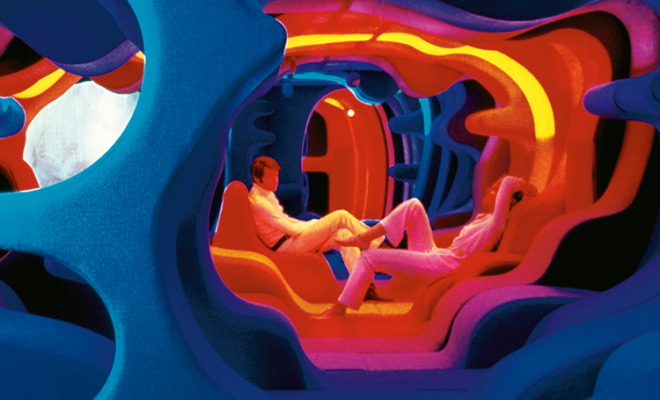

Inside Panton’s exhibition at the Cologne Furniture Fair in 1970. Named Visiona 2, the environment-like installation immersed visitors in a sea of colors and undulating forms. ALL IMAGES COURTESY OF PHAIDON, © PANTON DESIGN, BASEL

Inside Panton’s exhibition at the Cologne Furniture Fair in 1970. Named Visiona 2, the environment-like installation immersed visitors in a sea of colors and undulating forms. ALL IMAGES COURTESY OF PHAIDON, © PANTON DESIGN, BASEL

Architecture

A New Book on Verner Panton: Pop and Practicality

“A LESS SUCCESSFUL EXPERIMENT is preferable to a beautiful platitude,” said Verner Panton, one of Denmark’s most important and most distinctive design personalities. In his time, he was considered an enfant terrible, but he was in truth a trailblazer who combined pragmatic design approaches with a direct use of the possibilities made available by the new technologies, materials, and production systems that emerged in the postwar era.

His designs are renowned for their attempt to engender innovative design experiences, especially through the use of color, but are also characterized by an almost scientific approach to the exploration of systems as a basis for the development of chairs, lamps, textiles, and celebrated interior “environments.”

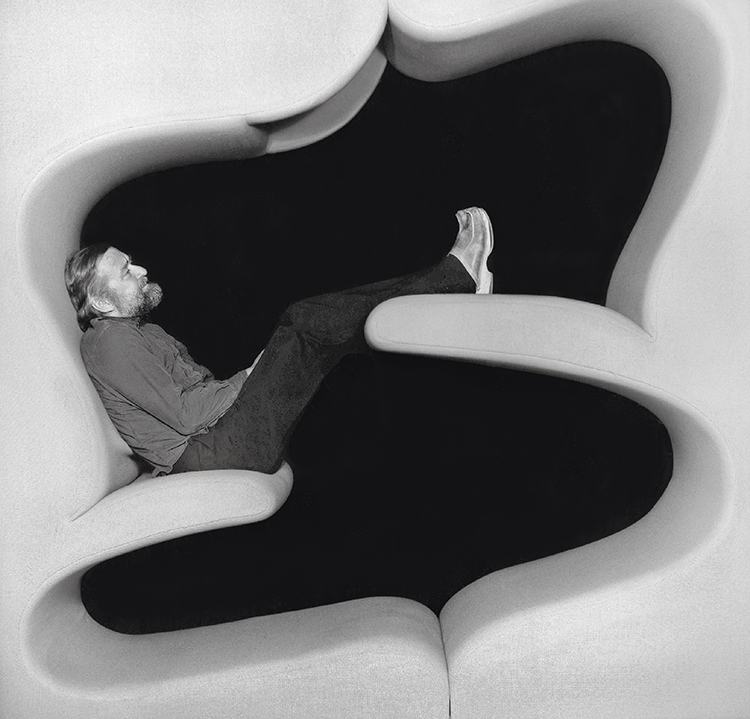

Panton pictured inside his Living Tower, a sculptural furniture piece consisting of two elements with four seats on different levels, 1968.

Panton was “Danish” in the sense that he shared the practical and concrete design approach that characterizes the Danish furniture tradition among his colleagues. But he appears much less “Danish” if we consider his experiments with new materials and idioms, and the role that he assumed on the Danish design scene. In Denmark, Panton’s furniture-design colleagues worked with wood and natural materials, while he worked with plastic, Plexiglas, steel, foam rubber, and other synthetic materials. And while his colleagues were cultivating modernized craft-related traditions, Panton was aiming to create fully industrially manufactured products intended for the mass market.

The interior of Restaurant Varna in Århus, Denmark, as designed in 1971 by Verner Panton and featuring his Pantonova chairs, 1971, and chrome Spiral lamps, 1970.

His most radical designs were his environments. They were completely in tune with the international zeitgeist of the 1960s and 1970s, when, analogously, architectural projects such as Archigram in England and Archizoom Associati in Italy were developing visions for the innovative use of postwar technologies and systems in environments for modern life. Panton contributed to the international movement and supplied some of its most radical expressions, such as Visiona 2 from 1970, which even today calls to mind a futuristic spaceship.

