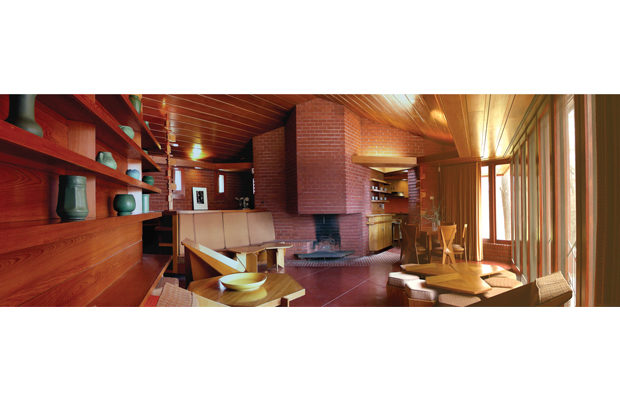

The open living and dining area of the Kraus house with the central hearth as well as the furniture and built-ins designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Photo by Kristen Peterson.

The open living and dining area of the Kraus house with the central hearth as well as the furniture and built-ins designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. Photo by Kristen Peterson.

Feature

Open House

The restored Kraus house in Saint Louis is a Frank Lloyd Wright Usonian Gem

Another view of the open living and dining areas, with the terrace doors to the left. The art pottery on the shelves was collected after the house was made into a museum. Sheree K. Nielsen photo.

For decades, Ruth and Russell Kraus lived quietly in their small modern house in Kirkwood, a Saint Louis suburb. Few people other than their friends and acquaintances even knew that there was a Frank Lloyd Wright treasure tucked into the secluded wooded site. But the house built between 1951 and 1955 for the Krauses, she a lawyer and he an artist, is not only exemplary of Wright’s work and way of thinking but also stands as testimony to what can happen when a small but determined group of people bands together to preserve historic architecture.

After Ruth Kraus died in 1992, Russell realized he needed to sell the house and agreed to a plan to preserve it as a Frank Lloyd Wright museum. A nonprofit organization was formed and, after an eight-year effort, $1.7 million was raised to purchase the house, its original furniture, memorabilia, and ten and a half acres as of January 18, 2001.

Today Ruth and Russell Kraus’s house is owned by Saint Louis County and operated as a house museum by the nonprofit Frank Lloyd Wright House in Ebsworth Park, the name also formally bestowed on the house. The property it sits on is a county park named for Alec W. and Bernice W. Ebsworth, the parents of philanthropist Barney Ebsworth.

Wright began designing his Usonian houses in the 1930s for middle income clients with the understanding that these modest and economical dwellings would be integrated into the surrounding landscape. This is particularly true with the Kraus house, which is sited in a lovely grove of persimmon trees and nestled into a hillside surrounded by woods and grassy fields.

To reduce costs in his Usonian houses, Wright advocated a simplified approach to construction and a paring down of elements. He developed a “unit system” method of design based on geometric shapes—squares, rectangles, equilateral triangles, hexagons, and parallelograms. For the Kraus house, he used intersecting parallelograms with 60 and 120 degree angles, which created geometric intricacies and dynamic spaces.

The Kraus house has all the elements that Wright considered essential. True to Wright’s Usonian concept, the floor plan is open, including a living room, with a large central hearth, and shared dining area looking out onto vistas of the persimmon grove and woods beyond. The living and dining space opens onto an adjacent, efficient kitchen, and what Wright called the “work space.” The bedrooms are small, typical for Usonians, but the Kraus house is one of the few Wright houses in which the shapes of the beds conform to the geometry of the house. The entire house features built-in furniture, storage, bookshelves, and indirect lighting. It is efficiently warmed by radiant heat, with hot water flowing through pipes embedded in the concrete slab. The Krauses made no structural changes and retained all the original furnishings, making the house an exceptional historical document as well as rare in a world where change is constant.

Like other Usonians, Wright designed the house without a basement, attic, interior trim, radiators, overhead lighting, gutters, downspouts, or a garage (a carport was sufficient). Materials are the same inside and out: brick, concrete, tidewater red cypress, and glass. The interior walls are of wood board-and-batten construction, requiring no paint or plaster.

This expansive view of the house from the southwest gives a sense of the dynamic angles of Wright’s design. The motor court is on the right, with the tool house at the end. Nielsen photo.

The architectural attributes and historical importance of the Kraus house were evident, but the years had not been kind to it. Financial constraints in his later years had left Russell Kraus unable to adequately maintain the house—water had proved particularly destructive. After research, Chicago architect John Eifler, known for his expertise and experience in the restoration of Wright Usonian houses, was selected to direct the project. Jeff Markway was chosen as the contractor.

