Design

A Landmark Show Examines Ceramics by Ettore Sottsass

AN EXHIBITION AT FRIEDMAN BENDA IN NEW YORK BRINGS TOGETHER THE MASTER DESIGNER’S IMPORTANT CERAMICS

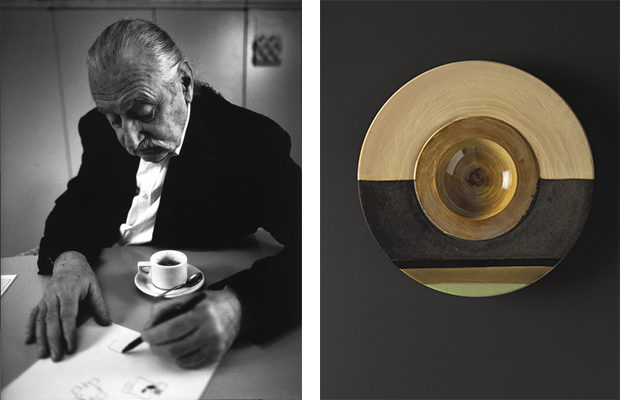

Designer Ettore Sottsass.

“If there is a reason for the existence of design, it is that it manages to give—or give anew—instruments and things this sacred charge for which […] men enter the sphere of ritual, meaning life.” — Ettore Sottsass

IN PHOTOGRAPHS, ETTORE SOTTSASS (1917–2007) is mustachioed, heavy-lidded, and dark, his expressions running from bored to thoroughly unimpressed. In one he sits on a stool, a cigarette between his fingers, long-haired, stone-faced. In another, among a pile-up of grinning designers in a boxing ring–shaped bed, he is against the ropes, head in hand, aloof. If ever a face masked a deep and long- standing interest in human expression, it was this one.

Over some six decades beginning in the late 1940s, Sottsass worked to restore a sense of humanity to a field that had all but sacrificed it to function. Arguably he is best known today for his central role in the Memphis group, a collective of designers that used a visual vocabulary of ungainly forms, off colors, and deliberately tasteless, clashing prints like an eye roll or ironic turn of phrase. But Sottsass’s interests went far beyond visual wit and deadpan delivery. He mined human history and experience for touchstones as diverse as contemporary art, ancient architecture, traditional craft, and Eastern spiritualism to cultivate a design language that was often as sober as it was spirited, as profound as it was playful. This is most apparent in his ceramics, a medium he discovered in 1955.

Plate from the Offerta a Shiva (Offerings to Shiva) series, handmade by the designer after recovering from a severe illness. Of the one hundred created, no two are alike.

By the late 1950s Sottsass was already being recognized as a formidable talent and a design polymath. He became the art director of Poltronova, a newly established Italian furniture manufacturer known for producing work by young designers associated with the Radical Design movement. The period also marked the beginning of a fruitful collaboration with Olivetti that saw Sottsass design the Elea 9003 mainframe computer, for which he would be awarded the Compasso d’Oro, Italy’s highest achievement in design. In 1957 Sottsass realized his first series of ceramics for Bitossi, an Italian ceramics manufacturer, for distribution by the New York-based importer Raymor. Invited by Raymor and Bitossi to design the line in 1955, Sottsass was immediately attracted to the medium.

An original Rocchetto (Reel) vase, 1962, in terracotta with a slick of aqua glaze.

Marc Benda, whose gallery Friedman Benda represents Sottsass and will be showing the late designer’s early work in an exhibition on view to October 17, notes that he was drawn to the immediacy and versatility of the material, as well as its history. “Ceramic, clay, earthenware, stoneware. They’re materials that date back thousands of years in Italy,” Benda says. “The Etruscans, the Greeks, and in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance with majolica.” Sottsass spent two years experimenting with the medium before his designs were produced, and the resulting work, the Ceramiche di Lava (Lava Ceramics), established qualities that would guide his ceramics for decades.

The Lava series shows the designer manipulating the basic qualities of the clay, pairing fields of smooth glaze against sections with a coarse and porous finish resembling lava rock, and offsetting neutral tones with acid colored glaze, daubed on, edges uneven. The pieces are pleasingly curved and substantial, with a visual heft that signals durability and utilitarianism. Their forms also have a deliberately primordial character. In a 1970 issue of Domus Sottsass wrote of “ancient bowls with very primeval colors or ancient goblets, goblets like the ones maybe used in Mycenae or in Galilee or in Ur or any other place, to drink water gushing from a spring. It seemed to me then that it was possible to rediscover archetypal forms (and I’m not talking about essential forms, because the essence makes us think of an ideal state or a more or less Platonic metaphysical absolute, and not of archetypal forms), in other words, forms discovered by humanity at the dawn of time and that are deeply embedded in its history.”

Sottsass’s second line for Italian ceramics manufacturer Bitossi, Bianco/Nero (White/ Black), 1959, was based on archetypal forms, “forms discovered by humanity at the dawn of time and that are deeply embedded in its history.”

Sottsass’s interest in archetypal forms would persist through several more series, including 1959’s Bianco/Nero (White/ Black)—pieces composed of striped and gridded cylinders and bowls assembled in various combinations that resemble a child’s interpretations of bottles and cups; and Rocchetti e Isolatori (Reels and Insulators) in 1962, glossy ceramics inspired by spools and electrical insulators. The title of a 1967 exhibition of large-scale ceramic objects, Menhir, Ziggurat, Stupas, Hydrants & Gas Pumps, suggests the designer culling inspiration from a range of sources—from ancient monoliths to contemporary cityscapes—and transmuting it into large ceramic totem poles, some more than two meters tall, composed of separate discs—like giant Life Savers—in brilliant colors and graphic patterns stacked one atop an- other on a metal pole. For two series in the late 1960s—Tantra, 1968, and Yantra, 1969—Sottsass looked to Hindu spiritualism, translating tantric diagrams into ceramic vessels. Rendered in three dimensions, the concentric circles and triangles echo the steps of a ziggurat, or the radiating, reverberating forms of art deco.

A 1962 study for a Tenebre vase.

While Sottsass chiefly designed for serial production, he hand-made two sets of ceramic objects that transcended formal references to express a more profound and personal spiritual outlook. He completed the first, Ceramiche delle Tenebre (Darkness Ceramics), in 1963 while convalescing from a severe illness contracted during a trip to India. A series of large cylinders glazed in black, muted blues, and burnished bronzes, platinums, and golds, with a motif of circles—full moon and eclipsed—the pieces are both a reflection of the bleakness of this period and a rumination on our connection to the universe. Sottsass created the following series, Offerta a Shiva (Offerings to Shiva), dedicated to the Hindu deity Shiva, who embodied both destruction and regeneration, to mark his return to good health. In flesh and earth tones, ochers, pinks, and oranges, with incised circles representing the cosmos, the mood of the plates is more reverent gratitude than jubilant celebration. “They’re almost a meditative reflection on mandalas, on Hindu iconography,” Benda says, “but at the same time, there’s nothing in [the series] that seems repetitive. If you saw all of them you wouldn’t once feel that you’ve seen that motif before.”

“With my work […] in the end I try to be the least modern possible, and as timeless and spaceless as possible to get people to acknowledge the presence of objects,” Sottsass wrote in 1964, declaring his design manifesto but also his world view. “Not as consumer goods, but as instruments of a possible ritual—if we can make a ritual out of life.”