Feature

[From the archives] A house in Havana: A moment captured

As the opportunities to visit Cuba mount, MODERN returned to its archives to explore the island’s architectural treasures in this this story by Hermes Mallea from the Summer 2012 issue.

The glass wall of the stairwell providesa sense of merging inside and outside at the Pérez Farfante house in Havana.

The Pérez Farfante house speaks volumes about the sophisticated lifestyle in Havana on the eve of the 1959 Revolution, when the Cuban city was known as the Paris of the Americas in no small measure because of the excellence of its architecture. In the century between 1860 and 1960 Havana followed world architecture trends step-by-step to produce a prodigious body of beautiful residential buildings, including any number of unknown modernist gems, among them this house built for two sisters in the city’s Nuevo Vedado neighborhood. Such houses represent the culmination of the Cuban quest not just to emulate European and American architectural styles but to create highly original interpretations of mid-century modernism that would express Cuba’s national identity.

A marble-top table and Scandinavian armchair anchor an intimate sitting space in the second floor living room. On the table are 1950s ceramics by Cuban artist Amelia Peláez.

Sixty years after its construction, the house remains a clear articulation of the personal style of the sisters who commissioned it— Olga and Isabel Pérez Farfante—members of Havana’s mid-century intelligentsia, a golden generation for whom building a contemporary house was an expression of progressive values. The daughters of a small-town grocer and his schoolteacher wife who emphasized the importance of education on their children, both sisters balanced academic careers with family lives at a time when doing so was unusual for a woman— Olga as a dentist and teacher, Isabel as a Havana University biology professor who had graduated summa cum laude from Harvard. They chose a site with dramatic views in Nuevo Vedado just as the neighborhood was being developed—joining other young professionals building houses that reflect- ed a mid-1950s climate of optimism fueled by America’s postwar prosperity that had reached Havana’s upper and middle classes. Although the house is unmistakably modern—and the exterior appearance is marred today by a chain-link fence at the street level—the front has the elegance of a classical temple. Columns support the roof, and at the roofline a projecting thin concrete slab protects the house from sun and rain. Asymmetries of massing, windows, and corner treatments dispel the idea that its design is traditional, however. Concrete floor slabs are expressed as continuous horizontal planes on the facades. The walls are infilled from slab to slab with concrete block, glass, or wood louvers, allowing the function of an interior space to be read on the exterior. The rear facade, too, reflects the interior, including strip windows at the bathrooms, and perforations in the block wall to ventilate the service areas.

The wooden louvers can be adjusted to maximize the breezes and views of the landscape.

Architect Frank Martinez designed the house to address the traditional Cuban concept of extended family living, creating a duplex where two households had complete privacy under the same roof, yet could live communally when desired. In it he aimed for an international modernism with a Cuban flavor, recognizing the value of time-tested elements like adjustable wood louvers and the spatial ambiguity of outdoor spaces that function as living rooms and open-air galleries that are more than circulation spaces. The house is raised on slim concrete columns (or pilotis) above an open ground floor with space for cars, service areas, the entry stair, and a shaded seating area. Breezes circulating the air through this level help cool the living spaces above.

As in traditional Havana houses, balconies connect the residents to the life of the street. The louver walls can be slid away to incorporate this outdoor space into the core of the house.

The house reveals itself as one moves around and through it, but nothing prepares the visitor for the dramatic views that are framed by the architecture, the focal points that keep the eye moving inside, or the sense of delight when a wall slides away to turn an interior space into an open air one. Public rooms and bedrooms are placed at opposite ends of the structure, separated by a vertical recess containing what family members have called their “pre-living rooms,” which form the core of the house. Sliding open the louvered doors to the front balcony doubles the width of this core. When the corresponding louvers on the rear elevation are then slid open the core seems to dematerialize altogether, as the whole center of the house opens to views of the Havana woods and the ocean beyond.

The tubular steel and wood staircase, continually changing in the light, is visible from the front door of each apartment. Set toward the center of the rear facade, the stair acts as a vertical accent rising in its glass box. Thanks to the dramatic site and the light-weight design of the stairs, the user has a sense of drifting high above the landscape.

A 1950s still life by Cuban painter Angel Acosta Leon hangs against the stained-wood paneling on one wall of the second floor living room.

In a nod to the modern American lifestyle that Cubans were always emulating, the kitchen connects directly to the public areas. But middle-class Cubans of the 1950s had cooks and housekeepers long after the same income group in the United States had given up their servants, and the kitchen forms part of a clever series of service spaces, including laundry and maid’s bath, that are provided with their own set of spiral stairs, allowing servants to move around the house with-out going through the family rooms.

The stained wood paneling of the living rooms (shown is the third floor) flows into the dining room, where one section cleverly drops down to form a bar and a pass-through into the kitchen. The barstools are original—Cuban-made interpretations of mid- century designs.

Construction materials used on the exterior were carried indoors: the weathered concrete-block walls that meet the white concrete floor slabs, the glass and wood louvers, the concrete columns that rise three stories. This continuity of materials blurs the distinction between interior and exterior—an achievement of the best of Havana’s mid-century modernist houses.

The sisters furnished the house with advice from the architect, and remarkably much remains—Scandinavian classics by Hans Wegner and Knoll’s iconic Harry Bertoia chair as well as Cuban-made pieces that perfectly complement the 1950s architecture. The sisters also shared a love of contemporary Cuban painting, and works by Victor Manuel, Mirta Serra, and Hipólito Hidalgo de Caviedes are likewise still found throughout the house.

At the entry to the second floor apartment are a pair of Hans Wegner Sawbuck armchairs and a Scandinavian table and dining chairs.

Along with other “Tropical Modernist” houses in Havana, the Pérez Farfante house reflects a climate of architectural experimentation in the 1950s that was energized by the construction of hotel towers designed by important New York architects, university lectures by visitors like Walter Gropius, the flow of international design publications, and the training in American colleges received by many of the island’s architects. In successfully synthesizing Cuba’s past and present the Pérez Farfante house demonstrated that it was possible for the island’s architects to be true to progressive ideals while being inspired by the core values of Cuba’s traditional architecture. In other words, it was possible to be of the modern world while remaining essentially Cuban—a concern that has been central to the island nation since its inception.

By Hermes Mallea

Photos by Adrian Fernandez

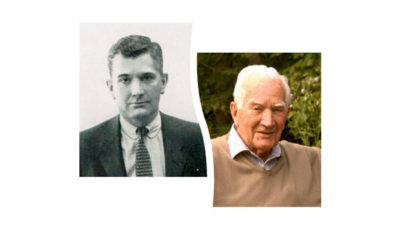

Hermes Mallea, a Cuban-American architect is the author of The Great Houses of Havana: A Century of Cuban Style, published earlier this year by Monacelli Press.