Feature

Czech and Baroque: Borek Šípek

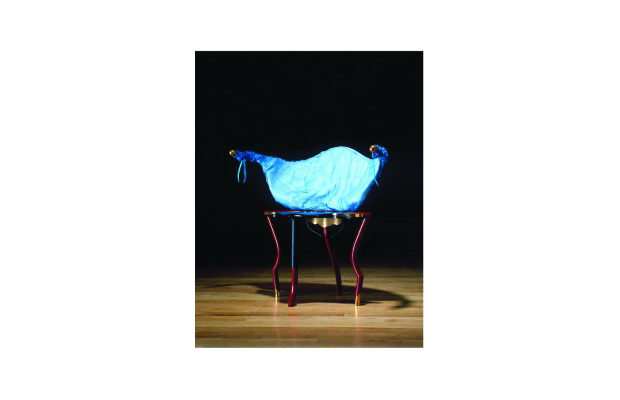

Šípek’s whimsical Bambi chair of 1983 is named for his wife, a ballerina.

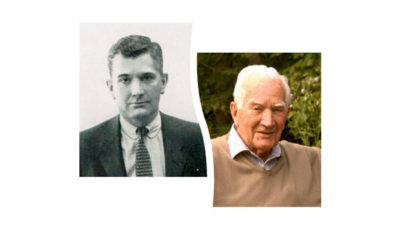

Borek Šípek in the garden of his cottage near Novy Bor, Czech Republic, a center for Czech glassmaking.

In Prague all things point to the castle. Ancient, huge, and visible from nearly every part of the city, Prague Castle is the seat of the Czech Republic. Borek Šípek left his mark on this icon of Czech history as the court architect during the presidency of his friend Václav Havel, from 1993 to 2003. But the Czech native son is also a prolific glass artist and designer of furniture, porcelain, and silver objects.

Today glass and architecture are the sixty-three-year-old Šípek’s focus. Glass, of course, is part of the Czech national artistic legacy, and Šípek’s fellow Czechs, as well as museum curators and collectors, place him among the most skilled glass artists in the world. But a vast body of work preceded that.

Šípek gained renown in the design world in the late 1980s and early 1990s with highly referential furniture and the functional objects he designed for Driade, Vitra, Neotu, Sèvres, and Steltman. David McFadden, chief curator of the Museum of Arts and Design in Manhattan, points out that Šípek “always experimented with a wide range of materials and techniques. While his pieces are clearly contemporary, they contain references to the history of ornament and decoration that give them presence, depth, and often whimsy.”

Among them are furniture with folkloric references, baroque impulses, and a good dose of humor, such as the wicker chairs Šípek designed for Driade that were as personal as they were functional. Then there was his unforgettable Bambi chair—an enticing feminine seat on fawnlike legs. Or the wood and terrazzo Steltman desk for Steltman Galleries in Amsterdam; the desk has five legs and the terrazzo top has black granite inlays to indicate the position of those legs, just another witty gesture at once subtle and obvious.

Craig Miller, the twentieth-century design expert who is senior curator of design arts and director of design initiatives at the Indianapolis Museum of Art, has known Šípek since the mid-1980s. “I was working at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and went to visit him in Amsterdam,” said Miller. “There was enormous creativity in this period by a group of younger postmodernist European designers that included Šípek, Philippe Starck, Michelle De Lucchi, and Sylvain Duibuisson. Šípek was over the top, rich, original. He may have been a little exotic for Americans’ more conservative taste in furniture. In the 1990s he began to work more and more in architecture and, of course always with glass.”

Under Miller’s direction, the Denver Art Museum held a solo exhibition of Šípek’s work in 1996, Borek Šípek: Auratic Architecture and Design, which included sixty examples of his ceramics, metalwork, furniture, glass, and architectural models. Other solo museum exhibitions have been at the Musée des Tissus et des Arts Décoratifs in Lyon (in 1987); the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam (1991); the Vitra Design Museum in Weil am Rhein, Germany (1992); and the Národní Museum (National Museum) in Prague (1998).

