PRIVATE COLLECTION

PRIVATE COLLECTION

Exhibition

Creative vs. Corporate

We believed that once all business embraced the notion of design as a function of management, all of us would be employed to produce beautiful products (…). But it didn’t turn out the way we thought. Sure enough, Big Business embraced design, and promptly turned it into a commodity.

Saul Bass, American graphic designer (1920–1996)

From: Designer Interviews in Aspen, no. 4: Saul Bass, 1986

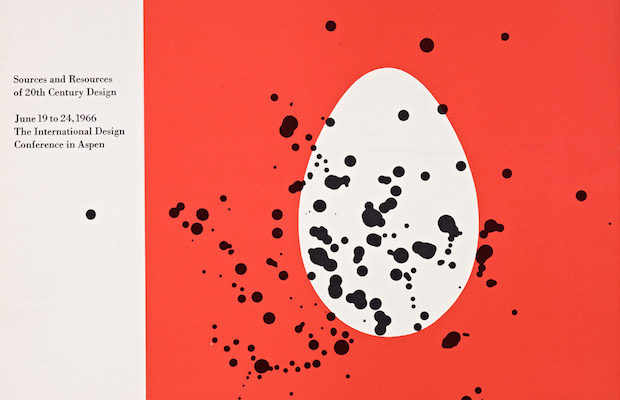

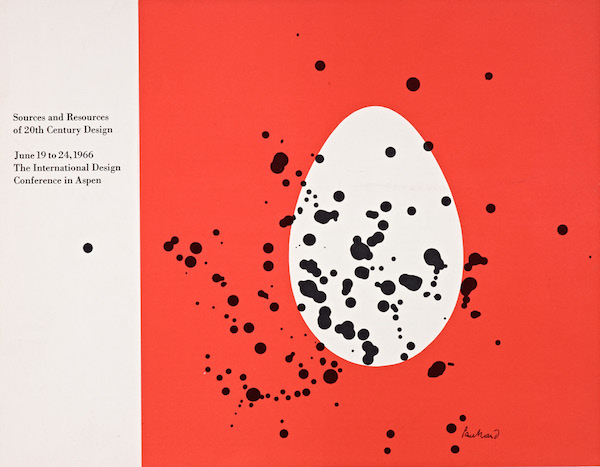

THE CANTOR ARTS CENTER at Stanford University presents the giants of mid-century design—with a twist—in Creativity on the Line: Design for the Corporate World, 1950–1975 through August 21. While displaying some of the best-known works of Eliot Noyes, Paul Rand, Charles and Ray Eames, Ivan Chermayeff, and others, the exhibition also delves into their conflicted feelings about creating work for large corporations. Were they selling out? And the corporations were equally in turmoil over whether or not the designers were moving in a direction that was a little too far-out for comfort. The idea for the exhibition came to Wim de Wit, adjunct curator of architecture and design, while doing research in the archives of the International Design Conference in Aspen (IDCA). Through careful reading and re-reading of the proceedings of IDCA, he discovered that even though the subject of the conference differed from one year to the next, there was a recurring underlying theme. “Especially in the 1950s and ’60s,” de Wit explains, “there was the question: are we as artists selling out to commerce by working with corporate managers who tell us that market research indicates that a certain design will or will not sell?”

Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, Gift of Daniel Ostroff

The exhibition catalog Design for the Corporate World: 1950–1975, goes into depth about the ambivalent feelings that both the designers and corporate managers voiced during this era in essays by de Wit and by Louise A. Mozingo, professor and chair of landscape architecture and urban planning at UC Berkeley. Greg Castillo, associate professor of architecture at UC Berkeley, focuses on the IDCAs of 1963 and 1970, and the book concludes with an overview of design education at Stanford in the postwar era by Steven McCarthy, design professor from the University of Minnesota.

The exhibition takes a somewhat different path, first explaining in introductory wall text why post-WWII corporations wanted to hire graphic and product designers to create the unique identities that they needed to compete in business at that time. The show moves on from German companies of the Cold War era, to Olivetti and the Container Corporation of America, the IDCA conferences, to the creation of graphic identities, and ends with product design. Since the ambivalence felt by both designers and marketing managers isn’t apparent in these displays, an entire wall is covered with quotes on the topic.

De Wit wants visitors to take away the idea that although there was a mutual dependence between designers and corporate managers in the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s, there was also suspicion on both sides. “Corporate design may be financially advantageous,” says de Wit, “but a designer as an artist does not want to be considered someone who works for money only. The fear of selling out to commerce is omnipresent.”

Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum, New York