COURTESY OF GALERIE PATRICK SEGUIN.

COURTESY OF GALERIE PATRICK SEGUIN.

Design

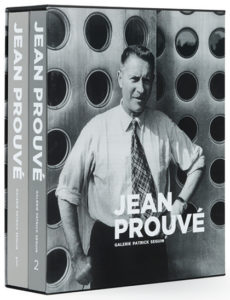

A comprehensive monograph shines a light on the furniture of Jean Prouvé

JEAN PROUVÉ CALLED HIMSELF A “WORKER,” not an architect or designer. This may reflect the Marxist language of the first half of the twentieth century, but it also shows how his love of metalwork, industrial processes, and standardization drove his identity as a designer. Equal parts pragmatist and poet, Prouvé made work that was informed by his fusion of form and function, his strength as a colorist, and his belief in the power of design to improve everyday life.

Jean Prouvé published by Galerie Patrick Seguin • distributed by Interart & D.A.P, $225

A new double-volume, 750-page monograph on his furniture, published by Galerie Patrick Seguin, reveals that Prouvé emerged almost fully formed as a designer. After creating a pair of folding chairs— signaling an early interest in portability and flexibility—and the wooden Cité chair, Prouvé arrived at his Chair No. 4 in 1934, a metal-framed chair with a wooden back and seat with tapered rear legs. Chair No. 4 would become the foundation for a large series now grouped together as the Standard chairs. Arguably his best known and now most widely produced works, Standard chairs (reissued by Vitra) feel as familiar as school cafeteria seating, but are elevated by Prouvé’s stark, yet elegant forms. The tapered rear legs are designed to carry more weight, because Prouvé liked to lean back in his chairs, balancing only on the rear legs—precisely the kind of detail he would translate into his furniture.

COURTESY OF GALERIE PATRICK SEGUIN.

Featuring a brief essay by Jean Nouvel and a lengthy interview with Renzo Piano, Jean Prouvé serves as a catalogue raisonné of the designer’s furniture, lighting and storage pieces. Generously illustrated with photographs, drawings, and other archival material, the book is satisfying and informative, especially for American readers who may be less familiar with his oeuvre. Nou- vel calls him the “Anti-esthete.” Perhaps. But then, why do so many find his work so utterly beautiful?

For a time, Prouvé owned his own factory, and therefore his own means and profits of production, but he lacked the marketing prowess of such American designers as Charles and Ray Eames or George Nelson. If these designers were emblematic of American postwar optimism, Prouvé’s vision was more akin to neorealist filmmaking: blunt, direct, and— above all—modern.

COURTESY OF GALERIE PATRICK SEGUIN.

While Prouvé achieved success and some renown—primarily in Europe—for his own work, he also helped usher in a sea change in design. Like Eero Saarinen spotting the genius of Jørn Utzon’s design for the Sydney Opera House, Prouvé chaired the jury for the design competition for the Centre Georges Pompidou, and was instrumental in selecting the proposal by Richard Rogers, Renzo Piano, and Gianfranco Franchini. The building launched the careers of Rogers and Piano and changed architecture forever. Prouvé, the son of a leading art nouveau artist, was a living bridge from the design thinking of the nineteenth century straight to the twenty-first.

One hopes the gallery will also bring out a volume on Prouvé’s remarkable prefabricated architecture. These portable buildings hold lessons for the challenges of today and tomorrow.