Throughout the restoration, museum quality standards and museum quality craftsmen were used. Original finishes and materials were preserved whenever possible. Stains were painstakingly removed from tables, countertops, and other furniture rather than removing original finishes.

Neglected exterior cypress was cleaned, restored, and treated with Sikkens, a protective wood coating. The terrace doors had suffered too much water damage to be saved, so new cypress doors were constructed; the original stained glass designed and executed by Russell Kraus (who was not only a painter but a designer of mosaics and stained glass) was reinstalled in the doors. Adding gutters to the roof above the doors would prevent further water damage, but this was not an option because one of Wright’s core principles was that houses should be low and parallel to the ground and that gutters and downspouts called attention to the vertical rather than the horizontal. The contractor suggested slightly slanting the door sills to shed water, and to repeat a layer of Sikkens whenever the wood begins to weather.

Drainage issues affected the brick even more dramatically than the wood. Wherever the brick was exposed to the elements, it had spalled. Forty percent of the brick had to be replaced, including walls of the motor court, main terrace, and master bedroom lanai. Eifler found new brick in Sioux City, Iowa, that was a perfect match to the original Alton Brick, which was no longer available.

The doors to the main terrace incorporate stained glass designed by Russell Kraus. Nielsen photo.

Throughout the restoration, the walls were made to look as Wright intended, but were fortified with protective measures to help prevent future disintegration. For example, when rebuilding a brick living room wall that had buckled from the weight of the vaulted ceiling, steel rebar was incorporated into the brick to make the wall stronger and better able to absorb the weight of the ceiling. Old brick was salvaged and reused on the new wall, so all the brick inside the house remains original.

Restoring the concrete that Wright prescribed for inside and out has been the most challenging task. Wright liked to use red concrete—which he called Cherokee red, as it reminded him of the earth, of clay—and almost all Usonians have aging red concrete damaged by staining and weathering. The repair of concrete is complicated, however, because it absorbs products deeply; if the wrong product is used, the concrete cannot be returned to its original state. John Eifler suggested Kemiko English red wax for the interior concrete, which blends beautifully into Wright’s original floor. A search continues for the right products and methods to restore the coloration of the exterior concrete, watching how other Usonian owners handle this ubiquitous problem.

Saint Louis Art Museum textile curator Zoe Perkins directed restoration of the original Schumacher fabrics used for drapes, bedspreads, and chair, bench, and floor cushions. Replacing cracked drapery linings, shortening draperies, spotting, and vacuuming the fabric were all done by hand to protect the fragile materials.

Electrical problems included replacing aluminum light fixtures built into the brick terrace walls. The fixtures, intended for interior use, were dangling, exposing the light bulbs. They were rewired and replaced with exterior-grade aluminum fixtures, but water seepage continues to be a problem. Still, the nighttime glow of these lights is magical.

To improve the electrical system, wires were buried underground and fed to circuit breakers, which replaced old fuse boxes. Recently, wiring in the tool house failed and electricians had to dismantle part of the ceiling to gain access to brittle wiring, which led to a new challenge—how to replace the sixty-year old particle board ceiling that crumbled when panels were removed. (A similar particle board was eventually found by the contractor and stained to match the original.)

One of the three Taliesin lamps Wright designed for the Kraus house, all different from one another. David Ulmer photo.

It is nerve-wracking to care for a Wright house. There are constant concerns about what will need to be fixed next and who is trained, sensitive to historic restoration and Wright’s original intention, and available to make the proper repair. It can make one crazy, but it is worth the challenge. Now, visitors from all over the world are able to experience a Usonian house just as Wright intended it.

The house is open year-round for guided tours, Wednesday through Sunday, by advance reservation only. For further information, call (314) 822-8359 or visit ebsworthpark.org.

Joanne Kohn led the campaign to raise the money to save the Kraus house and open it to the public, oversaw its restoration, and has chaired the nonprofit board that operates it since 1997. Laura Meyer has been administrative director of the house since 2008.

Several other Usonian houses are open to the public, including the newly restored Kenneth and Phyllis Laurent House in Rockford, Illinois, which opens on June 6. Considered by Wright to be one of the thirty-five best works of his career, it is the only building he ever designed for a person with a disability—a wheel-chair-bound World War II veteran and his wife. Visit franklloydwright.org for a list of the Usonian and other Wright houses that are open to the public.