John Sebastian performing at Woodstock, 1969. © Henry Diltz / Corbis

John Sebastian performing at Woodstock, 1969. © Henry Diltz / Corbis

Exhibition

If You Remember, or In Case You Don’t: You Say You Want a Revolution at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London

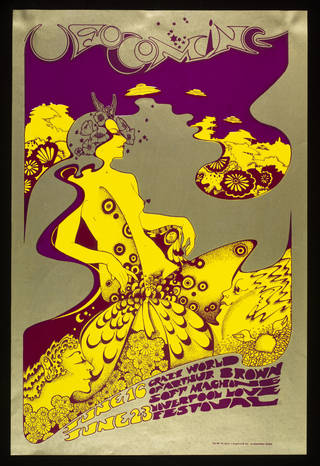

Poster for The Crazy World of Arthur Brown at UFO, 16 and 23 June, by Hapshash and the Coloured Coat, 1967, London (Michael English & Nigel Waymouth). Photograph © Victoria and Albert Museum, London

A mélange of rock music and corresponding album covers designed with bold hand-lettering or bursts of psychedelic swirls in clashing colors welcomes you into the Victoria & Albert Museum’s blockbuster multimedia show, You Say You Want a Revolution, Records and Rebels, 1966-1970. If you’re wearing a headset, Bob Dylan’s “The Times they are A-Changin” comes on and fades out then moves on to Buffalo Springfield and Otis Redding.

The exhibition, which closes February 26, marks fifty years since the Beatles made the decision to work full time on recordings rather than live performance, and the golden age of the LP was born. The music of the 60s coincided with creative fervor as well as a set of revolutionary ideas. As curator Geoffrey Marsh points out, it was a youth revolution “about young people with a desire to live differently and think differently from their parents’ generation… and to look differently.” But its roots were in the Cold War and the civil rights movement and John Kennedy’s words “Ich bin ein Berliner” are embedded at the beginning of the soundtrack since the revolution, above all, was about breaking barriers.

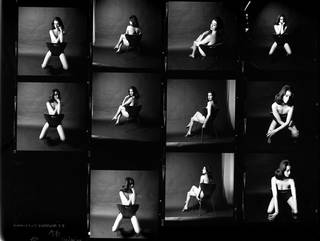

The show is filled with historical artifacts: a mod Twiggy mini dress and accompanying Twiggy London Girl hanger stamped with the image of her pretty pouting face, an Arne Jacobson stacking chair like the one Christine Keeler straddled while naked (fatally damaging Harold Macmillan’s conservative government), John Lennon’s wire framed glasses with round ‘granny’ lenses similar to the ones worn by the Bolsheviks, and an A-line paper Souper Dress that originally could be purchased from the Campbell Company by mailing in labels from their vegetable soup cans. San Francisco Mime Troupe is represented by a set of papier maché puppets one with with President Lyndon Johnson’s long, craggy face and another the sad countenance of a Vietnamese Mother that take you back to the raucous creative magic of free street theater.

The revolution advocated in the White Album and Hey Jude challenged conventional thinking that separated taste and tastelessness, old-fashioned and new, permanence and impermanence, high art and low, as well as male and female, black and white, east and west, the mind’s eye and the far-out “sky with diamonds” — but sometimes it also confronted cruel reality.

ARLINGTON, VA – OCTOBER 26 1967: Antiwar demonstrators tried flower power on MPs blocking the Pentagon Building in Arlington, VA on October 26, 1967. (Photo by Bernie Boston/The Washington Post via Getty Images)

One of the more extraordinary objects on view is a bronze replica, now owned by the Oakland Museum of California, of the wicker peacock chair Huey P. Newton posed on while holding the nose of a shotgun in his right hand and a spear in his left. The peacock chair, originating either in Manila or the Philippines, was prized by Victorians who found good use for it on shaded verandas. It returned to popularity in the sixties. With the fanning-out, throne shape, the chair was a perfect prop for a Black Power poster in which the intricate mandala surrounded Newton like an aureole and turned assumptions about privilege upside-down.

Christine Keeler, photographs by Lewis Morley, 1963. © Lewis Morley/National Media Museum/Science & Society Picture Library

Just as rock music was increasingly crackling with overridden amplifiers and new sound technologies, Expo 67 opened with Buckminster Fuller’s geodesic dome and Stanley Kubrick released 2001: A Space Odyssey, choosing to use Djinn chairs on his futuristic sets. Low to the ground and armless, the magenta-red chair on view looks like a little robot or analog human being who might come along on a magical mystery tour.

The highlight of the show is the gallery where the film Woodstock is shown on large screens suspended above a display of costumes from the festival like Mama Cass’s red velvet caftan. Viewers sit on lie down on the museum’s synthetic grass, many of them lip syncing along. A young Joan Baez with a pixie cut sings the ballad of Joe Hill and Jimi Hendrix performs the “Star Spangled Banner” which lasts three minutes and forty-six seconds. Everyone holds their breath as if they were there back in those changing times.