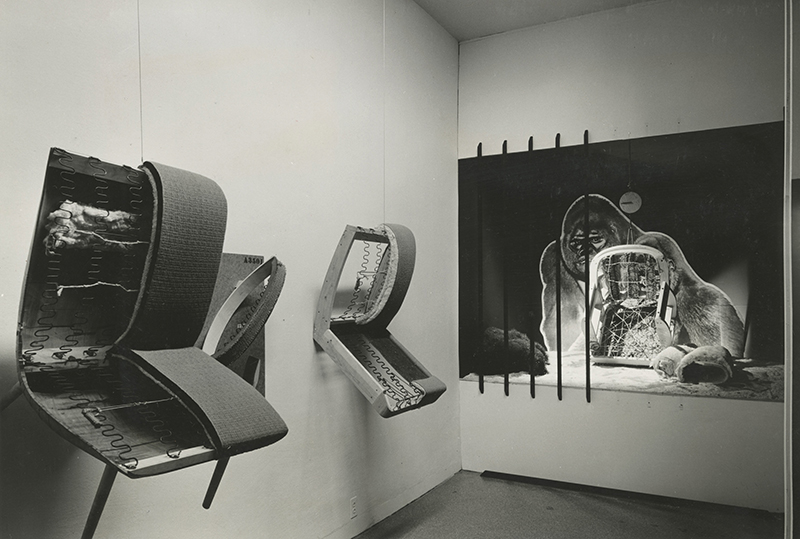

An installation view of The Value of Good Design at the Museum of Modern Art, up until June 15, 2019.

An installation view of The Value of Good Design at the Museum of Modern Art, up until June 15, 2019.

Exhibition

Good Times

WITHIN A FEW YEARS OF ITS FOUNDING, the Museum of Modern Art in New York began to promote the notion of “good design” through exhibitions of innovative furniture and accessories and product design competitions. How did MoMA define good design? Curator and architect Eliot Noyes could at least demonstrate what it wasn’t. Visitors to the museum’s Organic Design in Home Furnishings show of 1941 were met by a display case containing a traditional upholstered armchair, dismantled to reveal its thick padding, springs, and heavy wooden frame. Bars at the front of the display suggested the chair was being kept in a zoo cage, and a photo of an enormous gorilla served as a backdrop. Wall text described the chair taxonomically:

Cathedra gargantua, genus americanus. Weight when fully matured, 60 pounds. Habitat, the American Home. Devours little children, pencils, small change, fountain pens, bracelets, clips, earrings, scissors, hairpins, and other small flora and fauna of the domestic jungle. Is far from extinct.

Installation view by photographer Samuel Gottscho of the Organic Design in Home Furnishings exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art, 1941. PHOTOGRAPHIC ARCHIVE, EXHIBITION ALBUMS; © 2019 THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART.

That amusing moment is recalled by an image of the 1941 display in a current exhibition at MoMA entitled The Value of Good Design, which re-examines the museum’s program of advocacy for modern design in the mid-twentieth century and the principles that informed it. What constituted good design for MoMA was perhaps most succinctly yet comprehensively expressed in 1948 by curator Edgar Kaufmann Jr. “Good design in any period is simply,” he said, “a thorough merging of form and function, and an awareness of human values expressed in relation to industrial production for a democratic society.” That is, beyond utility, beauty, and commercial viability, a well-designed object had a sociopolitical dimension—good design was good for the nation.

Spacelander bicycle by Benjamin Bowden, 1946. GIFT OF THE GEORGE R. KRAVIS II COLLECTION.

