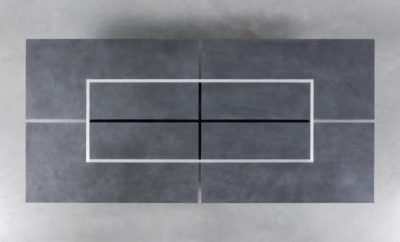

Land Rollers, 1992, as installed at Storm King, 1992–1994 | JERRY L. THOMPSON PHOTO, © URSULA VON RYDINGSVARD, COURTESY OF GALERIE LELONG

Land Rollers, 1992, as installed at Storm King, 1992–1994 | JERRY L. THOMPSON PHOTO, © URSULA VON RYDINGSVARD, COURTESY OF GALERIE LELONG

Design

A visit with Ursula von Rydingsvard

I’M TALKING TO THE SCULPTOR Ursula von Rydingsvard in her enormous, bright, and meticulously organized studio in Bushwick, Brooklyn. We walk through a portion of the second-story space where a lace template for lost-wax casting stretches across the floorboards. We pass a long wall where several hundred neatly hung objects demonstrate the range of her inspiration and experimentation: photographs, sketches, feathery and almost diaphanous works on handmade paper, tangles of hemp, beads, skeins of wool, netted sleeves, a pair of buoy-like sacs made out of cow intestines—like the ones that encircle the broad lip of her large bowl Ocean Floor.

Von Rydingsvard is a force of nature, a cyclone of energy and painstaking, hard work. Open, generous, plainspoken, graciously informal, she’s been making art since the late sixties, and her pieces and installations often have the blurred beauty of worn-away statuary or objects salvaged from the bottom of the sea. She’s best known for her layered, craggy, scarified constructions built from cut planks of milled cedar four-by-fours, sawed, stacked, and glued—cones, reverse cones, talismanic objects that convey dignity and gravity as well as familiarity.

Everything’s an object, you know, and the bowls are bowls. I even call them bowls, say, Bronze Bowl with Lace, but it’s an excuse, the bowl’s an excuse to reach out to other things. The bowl gets a surface that’s oriented toward something other than a bowl, that hopes to unfurl other things, other than to say “it’s a bowl” and then you say “good-bye”

Over a long career she’s experimented with many sculptural ideas and materials. One of her most stunning nature-based pieces is Land Rollers, made of seventeen giant and furrowed cedar cylinders rubbed with graphite, which was installed at the Storm King Art Center between 1992 and 1994. Much different, and hinting at her range, is katul katul, made from co-polyethelene and aluminum, a gangling, transparent bonnet-like structure suspended from the skylight of the atrium in the Queens Family Courthouse.

Her many huge bowls provide a context where she can explore endless sculptural implications without being too descriptive. As she says, they unfurl things: fertility, nourishment, emptiness, intimacy, fullness, openness. Like a Japanese potter, but using the medium of sawed and glued wooden blocks, von Rydingsvard explores the essence of the bowl and the pull of its gravity, while considering its curves and hollows, surface texture, coloration, weight, balance, the mysterious relationship between inside and out, its analogies to the human body or landscape—until it’s deconstructed. You can see this in documentary photographs of the splayed-out Can’t Eat Black, an installation at the Neuberger Museum of Art at Purchase College in 2002. Can’t Eat Black shows the anatomy of a von Rydingsvard bowl, each board cut on all sides, each ring of boards forming a profile that serves as a platform for the next tier, though in this case the bowl has been cut apart, sliced up, and bonded back. The raggedly feathered exterior surfaces encircle an interior that looks like a buckling cobbled street—whole sections threatening to fracture and fly out in hundreds of directions.

Even though her work can be massive (Ona, made in 2013 and cast in bronze, weighs nearly twelve thousand pounds), both sensuality and fragility hover over von Rydingsvard’s objects. One of her more recent works, the heroically scaled Bronze Bowl with Lace, stands nearly twenty feet tall, crowned with intricate folds of metallic fretwork. On one hand, the sculptural surface is cragged like the stone cliffs of a sea cave or the bark of an ancient tree, but from a distance the body looks like a bouquet, and the patterned band of bronze lace at the top mimics the intricacies of billowing and delicate needlework with its pattern of positive and negative space filtering light.

When I ask von Rydingsvard about the play of hard and soft, the magic of making her solid materials—cedar, bronze, and more recently copper—allude to fabric, she nods and says slowly, “I’ve thought about cloth for decades.” She shows me a gift she relishes: bags and bags of collected lace brought to her studio by a friend. “Do you see how rich I am?” she asks teasingly as we examine the multitude of patterns made with bobbin and needle.

On the weekends and when she travels, von Rydingsvard likes to roam the flea markets. In China she found finely sewn silks, “very old things that are so intricate you can’t believe anyone would have the endurance to see it through,” and in Japan there were tie-dyed fabrics and kimonos: “They make the smallest little knots that they tie with a string, the smallest little knots by the thousand, by the millions, and dip them into their dyes. It’s just something that feels almost holy to me . . . . I went to Kyoto and there was this mountain of kimonos . . . and, oh, what it takes to make a kimono, the care and even learning to fold and unfold them. I would do it over and over again.”

Work—time-consuming,repetitive work using her hands and her body—has been a mainstay throughout von Rydingsvard’s life. “It’s good for me mentally, it’s good for me physically,” she says. In the downstairs rooms of her studio, where many sculptural pieces are in various stages of completion, you get a sense of the artist’s grueling regimen. The space resembles a lumberyard with scaffolding, forklifts, ladders, hand trucks, shelves supporting tons of wooden beams, rope, pipe clamps, drill bits, discarded gloves; and yet she says everything begins with pencil marks on the floor, the foundational shape for a new base. With a small group of assistants (two for the cutting process, one for gluing), she works silently, penciling a shorthand of instructions on all sides of every cedar beam, and then building layer by layer, cutting each piece of wood with a circular saw and gouging with chisel and mallet, screwing planks into place, assembling thousands of coded pieces, and then disassembling the entire construction, gluing, reassembling, brushing graphite into the crevices and onto surfaces, polishing, and vacuuming.

