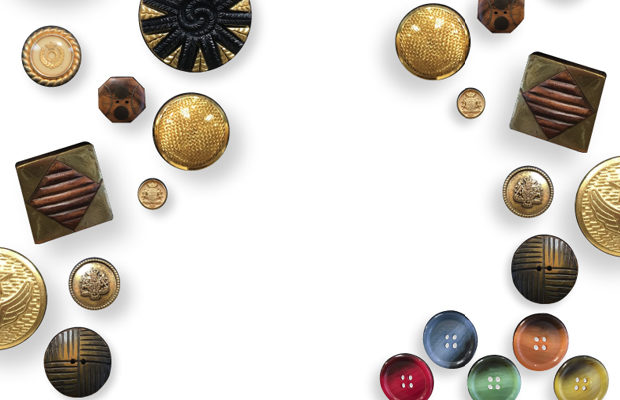

COURTESY LOU LOU BUTTONS/NICOLE ANDERSON PHOTOS

COURTESY LOU LOU BUTTONS/NICOLE ANDERSON PHOTOS

Feature

Extra Ordinary: Pushing Buttons

AT FOUR, I LANDED MY FIRST (UNPAID) job, conductor of my nursery school rhythm band. If I had known then what I know now— that conductors wield considerable power and can make a lot of demands—I’d have insisted on including my favorite percussion instrument: my mother’s button box. It was in my view more interesting and versatile than wood blocks or a triangle or bells.

LIONEL ALLORGE PHOTO/WIKIMEDIA.ORG

My mother kept a hinged metal box, not much bigger than a pack of cards, in the top drawer of her sewing table. It was full of all kinds of buttons: plastic, wood, mother-of-pearl, bone, leather, brass, silver, pewter. I loved to shake it at a variety of speeds, and learned that by taking some buttons out, or making various combinations of sizes and materials, I could alter the sound. In retrospect, I realize that the button box was, in addition to its many other virtues, tunable.

By five, I was a woman of the world and had lost interest in the button box and buttons. I was seventeen before I understood the error of my ways. My sister, a newly minted university graduate with an entry-level job, bought a blue wool sleeveless dress. There was nothing noteworthy about it until she sewed three small brass buttons on the front. They were from the uniforms—circa 1900—of a New York City police officer, a firefighter, and a railroad conductor.

Suddenly, the plain-Jane dress was both a knockout and a conversation piece.

Those buttons served the same purpose as their antecedents had for thousands of years: ornamentation. Buttons had very little practical application until an unknown genius (safe bet: a woman) invented the buttonhole. Though its origins are probably Persian, the buttonhole first took hold in thirteenth-century Germany. Wardrobe malfunctions, which presumably date to the time of cave people, became, if not a thing of the past, certainly no longer commonplace. Buttons, those simple, easy-to-attach fasteners, suddenly had an everyday function, holding things up or in, over or out, and made garments more adaptable, too. Button up to stay warm, undo a few to cool off (or seduce).

PEACH STATE BUTTON CLUB/WIKIMEDIA.ORG

Over time, buttons became both more and less elaborate, and, with the Industrial Revolution, of course, cheaper. Perhaps the most remarkable variety—ranging from the gorgeous to the slightly creepy—is the “habitat” button of the eighteenth century, which preserved and displayed, say, a flower or a lock of hair.

The button is safely back in my heart as an object of desire and affection. If you doubt its appeal, remember this: no one ever says that something is “cute as a zipper”— or cute as Velcro or a snap or a hook and eye. But “cute as a button”? There’s nothing better.