MoMA’s earliest design exhibitions essentially presented gift ideas. To win converts to the new modern style, from 1938 to ’48 the museum hosted holiday shows with the term “Useful Objects” in the title. The first—Useful Household Objects Under $5.00—showcased items such as cookware, venetian blinds, a dishrack, and an orange juicer, and traveled to seven other venues nationwide. The next year the price point had risen (to $10) and so had aesthetic standards: Russel Wright’s American Modern tableware was on view as well as his carved hazel wood Oceana serving trays, alongside wooden wares by James Prestini and glass from Blenko and Orrefors. For 1947’s edition, the bar was set at $100 and the list of design luminaries with creations on display included everyone from Alvar Aalto to Eva Zeisel— with Charles and Ray Eames, Josef Hoffmann, Raymond Loewy, Gertrud and Otto Natzler, Marguerite Wildenhain, and many others in between. Earl S. Tupper, inventor of Tupperware, was represented, too.

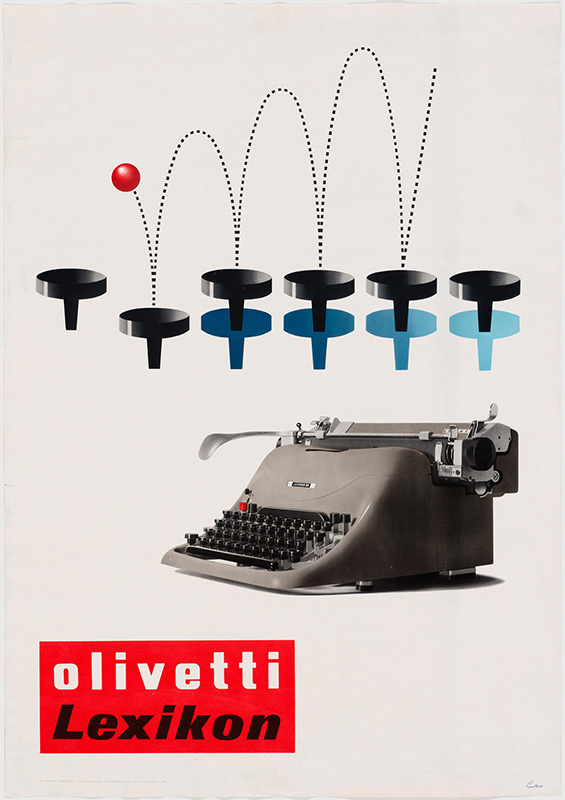

Olivetti Lexikon advertisement by Giovanni Pintori, 1954. GIFT OF THE DESIGNER.

MoMA design competitions, begun in 1940, provided a direct stimulus for modern design innovation. Winning projects would be exhibited at MoMA, and top prizes included a contract with a manufacturer and a distribution arrangement with department stores. Charles Eames and Eero Saarinen swept the awards for seating in the inaugural contest with a series of chairs made of molded plywood. They were displayed at the Organic Design exhibition in 1941. Following the war, and in response to the housing shortage that ensued in America and abroad, in 1947 the museum announced an international competition for low-cost furniture design. The prize-winning submissions were unveiled in 1950. Donald Knorr shared first prize in seating for his chair with a conical plastic seat that the judges described as “light, flexible, and elegant.” Honorees included designers from as far afield as Switzerland and Finland, Mexico and Japan. Many felt the contest helped spark their careers, and heartened national modern design industries. Even the heralded Danish designer Hans Wegner said that when the competition was announced: “We felt as if a window had been opened and we were given a chance to show what we could do.”

500f city car, designed by Dante Giacosa in 1957, this example manufactured in 1968. GIFT OF FIAT CHRYSLER AUTOMOBILES HERITAGE.

Billed as expanded versions of its annual holiday show, MoMA’s Good Design exhibitions of 1950 to 1955 were, for some, an uncomfortably commercial curatorial exercise as collaborations between MoMA and the Merchandise Mart in Chicago, where the exhibitions debuted before moving to New York. A fifteen-cent brochure was available at the museum with information on which stores sold items in the shows. MoMA also offered a “Good Design Kit” to US retailers that included sample store layouts, advertising, and logo labels to affix to designs that had been displayed in the exhibitions. Kaufmann, the program’s director, argued that the museum had “the responsibility of guiding the consumer toward those qualities which make an object beloved for generations.”

