence—in work that is propelled by, as Gordijn says, “observation, disbelief, curiosity, the ‘What if?’ question, and mainly visions of dreams, of what could be.”

-Beth Dunlop

COURTESY CARPENTERS WORKSHOP GALLERY

COURTESY CARPENTERS WORKSHOP GALLERY