Joseph Hu Photo

Joseph Hu Photo

Design

Curator’s Eye

We asked curators of leading twentieth-century and contemporary design collections to discuss one object that they feel is particularly noteworthy. Here is a gallery of their choices.

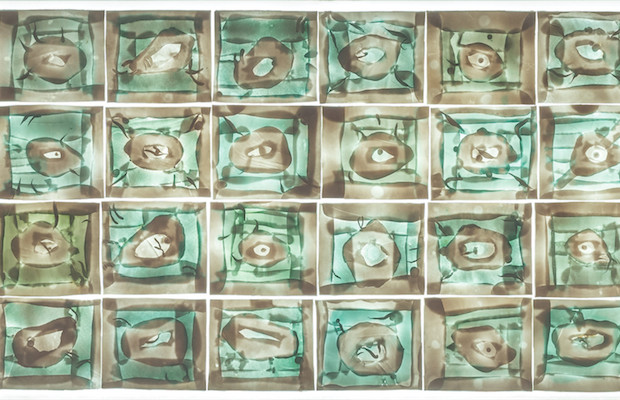

Pillow Book demonstrates how Lee conflates her knowledge of language, storytelling, and translation

Helen Lee (1978–) PILLOW BOOK, 2015. Glass. Minnesota Museum of American Art, Purchase, Acquisition Fund

HELEN LEE FELL INTO A PERIOD of deep grief after the death of her mother in 2011. During that time she spent a disproportionate amount of time sleeping. Her relationship with sleep became fluid, with very little differentiation between being awake and dreaming. When Lee talked about her experiences with friends, they shared their dreams about her, recalling funny and sometimes touching stories. She was fascinated by the idea that, while she spent her time sleeping, a version of herself was making guest appearances in her friends’ dreams. Of one such event, she recalled that a friend wrote: “You had been in my dream the night before you sent this email. You were visiting me somewhere and wanted to leave and go to bed early because you were tired. There were other people around.”

Pillow Book was inspired by this difficult time of transition in Lee’s life, but it also beautifully demonstrates how she conflates her knowledge of language, storytelling, and translation—interests that have been at the core of her glassmaking for many years.

Lee used a photosensitive sandblast resist technique to engrave eighteen transcribed dreams into individual sheets of glass, and then filled each letter with enamel. In a time-consuming process, she kiln-fired groups of these glass sheets together. She then annealed the whole piece for fifteen days. Once it cooled, the work was carefully carved and polished, using a hand grinder.

The final shape closely resembles that of a Chinese ceramic pillow. These domestic objects, some of which were elaborately molded and decorated with intricate patterns, have been found in tombs as well. It is this dual purpose that has long fascinated Lee and why Pillow Book so elegantly implies temporary as well as eternal sleep. Since dreams are often filled with complicated narrative arcs with rapidly shifting actors and scenes, they can be difficult to put into words, slipping from memory as soon as we wake up. The stories embedded in Pillow Book are visible and held in place, but they remain indecipherable, since they are impossible to read through successive layers of clear glass.

Christopher Atkins

Curator of Exhibitions and Public Programs

Minnesota Museum of American Art, Saint Paul