Ron Arad’s studio in North London is filled with his iconic pieces and works in progress, reflecting the breadth of his design projects and his active creative process. EXCEPT AS NOTED, ALL IMAGES COURTESY OF RON ARAD ASSOCIATES.

Ron Arad’s studio in North London is filled with his iconic pieces and works in progress, reflecting the breadth of his design projects and his active creative process. EXCEPT AS NOTED, ALL IMAGES COURTESY OF RON ARAD ASSOCIATES.

Feature

Boundless curiosity

Ron Arad isn't at ease when asked to define the boundaries of his work. “What boundaries?” is his rhetorical response, having comprehensively shown me his studio in North London, a characterful space with a swooping roof and a floor that swells into a wavelike curl. Hidden from the main road and set back from its busy Camden environs by a courtyard, it is approached up a set of narrow stairs and through an unassuming door that might befit a garden shed, only to give way to the elaborate interior.

Ron Arad. Courtesy of Ron Arad Associates.

“A lot of people want to discuss breaking boundaries,” Arad continues. “I think the more you discuss breaking boundaries, the stronger you make them.” He is seated on a sofa made of three soft cylinders, wearing one of his signature hats, though what he is saying is intensely serious. His work, like his manner, strikes a fine balance between maverick and measured. The London-based designer, who was born in Tel Aviv and works internationally, is busy with an assortment of projects that resist any notion of set parameters, ranging from studio work such as public sculpture to designs for industrially produced furniture by Kartell and Vitra. Ron Arad Architects is also developing a number of projects including a high-profile Holocaust Memorial adjacent to the Houses of Parliament in London, in partnership with Adjaye Associates. In other words, the studio might look relatively modest, but its reach clearly outdoes its size.

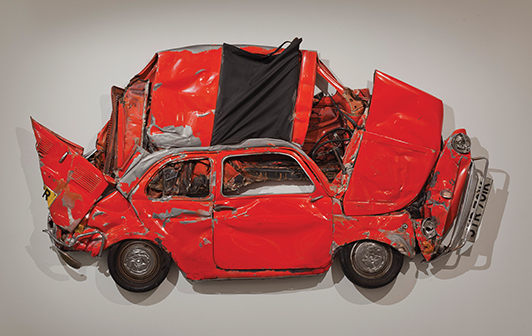

Arad is known for combining industrial design with a more artistic practice. The latter currently includes work for numerous forthcoming exhibitions. One opens this November at Grob Gallery in Geneva and will showcase ten one-off pieces. Another at Gordon Gallery in Tel Aviv, opening in March 2018, will comprise an installation of curved tables with reflective surfaces like puddles, reminiscent of L’Esprit du Nomade, a series first shown at the Cartier Foundation in Paris. A third, titled Fishes and Crows, will open in June 2018 at Friedman Benda in New York, and will consist of a series of works made between 1988 and 1992. And a fourth, which is planned for LA next year, stems from a past project that involved squashing Fiat 500s into artworks and may involve crushing another vehicle, but the details are still under cover. “I’m not destroying them,” was all the designer would give away, “I’m immortalizing them like pressed flowers.”

The Big Easy, 1988, in mirror-polished stainless steel. Courtesy of Ron Arad Associates.

Displayed in his basement gallery is a chair carved into a tree trunk, a version of which is to be the centerpiece of the Geneva exhibition, inscribed with the phrase: “Have nothing in your house that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful, or love.” These are the slightly altered words of William Morris, a figure closely associated with the arts and crafts movement in the UK in the second half of the nineteenth century, which advocated traditional craftsmanship over industrialization. It is an intriguing tribute given that Arad says he is not, and never wished to be, a craftsman, but hints that he shares Morris’s fascination for both utility and art.

Despite being a hefty chunk of wood, when you sit in the seat carved out of it you find, rather unexpectedly, that it glides back and forth smoothly, like a rocking chair. The piece exhibits a playfulness that permeates every corner of the studio—every shelf, ledge, and other available surface—from a crushed steel champagne bucket and several sets of spectacles to a 3-D -printed polyamide spiral, which manages to allure without suggesting an obvious purpose.

MT Rocker, 2005, in polished stainless steel. Courtesy of Ron Arad Associates.

The variety of steel chairs Arad has designed over the years, many of which are also kept here, is astonishing. Some invite you to sit on their curved forms, while others are made for you to lie down on at a variety of angles, depending on how they have been shaped. “At the beginning, my pieces were primitive and rough and badly made, so that became a post-rationalized way of discussing it: Why should everything be polished and finished?” he explains; “and then, when we got better and better at polishing and finishing, like you can see in the Big Easy, it’s like, ah, it’s finished! Like a big piece of jewelry.”

Useful, Beautiful, Love, 2016, in cedar and steel. Courtesy of Ron Arad Associates.

Arad’s use of metal has moved on since the Big Easy, a metal armchair designed in 1988 and made from three curved sheets of steel; but he is still as playful as ever, as shown by his new work, which is preoccupied with crushing. “It’s a dialogue between your will and what the material will agree to do for you,” he says, “and when you crush, the whole thing has a time element; you can see things happening in front of you.”

Flattening Fiat 500s with a hydraulic press has evolved into a more subtle use of steel, which is pushed into delicate folds in stunning two-story metal fireplaces. He has since moved on to the unapologetic crushing of three ninety-seven-foot-high heavy-duty metal columns, each four feet in diameter, for a new large-scale public commission that will be unveiled in downtown Toronto next spring. Safe Hands, as it is ironically titled, is designed to look as though it is about to topple over, thanks to the crushed lower sections and the fact that it will stand precariously close to the polished-mirror facade of a new building.

Pressed Flower, Red, 2013. Courtesy of Ron Arad Associates.

The studio also has several daring architecture projects underway that are no less artistically ambitious. A cancer hospital that will serve communities in both Israel and Palestine— the first such facility for residents of the West Bank—will be nestled into the sloping terrain and is designed so that patient waiting areas enjoy natural light. And a complex consisting of two towers, one of which will be the tallest in Tel Aviv, called ToHA, was inspired by the shape of an iceberg.

Although his work has defied set boundaries ever since he set up shop in the 1980s, there is something that makes Arad’s practice whole. “For each project, the objectives are different. The destination is different. The problems are different. The number of people involved is different,” he reflects, “but when I sketch for a building or when I sketch for a bench, it is the same pencil or the same tablet and the same history, the same likes and dislikes, the same curiosity that is at the base of everything.”