Pulegoso Vase by Napoleone Martinuzzi, ca. 1930, Italy. Image courtesy of Wright.

Pulegoso Vase by Napoleone Martinuzzi, ca. 1930, Italy. Image courtesy of Wright.

Uncategorized

Handle with Care #5

Launched by our sister publication The Magazine ANTIQUES, Handle with Care offers monthly insights into the fields of ceramics and glass, both contemporary and historical. We’re now happy to begin sharing Sarah Archer’s reports with readers of MODERN. This is the fifth installment of the column; links to earlier editions can be found below.

We’ve retained some of that December joie de vivre in the form of modern holiday celebrations. We overindulge a bit, reflect on the year, think of where we could have done better, and promise to straighten up and fly right come January, after one last cookie or sip of eggnog. Fortunately, January comes but once a year. And appropriately for the season, there is an entire exhibition of objects inspired by one (or more) of the seven deadly sins in “The Virtue in Vice,” on view through March 25, 2018 at the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum in New York. The inspired selections of objects in this show suggest the Seven Deadly Sins: pride, greed, lust, envy, gluttony, wrath and sloth. A “Roomba” vacuum cleaner from 2005 presumably represents laziness; an 1875 silk-lined traveling dressing table set suggests vanity; and a luxurious gilded porcelain cooler from the 1790s must point to intemperance.

There are terrific recent works on view as well, like ceramist Matt Nolen’s “Credit Card Reliquary Vase” from 1991—a kind of funerary urn for late capitalism, perhaps—meticulously decorated with the well-known emblems of MasterCard and Diners Club International, set inside roundels where you might expect to see a low relief portrait in profile.

“Credit Card Reliquary Vase and Lid” by Matt Nolen, porcelain, 1991. Museum purchase from Decorative Arts Association Acquisition Fund. Image courtesy of the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum.

Some works perfectly exemplify the conceit of the exhibition’s title: though they may be associated with indulgence, we should revel in their material magnificence without guilt. One such object is an incredibly delicate favrile wine glass by the Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company in 1900 under the direction of Louis Comfort Tiffany, who introduced the term “favrile” to the world of glass. Tiffany patented the a translucent type of glass in 1894, and based his new word for it on the Old English “fabrile,” related to our word “fabricate,” meaning “handmade.” He used metallic salts to give favrile glass its trademark iridescence, and found plenty of virtue in the fact that each piece was unique and apt to have idiosyncrasies.

Wine Glass, mouth-blown favrile glass, ca. 1900, Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company. Bequest of Joseph L. Morris. Image courtesy of the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum.

Speaking of virtuous idiosyncrasies in silica, a constellation of jaw-dropping Italian vessels shone brightly in the Wright auction house’s November 21st Masterworks sale of Important Italian Glass. Most of the glass dated from the 1920’s and ‘30’s, which wouldn’t necessarily be obvious to the casual observer. Unlike much iconic Art Deco glass from the studios of Daum Frères or Sabino, with their trademark geometric surface designs and machine age silhouettes, the Venetian glass in Wright’s sale seems almost timeless. “The 1920s and 30s were a very important period for Italian Glass, the main reason being that this was the era in which Modernism was introduced to the field,” says Richard Wright. “It is true that in the Twenties and Thirties that many of the forms were derived from shapes in classical antiquity, but we also see the influence of modernism.”

Mosaico Tessuto Vase by Paolo Venini, Italy, 1954. Image courtesy of Wright.

Each vessel offers a particular thrill. A soffiato vase made at the Vetreria Artistica Barovier around 1930 is practically postmodern: its clear glass body is bedecked with brilliant red pasta di vetro handles stretched to extreme angles, and a touch of shimmery silver leaf overall. It sold for $32,500. Paolo Venini’s mosaico tessuto vase (“mosaic of fabric”), which is a bit later, from 1954, is like a translucent textile shot through with vivid colors. Venini drew inspiration for this technique from fabric designs, arranging glass tesserae in alternating patterns to make the glass appear as though it had been woven like a lattice. Venini’s vase sold for $117,500.

