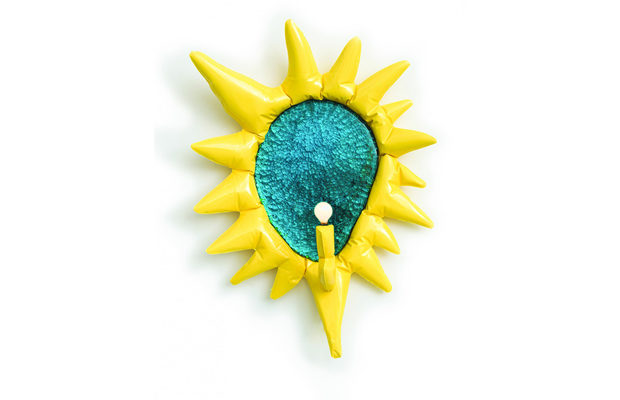

Misha Kahn’s Large Yellow Mirror/Sconce from his Saturday Morning series, 2013, is made of resin, vinyl, glass, and foil.

Misha Kahn’s Large Yellow Mirror/Sconce from his Saturday Morning series, 2013, is made of resin, vinyl, glass, and foil.

Feature

CROSSING THE BRIDGE

IN BROOKLYN’S ONCE INDUSTRIAL neighborhoods, many strung along the waterfront, a number of warehouse buildings have been converted into studio space, beckoning artists and designers to such areas as Bushwick, Red Hook, Gowanus, Sunset Park, and the Navy Yard. Three designers—Misha Kahn, Ian Stell, and Betil Dagdelen—have found a home in Brooklyn. While they toil and create on one side of the Bridge, their work has taken center stage at galleries across the East River in Manhattan.

Fantastical in both concept and appearance, Kahn’s works straddle the line between art and design, and the real and imagined

NEARLY EVERY CORNER, WALL, AND AVAILABLE SURFACE in artist-designer Misha Kahn’s Bushwick studio is in full use, brimming with objects, tools, and machinery that are vital to the process of creating his amorphous, and often candy-colored pieces of furniture. These works, some completed and others in a metamorphic state, are speckled throughout the space. Fantastical in both concept and appearance, they straddle the line between art and design, and the real and imagined. The congealed-like texture of the materials and the sinuous forms make these static objects appear to be in motion, as if figures in an animated film.

At the time of this visit Kahn is in the midst of preparing for his first solo show at the Friedman Benda gallery in New York City, slated to open at the end of February. Calling it, Return of Saturn: Coming of Age in the 21st Century, Kahn wants the show to be as “eclectic” as possible. “I probably shot myself in the foot, but from the get-go I didn’t want there to be any series. So you walk in and it feels kind of like it is a group show,” he explains. “It’s tied together, though, with all these motifs from a little bit of my family’s basement and also just what I imagine America’s basements feel like, with all these weird secret things we keep. So there are a lot of elements of hoarder culture and nostalgia and extraneous materials.”

Kahn warns these themes will be subtle, and may not be immediately evident to the gallery-goer. This isn’t the first time, however, that he has explored ideas around consumerism and consumption and their impact on American popular culture. In a 2015 pop-up exhibition entitled Mall Girl, organized on the Lower East Side by Gallery Loupe, Kahn looked to such artificial landscapes as malls and roadside attractions to come up with a line of resin jewelry. Much like his sculptural necklaces and bracelets, all of his work—from his Concrete stools to his floor lamps—has a strong tactile pull. They elicit an almost child-like temptation to want to touch the materials, so as to negotiate the intriguing discrepancy between the inflatable, gummy appearance and the compact forms made of cement.

This last year has been a busy one for Kahn. His furniture was shown at FOG Design + Art, PAD London, and Collective Design in New York, and was also featured in the Museum of Arts and Design’s NYC Makers exhibition. More recently, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston purchased one of the large basket-cum-lighting installations he made in Swaziland; it hangs from the ceiling like a series of beehives with enclosed illuminated colored glass suspended at different points.

Born in Duluth, Minnesota, Kahn grew up sewing, and expected he would end up in apparel, but on a fortuitous whim, he decided to apply to the furniture program at the Rhode Island School of Design instead. There, he developed his own approach, using sewing machines and casting methods, in part because the woodshop was always in high demand. The program had this “other room” that was rarely used since it had few tools, but it was in this space that Kahn found a reprieve and the opportunity to explore different materials and processes. This resourcefulness served him well when he moved to Brooklyn. “I started dealing with cement just because it is very cheap, and I was in a tiny studio in the Navy Yard, and this way the molds are fabric or vinyl so they just squish into nothing so it is efficient,” he says.

Experimentation and fun are at the heart of Kahn’s work, which seems to run counter to the sometimes all-too-serious practice of furniture-making these days. His openness to the unforeseen adds an element of unpredictability, and best of all, a sense of humor, as embodied in his transparent, inflating chandelier or his resin and vinyl mirror shaped like a comic-book starburst.

“I feel like I show up in a scenario where I think, what is the most fun thing I can do—and what is on the edge of possible?”