Design

Fall 2011

Roll over André LeNôtre, and tell Gertrude Jekyll the news. As evidenced by Futurescapes: Designers for Tomorrow’s Outdoor Spaces, the gardens of the twenty-first century will bear scant resemblance to the precise geometries of the former’s designs nor to the latter’s almost painterly flower-borders-and-vistas approach. This book offers a survey of the work of fifty contemporary landscape architects and landscape design firms, several of which have already garnered an international reputation. There’s Piet Oudolf, the Dutch leader of the “New Perennials” movement; London-based Charles Jencks; and Patrick Blanc, a pioneer in the idea of vertical gardens. But the book’s real pleasure is the revelation of lesser-known, up-and-coming landscape design talents. These include Landscape India, a company that applies ordered, modernist principles to the classic perfumed gardens of the subcontinent. At the other side of the spectrum, there is England’s Sheffield School design group, which seeks to create gardens with wildly mixed florals in an attempt to disguise the presence of the human hand. Or there is Milan’s Patrizia Pozzi, who in her public spaces reinterprets the rigor of LeNôtre’s flourishes in stylish, even sexy, layouts. The book suggests that the future of greenery is rosy indeed.

Futurescapes: Designers for Tomorrow’s Outdoor Spaces by Tim Richardson. Thames & Hudson, 352 pages, $60

One of the two introductions to this book quotes a 1934 article by P. Morton Shand that appeared in Architectural Review: “The two fields in which the spirit of our age has achieved its most definitive manifestations are photography and architecture …. Without modern photography, modern architecture could never have been.” Shand’s premise may be arguable, but his conclusion is sound. Paintings and sculptures can be brought to the public via exhibitions, but buildings are not a moveable feast. From Edward Steichen’s ethereal 1904 image of the Flatiron Building to the pictures taken by today’s talents such as Thomas Struth, photography has been the medium through which most people have experienced avant-garde architecture. Le Corbusier & Lucien Hervé: A Dialogue Between Architect and Photographer documents a fifteen-plus-year association between the great theorist of twentieth-century structural art and a cameraman with a special sympathy for his structures. The book is laid out with Hervé’s carefully-sequenced contact-sheet photos from groundbreaking to completion of some of Le Corbusier’s most renowned buildings. Apart from Frank Lloyd Wright, I speculate, Le Corbusier has had more ink spilled about his work and ideas than any other modern architect. This book is a worthy addition to the Corbu library.

Le Corbusier & Lucien Hervé: A Dialogue Between Architect and Photographer by Jacques Sbriglio. Getty Publications, 296 pages, $74.95

Wallace Neff was the “starchitect” of Los Angeles in the early years of the twentieth century. His métier was Spanish colonial revival haciendas, though he was best known for the 1920 residence dubbed “Pickfair,” designed for Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks in Beverly Hills. But beyond his work for the glamorous set, Neff spent years hatching a scheme for low-cost, easily-built, and sturdy shelter for those of modest means. In the early 1940s he unveiled a plan for what he fondly referred to as “bubble houses.” As engagingly explained in No Nails, No Lumber: The Bubble Houses of Wallace Neff, to build a bubble house, first a foundation was laid, then atop that a giant rubber balloon was placed. After the balloon was inflated, it was sprayed with gunite—a lightweight concrete. The gunite sets, the balloon is deflated and removed, and voila! You have a house. (Neff spent years perfecting a gunite mixture that would be durable, load-bearing, and well insulated.) Only one bubble house in the United States is still extant. Neff’s design was much better received elsewhere in the world, and whole communities of bubble houses are still happily in use in regions as disparate as Portugal, St. Thomas in the Virgin Islands, and Angola.

No Nails, No Lumber: The Bubble Houses of Wallace Neff by Jeffrey Head. Princeton Architectural Press, 176 pages, $24.95

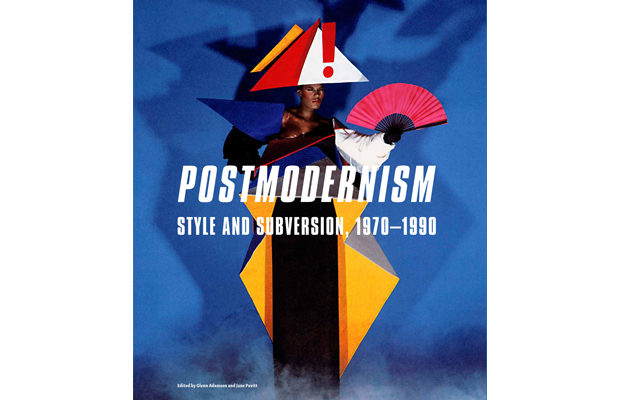

Something weird happened culturally starting in the 1970s and lasting through the 1980s. While punks embraced anarchy, members of the creative classes made their own rebellion. They called it “Postmodernism.” Architect Philip Johnson abandoned Bauhaus purity and designed a Manhattan office tower topped with a Chippendale split pediment roof; his peers Michael Graves and Robert A. M. Stern came to the fore with blithe takes on classicism. As they explain in Postmodernism: Style and Subversion, 1970—1990, the catalogue for an exhibition that opens at the Victoria & Albert Museum on September 24, the curators believe the fact that postmodernism is the subject of a major museum survey is ironic: the movement was “antagonistic to authority. Postmodernism’s territory was meant to be the periphery, not the centre. Its artefacts resist taxonomy.” Which is not to say that postmodernism is not explainable. In the realms of design and architecture, it was an assault on convention. Modernism, by the 1970s, was stale and predictable—black box buildings, black boxy furniture. Architects like Graves and Stern, and, in Italy, design groups such as Studio Alchimia and Memphis Milano, rebelled. They had a point to make. And if their over-the-top designs can seem odd today, they made their statement heard.

Postmodernism: Style and Subversion, 1970—1990 ed. Glenn Adamson, Jane Pavitt. V&A Publishing (distributed by Abrams), 318 pages, $65