Soffiato Vase by Vetreria Artistica Barovier, Italy, ca. 1930. Image courtesy of Wright.

And though it seems almost impossible to choose one stand-out from this group, Richard Wright identifies Napoleone Martinuzzi’s ten-handled pulegoso vase ca. 1928 as the most unusual and striking work in this sale. This is partly because of its rarity: the luminous green vessel is one of only five of its type known in the world. Its materiality is important, too: “Pulegoso glass was Martinuzzi’s invention, which he based on an earlier type of glass he discovered in the Museum of Glass on Murano. His choice to use it for large sculptural vases was a revolutionary moment in the history of Murano glass. He brought the use of opaque glass to Murano and since Martinuzzi was a sculptor, this sculptural plasticity was new.” The outrageous handles, perched one on top of the other, hint at the playfulness and wit of Surrealism and Dadaism, offering the main clue that the piece isn’t entirely inspired by ancient forms. First exhibited at the Venice Biennale of 1928, the vase wowed critics even then, and its dazzle factor remains intact. This piece blew past its presale estimate of $100,000–150,000 to bring $269,000.

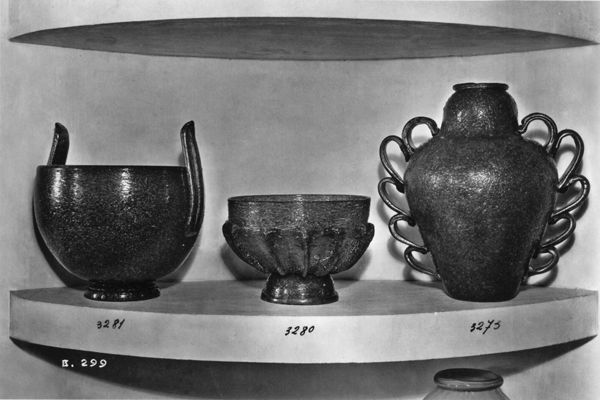

Works in Pulegoso glass exhibited at the IV Triennale di Monza, 1930. Image courtesy of Wright.

Amphorae have been more or less taken out of service in the practical sense, but a major recent archaeological find in Georgia reminds us that our knowledge of ancient winemaking practices would be scant without them. Earlier this month, the New York Times reported the results of a new study in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences announcing that shards of neolithic ceramic vessels unearthed in at the the Gadachrili Gora site, about 30 miles south of Tbilisi, bear traces of tartaric, malic, succinic and citric acids.

The excavations at the Gadachrili Gora site in Georgia. Photograph by Stephen Batiuk.

Though it likely won’t ring any bells for the typical wine connoisseur, this particular combination of acids occurs only in grape wine. This discovery moves the estimated date of the earliest instance of winemaking from grapes back to around 6,000 BC, according to Dr. Patrick McGovern, a molecular archaeologist from the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. It also suggests that in addition to having mastered pottery early on, Georgia may be the first place where grapes were successfully cultivated.

A Neolithic jar found at the site of Khramis-Didi-Gora in Georgia, on display at the Georgian National Museum. Photograph by Mindia Jalabadze/Georgian National Museum.

Today, the Eurasian grape—native to the Caucasus—is used to make nearly every wine on earth. Wine chemist Andrew Waterhouse of the University of California, Davis notes that even earlier attempts at fermenting grapes may have involved animal hides, but as these prehistoric “barrels” were made from organic material and have long since decayed, pottery is the best source for dating the earliest attempts at viniculture. Raise a glass this holiday season, and don’t forget to offer a toast to the humble neolithic shard.

The base of a Neolithic jar recovered from a Neolithic site in Georgia. Photograph by Judyta Olszewski.

To read the first four installments of Handle with Care, visit The Magazine ANTIQUES’ website.