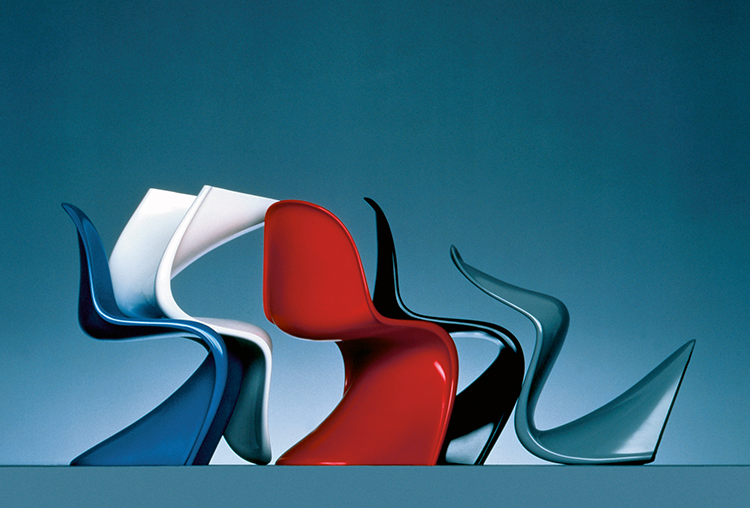

Panton chairs, 1956–1967, from the archives of the Vitra Design Museum in Germany. From the start, the chair was produced in a variety of colors.

However, in contrast to the experiments conducted by Archigram and Archizoom Associati, Panton’s formats were closer to the users, and it was specifically the practical and often lowcost results that were put into production. Many people know the Flowerpot lamp because they own, or have owned, one. But Panton also enjoyed exaggerating and pushing the boundaries recognized by ordinary people.

The swimming pool in the basement of the Spiegel publishing house, 1969. Unfortunately, the pool was destroyed by fire, but it is richly documented in photographs.

In fact, Panton was abreast of the social conventions associated with “ordinary people.” He entered the postwar era as part of a great movement that believed in widespread social progress, either by means of sophisticated design solutions or through the reforms that ultimately gave rise to the social welfare models that currently inspire people around the world.

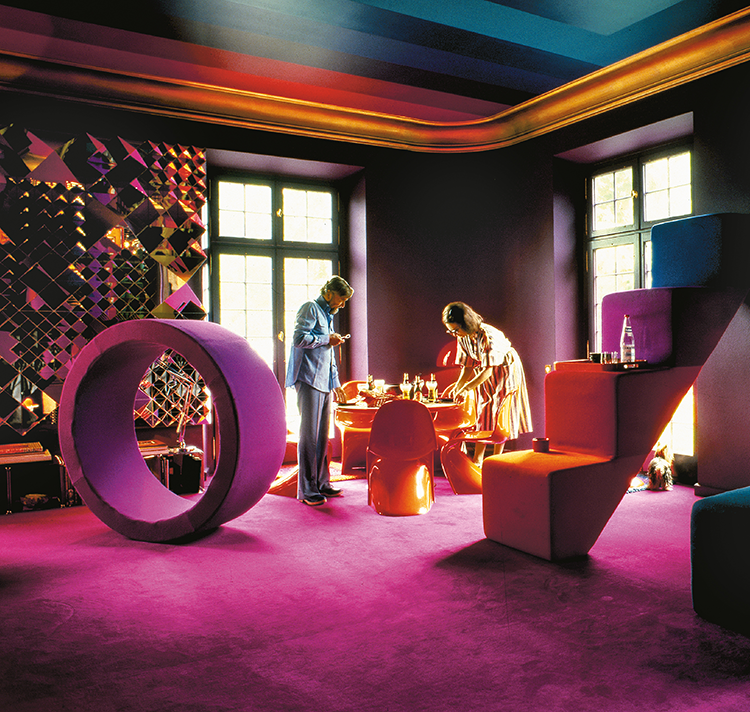

Marianne and Verner Panton at home in Binningen, pictured with Panton chairs, 1956–1967, Sitting Wheel, 1974, and Sitting Stairs, 1973.

Somewhere in the midst of the cultural, artistic, and aesthetic developments that characterized the first decades after World War II, we find Verner Panton and his universe of design. It is a universe that has now been absorbed by the processes of globalization, which in this context simply means that a growing number of people seek almost the same thing that appealed to Panton: an essentially exciting and challenging life, but also a socially mobile life; a comfortable life, as embodied by Panton’s Bachelor chair—simple, light, elegant, and eminently portable.

Panton seemed in step with Poul Henningsen’s dictum: “The future comes by itself; progress does not.”

This article is adapted from the author’s new book, Verner Panton (Phaidon, $95).

This article is adapted from the author’s new book, Verner Panton (Phaidon, $95).