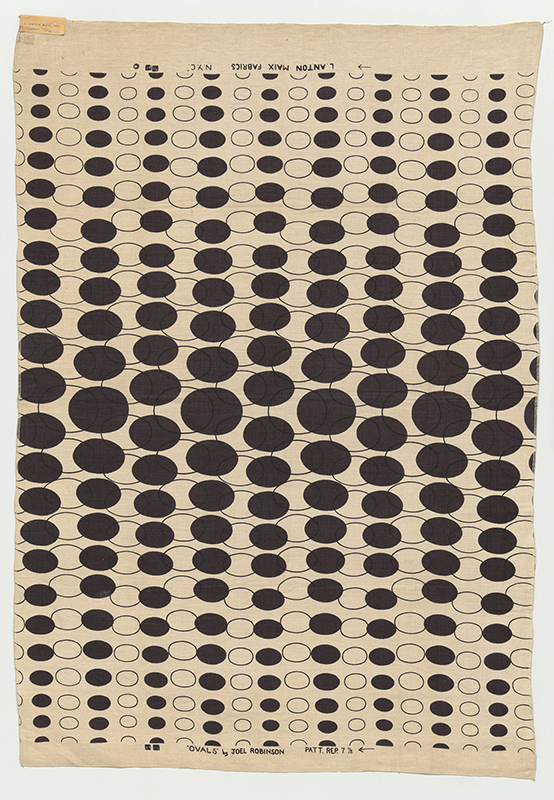

Ovals textile by Joel Robinson, c. 1951–1955. COMMITTEE ON ARCHITECTURE AND DESIGN FUNDS.

The curatorial guidance that informed MoMA’s Good Design exhibitions would also be put to more explicit propaganda purposes on a broader stage. Shows of modern design objects chosen by the museum’s curators, sponsored by the US State Department, were mounted during the Cold War years in places like Helsinki, Stuttgart, and New Delhi—palpable demonstrations of the superiority of the forward-thinking, prosperous American system.

Television model TX8-301 by Sony Corporation, 1959. GIFT OF JO CAROLE AND RONALD S. LAUDER.

But even with the ulterior motives behind them, the Good Design exhibitions brought into the public eye scores upon scores of wonderful, novel designs. Some on view in the current show at MoMA come under the visitor’s gaze like welcome old friends—such as Saarinen’s Womb chair, Greta von Nessen’s Anywhere lamp, a Lina Bo Bardi Poltrona Bowl chair, Sori Yanagi’s Butterfly stools, and the Eameses’ La Chaise (which appeared in the 1950 low-cost furniture exhibition as an aesthetic bijou, too costly to mass produce, and did not actually come to market until 1990). And there are surprises here, too, like the Ovals screen-printed linen fabric by Joel Robinson, the first black designer to have his work included in a Good Design show, found in the archives during research for the current presentation; or Charlotte Perriand’s Low chair, designed in 1940 and made entirely of light, strong, cheap, and fast-growing bamboo—an example of sustainable design sixty years avant la lettre.

Prototype for chaise longue (La Chaise) by Charles and Ray Eames, 1948. GIFT OF THE DESIGNERS.

Juliet Kinchin, curator of MoMA’s architecture and design department, and curatorial assistant Andrew Gardner have put together a marvelous survey of the museum’s mid-century modern design program. They may beg the question of MoMA’s international influence in that era by including works—a Fiat 500 auto, for example—with no direct connection to the museum’s design exhibitions, many of them from countries where modernist notions were developed long before they reached America. But that is a relatively minor quibble.

Anywhere lamp by Greta von Nessen, 1951. ARCHITECTURE & DESIGN PURCHASE FUND.

What perhaps makes The Value of Good Design most affecting is viewing the show in the context of today’s design world. In a time of growing income inequality, more and more people need well-made, useful, and affordable things. Yet many respected designers seem to be spending their talents either to produce pieces that demand to be viewed as art, or are made with such extravagant techniques and rich materials that only billionaires can afford them. Given that, it is almost poignant to be in the company of objects conceived and created by those who truly believed that good design was meant for everyone.