Šípek was born in Prague in 1949. His parents died when he was young and he was adopted by Rene Roubicek and Miluse Roubickova, glass artists now in their nineties whose work is in collections and museums throughout the United States and Europe. Tina Oldknow, curator of modern glass at the Corning Museum of Glass in Corning, New York, observes that Šípek’s style in blown glass was influenced by these pioneering artists, especially Miluse Roubickova. “Šípek’s work is colorful, fun, with a joie de vivre that is not always seen in Czech glass,” Oldknow says.

Marketa Vejrostova, the curator of glass at the Moravian Gallery in Brno—the second largest museum in the Czech Republic—concurs, praising Šípek’s glass for its imagination, playfulness, and colors. The compotes decorated with glass fruit toppling over the rim are, simply, classics.

Glass is not necessarily a solo art, or craft. Šípek has worked with the same master craftsman, Ivan Kubela, since 1986. Indeed, Milan Hlaves, a senior curator at the Museum of Decorative Arts-Prague is quick to point out that Šípek has a special talent for “being maximally able to use the skills of the master craftsmen at the factory and all the characteristics of glass. His is a modern mannerism.”

For all that, Šípek’s education was actually focused on architecture. At fifteen he began four years of study at Prague’s School for Arts and Crafts and then moved to Germany to studyarchitecture at the University of Applied Arts in Hamburg, from which he graduated in 1974. He studied philosophy at the Technical University in Stuttgart and eventually received a doctorate in architecture from the Technical University of Delft. He’s remarked, though, that his study of philosophy was a gift to his architecture, an idea elaborated on in an essay by architectural historian Gavin Keeney called “Šípek is not Šípek” first published in 1996.

Today he is a professor of architecture at the Prague Academy of Applied Arts, a professor of design at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna, and the dean of architecture at the Technical University of Liberec, which is not far from his glass factory in Novy Bor. He travels and works constantly on architectural projects around the globe: private houses in Shanghai, a department store in Tokyo, the Skoda pavilion for the international automobile exhibition in Hanover, Germany, a circular apartment complex in the Dutch city of Apeldoorn, the Opera House in Kyoto. He’s designed hotels and boutiques in Prague. Among the best known is the Hotel Neruda, a convent dating from 1348 that he transformed into a showcase of his own “neo-baroque” (the term he himself uses) aesthetic.

In Dakar he is the chief architect for a memorial dedicated to slavery in Senegal. During the Salone Internazionale del Mobile 2012 in Milan Šípek exhibited with his friend Ingo Mauer at the Spazio Krizia showroom, showing off enormous new pieces including a candelabra and a bowl for flowers.

In Prague, he’s at home in the Mala Strana section of the city, just a ten minute walk from Prague Castle. His office-apartment-studio occupies a rather small L-shaped space in a corner of the fifth floor of an ancient courtyard building (the foundation is some seven hundred years old, the building itself about four hundred). On the ground floor he has a gallery, open by appointment. There is a small retail shop for his glass across the Vetava River, between the Museum of Decorative Arts and the Old Town Square.

In the living area of the apartment Šípek generally keeps eight of his own chairs around the dining table—no two alike. There is also a somewhat incongruous set of All-Clad cookware that has made its way to his fifth-floor walkup from southwestern Pennsylvania; he reports that cooking is a favorite pastime and he has designed and owned three restaurants in Prague. On one wall of the room hangs Absolut Šípek, a photograph by Jan Saudek of a lithe and beautiful blond woman swathed in a revealing veil next to a tall piece of Šípek’s glass art.

A new eight-piece collection called Blacks is about to be released from the factory in Novy Bor. Asked for his inspiration for the collection Šípek answers simply, “I wanted to try something using black.” Even now, he clearly does not take himself too seriously.

A Baroque Soirée: by Borek Šípek is on view through October 13th at Industry Gallery