Courtesy Wright

Courtesy Wright

Design

Delving Deeper

A LAMP BY ICO PARISI GOES FULL SPECTRUM

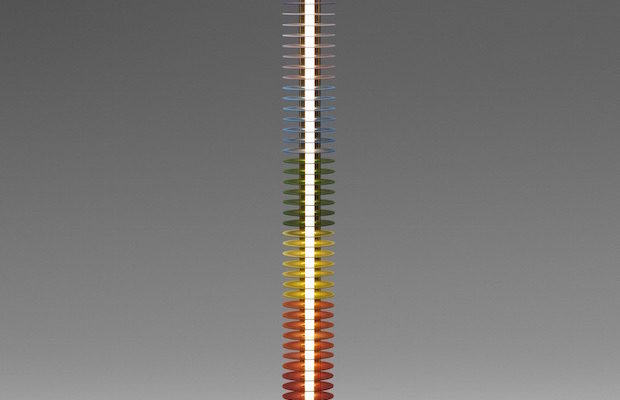

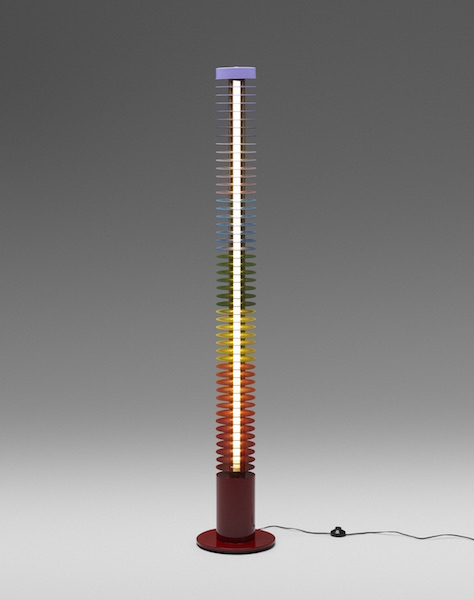

LOT 307 Wright Design sale, June 8, 2017: Iride floor lamp by Ico Parisi, manufactured by Lamperti, 1970. Estimated at $7,000–$9,000, the piece sold for $23,750. Some reasons for the high price:

Courtesy Wright

ITALIAN RENAISSANCE MAN

Filmmaker, architect, photographer, painter, designer—Ico Parisi was a true Renaissance man. In the early 1930s, he trained in construction while simultaneously studying art with his father, who was a painter. In the second half of that decade, Parisi cofounded two architectural groups—Alta Quota and Gruppo Como—both of which became laboratories for his exploration of architecture, art, and design, and his lifelong interest in their interplay. A true modernist in this regard, he once said, “Architecture may only be brought into synthesis with other arts if architects live and breathe elbow-to-elbow with painters and sculptors.” While he completed commissions for architecture and design, such as the State Library in Milan in 1947, it was not until 1950 that Parisi formally completed his architectural studies at the Athenaeum Architecture School in Lausanne, Switzerland, providing him with opportunities to work fluidly with other creators in art and design disciplines that would later define his work. Through his diverse and prolific output, Parisi contributed to a twentieth-century, appropriately Italian, renaissance in design.

COMING TO COMO

In the late 1940s, Parisi cofounded Studio la Ruota in Como, Italy, with his wife, Luisa, also an architect, with whom he frequently collaborated, and they remained most active there for the duration of their careers. They secured a number of residential commissions for villas near Lake Como, including Casa Carcano in Maslianico, completed in 1949, which ignited wide interest in Parisi’s furniture design, specifically. Pieces from it were exhibited in Milan and heralded in Domus magazine, a publication created by Parisi’s friend and fellow designer—and admiring promoter—Gio Ponti. In the realm of furniture, Parisi produced an eclectic oeuvre that, when looked at empirically, could believably be selections from the work of multiple designers. But such variety is a testament to the fervid experimentation and collaboration in materials, form, and aesthetics that earned him a name.

LAMPADA POP

Even in a career of broad interest and examination, the Iride lamp would appear to be a departure from Parisi’s earlier popular work. Its aluminum and steel structure diverges from his familiar furniture in wood, such as his sinuous tables and organic Egg chair from the 1950s, with its exposed, spindly legs. Yet the lamp, with colorful discs rippling up and down its slender frame, conveys a characteristic sense of movement and functional transparency. As Michael Jefferson, senior vice president at Wright, observes, it “echoes of the structural rigidity of building—columns, windows, shelving systems with notches, modularity. It fits with his other experimentation.” In such a fixture, Parisi’s fascination with the integration of art, architecture, and design is synthesized in a functional yet sculptural piece, referencing its built surroundings in verticality and durable materials. But one quality in particular cannot be understated in the lamp’s appeal: its aesthetic amusement. As a cylindrical spectrum with a lightning rod shot through it, the Iride lamp presents an irresistible pop art sensibility—a “punctuation mark!” as Jefferson appropriately describes it.

“Italian lighting is on an upward swing,” Jefferson adds. He attributes this popularity to a reverence for the radical design that emerged between 1968 and 1972 and accom- panying lifestyle shifts. Or, considered more simply, “It’s easy to live with—it’s functional sculpture.”

A PRICE FOR IRIDE

Parisi’s work (and often that created with Luisa) is frequently offered at auction at enviable estimates and produces typically healthy sales, with some exciting spikes on pieces over the years. In this design sale, Wright aimed to present a focused selection in an effort to concentrate buyers’ bidding. The lamp—coming from a private collection in the Americas—was thus part of a smaller sale that overall sought to highlight rare, truly exceptional pieces. Jefferson commented that after a boom in the market about a decade ago—thanks to a pre-recession economy and a new exposure to specialty interests via the Internet—the design market is adjusting as collectors are taking a second look at design and reconsidering how affordable it can be. While collectors become more discerning and calculating, the market acclimatizes, and the numbers steady accordingly. “We don’t want to get ahead of ourselves in estimates,” Jefferson says, citing what he calls “tease estimates” that skew conservatively based on precedent, such as the estimate for this lamp. Other models of the Iride lamp have recently been offered at auction, including a similarly colorful companion in 2014 and a monochromatic black and gray edition in 2015. The colorful version sold comfortably within the estimate of the one in the recent Wright sale. “We had a lot of the attention from collectors and buyers,” Jefferson reported on the sale, with its sharp focus helping to drive prices. Such focus, it seems, that the piece achieved a world record for the model. The rare Iride went to art collectors who shop the art and design markets for the most notable pieces—and this lamp’s special flair certainly put them over the top for this sale.