Reflecting on craftsmanship, von Rydingsvard says, “I think, to be too aware, to see too clearly the craftsmanship of a piece is often a turnoff for me . . . just being well-made, that’s in the realm of not being very interesting.” You recognize this aesthetic in her sculpture, never over-determined even when it’s the product of months or years of physical labor. She likes to talk about her materials seeming to misbehave. Her work often looks like ancient, half-forgotten remnants of statuary that have survived by chance. This is especially apparent in her artifactual forms—spoons, shovels, collars, plates, combs—somber and dreamlike, simple objects freighted with personal meaning: “There’s something in me that I would have been had that war not happened,” she says, explaining how her objects bridge two worlds, broken apart by World War II.

Von Rydingsvard was born in Deensen, Germany, in 1942, the fifth of seven children in a family that had been peasant farmers for generations. Her mother’s family was Polish, from the region near Zakopane. Her father was a Polish-speaking Ukrainian. The family was deported to Germany during the war and her father worked as an agricultural forced laborer under brutal conditions. Afterward, not wanting to return to Communist Poland, they were transferred through eight displaced-persons camps, living in unheated barracks, the children dressed in pants made from Army blankets and playing with bricks and sticks. Finally, in 1950 they were resettled in Plainville, Connecticut. To support the large family, her father took on two factory jobs, a day and a night shift, and worked as a gardener on weekends. Her mother went to work in a restaurant and the children had to take care of one another, trying their best to make sense of the indignities and brutality of immigrant life in a small American factory town.

History uprooted her family from Polish farmland and folk culture, but it also positioned her—through untiring work, discipline, and imagination—to get a B.A. and an M.A. from the University of Miami, to become an artist with an M.F.A. from Columbia University, and to break into the international art scene.

With their rough-hewn quality, scarred and pocked, von Rydingsvard’s domestic objects and tools are reminders of both the disruption of the war and an idealization of what existed in a vanished place: “I think it’s something unconscious because I never grew up in Poland, I never grew up in the Ukraine . . . . You know, I don’t really want to make another bowl but it keeps surfacing—and you mentioned the spoons and the shovels, . . . so there’s this bowl that needs to be filled. I never fill it, right, it never gets filled and I can’t even say it’s more filled than it was thirty-five years ago, before I even started making art, but it fuels a will that doesn’t want to stop.”

Paul’s Shovel is the essence of a shovel or its approximation, not one meant for digging; almost seven feet tall and made from milled cedar, it’s intended to hang in the air, suspended on a wall as an abstraction. This shovel looks as though it’s been forgotten in the damp corner of an old shed until it’s become worn away into an indeterminate form. Pared down in this way, it stands as an amalgam of a farmer’s tool and the not-quite-defined body of a man, an emblem for work and excavation, and a reference to her husband, Paul Greengard (possibly to his life of hard work; he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2000), and perhaps a wistful allusion to the life her father might have led had he not been displaced by the war.

Like Paul’s Shovel, the Weeping Plates are blown up larger than any plate might be and then flattened and stretched so they become irregular circles shaped like the loops in a de Kooning painting, biomorphic forms with their edges roughly rolled over. The bottoms are fringed; as von Rydingsvard has said, “they feel almost like an unraveling of something.” Because they’re magnified they’ve become symbolic, bringing to mind hunger, fullness, sanctification of food, or bread itself. It’s not unlikely that they carry trace memories of the large serving plates families ate from in the displaced-persons camps, and since they’re shield-like they fuse the concept of a mother’s protection with her role as food provider. “Everything fell apart when our mother wasn’t home. It was our mother we were in love with,” von Rydingsvard says.

Though von Rydingsvard thinks of her work sculpturally rather than architecturally, the rough plank construction of the wooden barracks and the bricks and sticks she played with as a girl have been seminal to her artistic imagination. She talks about how she used to fantasize about the architecture and landscape of Poland. In 1985, when she was on the faculty at Yale, she received a Griswold Grant that allowed her to travel there, and in the early 1990s she went back again. “I went to Zakopane, not far from where my mother was born,” she says, adding: “In Zakopane all the houses are made out of wood and they also have a kind of lace over their doors, and wood for their roofs, and under the bottoms of their roofs, and so on. Wood is extremely important to them.” She tells me how an older woman took her to hear a singing group practicing in the mountains near Zakopane, “singing from one mountain top to another, and it would echo . . . they were answering one another, back and forth.” She began to weep while they were singing, she recalls. “I couldn’t stop my tears . . . something like that has only happened, maybe you can count on one hand.”

In 2006 von Rydingsvard completed Damski Czepek (Old Woman’s Bonnet), a dwelling-like structure shaped like a bonnet with curving ribbons but large enough for viewers to walk right under its frilled brim, or “porch” as the artist calls it. The bonnet was made first in cedar and then cut into sections so it could be cast in polyurethane resin. It’s luminous and welcoming, yet its shell holds the impression of the blocks from which it was molded. It is thus both a translucent space and an offshoot of the wooden cottages of Zakopane. Like her bowls, it unfurls many things: an affectionate gesture to childhood, to childhood games like hide-and-go-seek, and to Zakopane’s ornamental architecture. With its brimmed opening, it carves out an intimate space and invites you once again to explore the relationship between inside and out.