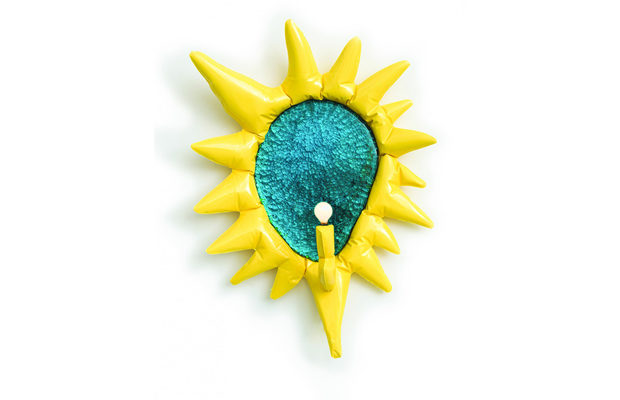

Misha Kahn’s Large Yellow Mirror/Sconce from his Saturday Morning series, 2013, is made of resin, vinyl, glass, and foil.

Misha Kahn’s Large Yellow Mirror/Sconce from his Saturday Morning series, 2013, is made of resin, vinyl, glass, and foil.

Feature

CROSSING THE BRIDGE

IN BROOKLYN’S ONCE INDUSTRIAL neighborhoods, many strung along the waterfront, a number of warehouse buildings have been converted into studio space, beckoning artists and designers to such areas as Bushwick, Red Hook, Gowanus, Sunset Park, and the Navy Yard. Three designers—Misha Kahn, Ian Stell, and Betil Dagdelen—have found a home in Brooklyn. While they toil and create on one side of the Bridge, their work has taken center stage at galleries across the East River in Manhattan.

IN DESIGNER IAN STELL’S WORK, ACTION is at the forefront, from the swift movement of the joinery to the interaction between the user and object. More often than not, a chair can be relatively static in its form and function. It might be able to recline or retract, offer a limited range of motion, but rarely, is it able to mutate so nimbly in shape and scale as Stell’s designs: take for instance, his Bookish chair, which resembles the splayed pages of a book as it opens and closes. The transformative nature of his furniture mines or even obliterates the very notion of an object’s given purpose, offering up new perspectives and possible uses.

“I’ve always been inspired by the anonymous provenance of functional objects. For example, I think of chairs as a palimpsest shaped by many hands and minds through millennia—in a state of perpetual mutation,” Stell says. “Along with its prescribed purpose, there is ritual. And there is ‘misuse,’ which is a seed of the new.”

Ian Stell’s Bookish chair, 2012, is composed of forty interlocking sections—laminations of aluminum and wood—and evokes the splayed pages of a book.

At Patrick Parrish gallery in TriBeCa, Stell pulls one side of his Austrian Loop chair, and the wood seamlessly expands like the bellows of an accordion. The movement is only one part of the intrigue; on a more micro level, it is the feat of orchestrating the latticed wood so meticulously so as not only to shift but to visually come together as one cohesive whole in much the same way as instruments do in an ensemble.

Made of brass pivots and maple wood, the piece is inspired by the tête-à-tête conversation chairs fashionable in France in the eighteenth century. Stell conceived the chair based on the pantograph, a device that he describes as “a seventeenth century precursor to the copy machine,” which uses a hinged parallelogram configuration to “accurately transmit and multiply motion.” This is part of a larger series in which he explores the full breadth of the pantograph invention, culminating in the Big Pivot, a large ebonized white oak table that can easily contract into a smaller desk, and the equally expandable Sidewinder(s), an ebonized white oak and dyed curly maple side table.

These intricate structures come to life through a multi-step process that employs both computer-aided design software and his own handiwork, requiring some trial and error along the way. “I usually try to bring an improbable idea to a tangible realization, and this often leads in unexpected directions,” Stell says. “Of course when a project begins to shift from virtual to palpable, there is always a lot of troubleshooting, and I learn the most at these moments. The knowledge gained doesn’t merely make me a better fabricator, it’s an invaluable ingredient in the development of new ideas.”

A born and raised New Yorker, Stell admits his trajectory into the design field was a circuitous one that began at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, where he studied painting and sculpture. When he returned home, he launched several bars and a restaurant in Manhattan. “My partners and I did everything in the beginning, and it fell to me to ‘design’ these venues. I put design in quotes here as I was a sculptor with no formal training in industrial design and fabrication,” he says. “Through this experience, I developed a passion for making objects that people can use and touch.” Self-taught, he decided to take his skills one step further, and entered the graduate program in furniture design at the Rhode Island School of Design. After years of being out of school, it felt like “an enormous leap of faith.” But there he was able to further hone his craft and test out ideas. The risk was certainly worth it.

When he returned home to New York, Stell’s work quickly gained traction. Less than two years after graduating from RISD, he had his first solo show at Matter, landed on Sight Unseen’s 2014 Hot List as one of twenty-five “key players” in the American design field (so was Kahn)—and was presented in the online publication’s curated show Sight Unseen OFFSITE. He now creates most of his work in his studio in Red Hook.

Recently, his piece Diagint, composed of two crisscrossing flights of stairs, was installed at Spree Studios, a creative venue for artists on the site of a repurposed public swimming park on the Spree River in Berlin. This work, much like his Pantograph series, is an exploration of a structure we use every day. Stell questions and re-imagines the given design: a special hinge configuration allows for each flight to pivot, thus creating a four-way passage. With two new folding staircase designs on the horizon, Stell continues to challenge the quotidian objects and architecture that fill our lives, allowing them to take on new and unexpected forms, and profoundly change the way we relate to our surroundings.