Exhibition

HIPPIE MODERNISM AT THE WALKER

Ode to an Earlier Era, Though Not a Simpler One

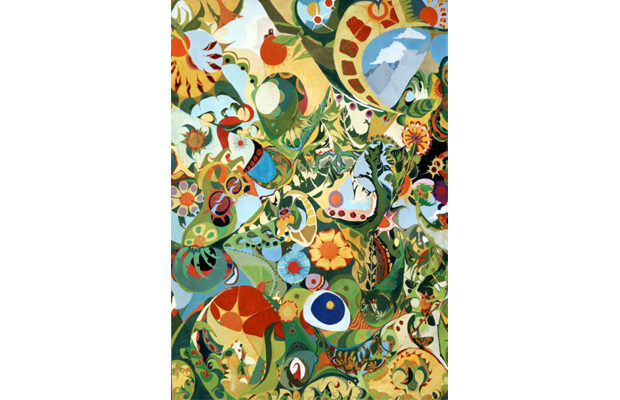

ISAAC ABRAMS, HELLO DALI, 1965

A new show at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis presents works from the counterculture of the 1960s and ’70s. The exhibition, Hippie Modernism: The Struggle for Utopia (September 10–December 31, 2016), seeks to reexamine the often marginalized and overlooked contributions of artists, designers, architects, and other experimentalists of the era. Working in conjunction with the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archive, Walker curator Andrew Blauvelt has assembled pieces and artifacts that range from psychedelic paintings and multi-media room installations to techno-utopian design modules and early computer art. The exhibition highlights the variety of artistic disciplines and socio-political attitudes of the period, which extend far beyond the traditional stereotype of the “hippie” in popular culture. As suggested by the exhibition’s title, the inclusion of works such as the Haus-Rucker Company’s Flyhead helmet, which augments the wearer’s visual and audio perception, and John Whitney’s motion graphics videos emphasize the role of technological and media innovation towards the promise of revolutionary utopia that shaped the hippie ideal. “The goal was to liberate technology from the corporate and military users… it’s no accident that the philosophy of personal computing and figures like Steve Jobs eventually emerge from this era,” Blauvelt notes.

Although the show does rework many preconceived notions of the hippie artistic movement, it does not gloss over the importance status of sex, drugs, and rock music in presenting a holistic vision of the times. The installation CC5 Hendrixwar/ Cosmococoa Programa-in-Progress by the Brazilian artists Hélio Oiticica and Neville D’Almeida features cocaine powder drawings of Jimi Hendrix projected on the walls of a room filled with hammocks to be “occupied” in a further allusion to the protest tactics of the time. Psychedelic paintings by Isaac Abrams and the Vancouver-based Judy Williams—the latter of whom actually painted while in an altered state—pay tribute to Timothy Leary’s “turn on, tune in, drop out” mantra. On the other hand, the mylar chamber photographs of Ira Cohen, which include another portrait of Hendrix, demonstrate how these aspects of hippie culture coincide with the application of technology in art, as Cohen augmented his studio to create a psychedelic effect.

For Blauvelt, the artistic movements of the radical ’60s and ’70s have always intrigued him as a designer and curator. The prints of Sister Corita Kent and Sheila Levrant de Bretteville, and even the iconic rock show flyers all laid the groundwork for contemporary graphic design; Blauvelt also cites such architects as Rem Koolhaas as drawing inspiration from this era. Yet within the art world, the hippie artists have been relegated to the status of side notes, with techniques like psychedelic painting omitted in revisions of art history texts that once included them. Blauvelt attributes this partly to the fact that other movements such as minimalism, conceptualism, and pop art take precedence over the often ephemeral, performance-based art associated with Haight-Ashbury through troupes like the activist Diggers and the gender-bending Cockettes. However, while much of the social history focuses on the failure of hippies and revolutionaries within this time period, the lasting outsider status of these artists might actually point to a kind of success. In keeping with the spirit of liberation and democratization, artists turned their focus away from material object art into cross-disciplinary and collaborative efforts such as the Company of Us (USCO), whose early experiments with lighting installation art are featured in the show. “Collectives like USCO inverted the idea of the artist as owner and sole creator,” says Blauvelt, a marked contrast from an artist such as Andy Warhol, who received almost all the credit for his Factory’s output. “For the hippies, art was a part of everyday life.”