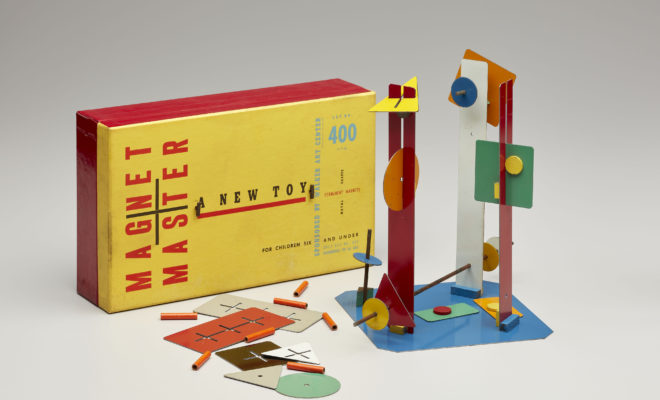

Magnet Master 400, 1947, designed by Arthur A. Carrara. MILWAUKEE ART MUSEUM, PURCHASED WITH FUNDS FROM THE DEMMER CHARITABLE TRUST / JOHN R. GLEMBIN PHOTOS

Magnet Master 400, 1947, designed by Arthur A. Carrara. MILWAUKEE ART MUSEUM, PURCHASED WITH FUNDS FROM THE DEMMER CHARITABLE TRUST / JOHN R. GLEMBIN PHOTOS

Design

Design at Play

THE WORK OF MID-TWENTIETH-CENTURY American designers Charles and Ray Eames, Alexander Girard, Isamu Noguchi, and Eva Zeisel is widely known, but perhaps less so is the role that play had in their designs during an era of rapid change. The exhibition Serious Play: Design in Mid-century America, opening at the Milwaukee Art Museum on September 28, explores playfulness as a catalyst for creativity. Designers of the time believed that play could, and should, be taken seriously; as curators of the show, we assert the same. Author Steven Johnson noted in Wonderland: How Play Made the Modern World (2016): “The pleasure of play is understandable. The productivity of play is harder to explain.” The two hundred–plus works in this exhibition are organized into three themes—the American home, child’s play, and corporate approaches—that help elucidate the significance of play.

Swing-Line toy chest, 1952, designed by Henry P. Glass and manufactured by the Fleetwood Furniture Company. MILWAUKEE ART MUSEUM, PURCHASED WITH FUNDS FROM THE DEMMER CHARITABLE TRUST / JOHN R. GLEMBIN PHOTOS

During the postwar years the home emerged as a space in which architects and designers explored new ways of living. For example, with a booming economy, Americans acquired more goods, and storage became a key issue. The Eameses, Girard, and George Nelson, among many others, created storage units of various types that encouraged improvisational and imaginative decorating. (Self-expression through the choice and placement of objects was central to individualization in an era of men in gray flannel suits.) Whimsical product designs, such as Erwine and Estelle Laverne’s Jonquil chair, were considered imaginative solutions for crowded dwellings: the Lavernes’ transparent furniture virtually disappeared! Similarly, Irving Harper, who worked for George Nelson Associates, designed some of the most important, recognizable, and playful clocks of the twentieth century for the Howard Miller Clock Company. In the Kaleidoscope clock, the “arms” of the hour and minute hands— represented by a reddish circle and short black line—are transparent, creating a floating effect as the hands rotate. Harper then surrounded the polygonal face with six mirrors to create a kaleidoscopic effect. Eva Zeisel offered consumers not only amusing objects but also more playful ways of engaging with mass-produced ceramic tableware. Her Town and Country line put playfulness into the hands of the user: thirty-four different pieces came in twenty-three different color combinations, so that the ways in which the pieces interacted with one another depended on how the consumer, rather than the designer, arranged them.

Isamu Noguchi’s Play Sculpture at Moerenuma Park in Sapporo, Hokkaido, Japan. © THE ISAMU NOGUCHI FOUNDATION AND GARDEN MUSEUM, NEW YORK / ARTISTS RIGHTS SOCIETY (ARS), NEW YORK

Designing for children was also serious business. In her book Designing the Creative Child: Playthings and Places in Midcentury America (2013), Amy F. Ogata established that the educational toys prized at the time not only had pedagogical applications but were also examples of good design. This exhibition considers architect-designed toys—including ones by the Eameses, Arthur Carrara, and Anne Tyng—that were marketed specifically for their ability to develop creative young minds; the exhibition also examines the small-scale furniture that was expressly designed for children’s spaces and their activities, such as playing with building toys. Some of the liveliest children’s furniture was created by Chicago architect Henry P. Glass, who designed the Swing-Line series for the Fleetwood Furniture company in 1951. Glass’s toy chest, with its four colored bins that swing outward, would have handily held many of these experimental toys. Ideas about children’s development in the context of play extended to the outdoors as well. In 1953 the educational toy company Creative Playthings added a Play Sculptures division, for which architects and designers created sculptural playground equipment that was more open and imaginative than earlier examples. Similarly, Isamu Noguchi designed playgrounds and play structures to stimulate creative activity as a way for children to learn and participate in the world.

Pleated Star wall clock, model 2224, designed by Irving Harper of George Nelson and Associates in 1955 for Howard Miller Clock Co. COLLECTION OF JAY DANDY AND MELISSA WEBER

The impetus for play was not restricted to domestic and children’s settings alone: segments of corporate America explored new avenues for cultivating distinctive brand identities. Graphic designers such as Paul Rand found ways of making images and words jump off the page and into the hearts and minds of the American public. In 1956 Alcoa initiated the Forecast program, which commissioned designers to employ aluminum in creative ways to “inspire and stimulate the minds of men.” The results evoked the era’s spirit of pure, unadulterated originality. And in the mid-1960s, Alexander Girard, known for his whimsical graphic designs, juxtaposed Latin American folk art and gridded structures for the Braniff International VIP lounge, demonstrating that even a complex corporate identity can mix playfulness with luxury, and allow for some plain old fun.

Serious Play: Design in Midcentury America is on view at the Milwaukee Art Museum from September 28 through January 6, 2019, and at the Denver Art Museum from May 5 through August 25, 2019.