MICHAEL R. BARNES PHOTO/SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION

MICHAEL R. BARNES PHOTO/SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION

Architecture

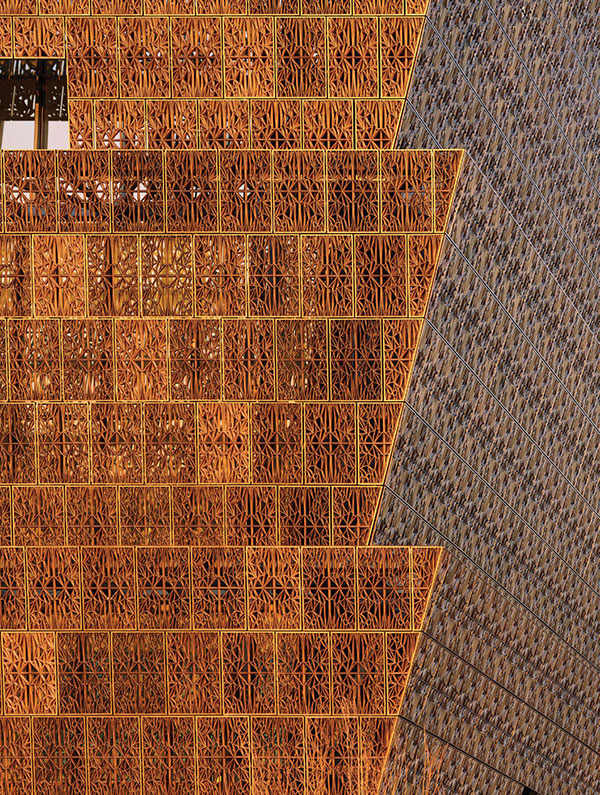

David Adjaye’s Elegant Homage

THE NEW NATIONAL MUSEUM of African American History and Culture designed by architect David Adjaye is set to open on September 24 on the mall in the nation’s capital. For architects and designers, it is, perhaps, the most anticipated design to land on the mall in many years after several recent designs took rather well-worn approaches.

The Adjaye design is unlike anything the city has seen before: a “dark presence in a city of white marble,” as the museum’s Deputy Director Kinshasha Holman Conwill calls it. But dark here is a color, not a mood. The design is anything but brooding.

Like an inverted ziggurat, the bronze colored filigree façade takes its cue from the crown-like capital of a West African Yoruban column, which the architect refers to as a corona. The cladding also borrows from architectural ironwork made by African-American artisans in the South.

ALAN KARCHMER PHOTO

The cladding “is variable in density, to control the amount of sunlight reaching the inner wall,” Adjaye wrote in an email. “During the daytime, the outer skin can be opaque at oblique angles, while allowing glimpses through to the interior at certain moments.”

The filigree façade covers what is essentially a glass atrium cube atop a stone-clad base. Openings in the corona frame vistas of the National Mall, symbolizing views of the nation’s capital through an African American “lens.”

“Those 3,600 panels are viewsheds that let you look out onto the mall, so within this African American space you look out at this cartography of the American capital,” Conwill says.

Initially, the façade was to be bronze, but the weight of cantilevering the metal screens off the core proved too heavy—to say nothing of too costly. Instead the panels were made of aluminum with a five-step bronze-colored finish. “Value engineering is just a part of the process,” Adjaye says. “In this case, the choices we made relating to the material for the façade were more about refining an idea and working out how to make it viable—economically, environmentally, and structurally.”

Much of the exhibition space rests underground, influenced in part by the National September 11 Memorial and Museum in New York designed by African-American architect J. Max Bond Jr., whose firm Davis Brody Bond collaborated with Adjaye Associates. Both museums deal with weighty issues at a subterranean level before guiding visitors up to a redeeming light-washed atrium.

The corona form “is a ziggurat that moves upward to the sky, rather than downward into the ground. And it hovers above the ground,” Adjaye writes. “When you see this building, the opaque parts look like they are being levitated above a light space, so you get the sense of an upward mobility in the building. And when you look at the way the circulation works, everything lifts you up into the light.”

Outside the museum, landscape architect Kathryn Gustafson of GGN applies a very light touch with trees native to the Southeast, including a reading grove of “brush arbor,” which would’ve been familiar to plantation slaves as a place to gather for prayer, get away from the main property, or plot an escape.

MICHAEL R. BARNES PHOTO/SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION

Conwill says that the initial design process began with a poem—Langston Hughes’s “I too,” in which he writes, “I, too, sing America, I am the darker brother.” “It really started in those regions of poetic imagination, even before there was a design team,” Conwill says. “Poetry has led the way to concepts of history.”

Adjaye says he drew inspiration from the music of his brother, composer Peter Adjaye, as well as from his playlist. He also cited Jun’ichirō Tanizaki’s essay on Japanese aesthetics, In Praise of Shadows, as the first among many books he read while working on the project.

The selection of Adjaye, who was born in Africa and is based in London, conjures questions as to why an African American wasn’t chosen, though the African American– led Devrouax & Purnell, who submitted a proposal with Pei Cobb Freed & Partners, was a finalist. “As the design process started it became fitting that, as the story starts in Africa, having an African architect made a lot of sense,” Conwill says. “In the end it didn’t seem strange that those who work in the diaspora could work here, and ultimately it became an African and African Americans designing this museum.”

As a Smithsonian Institution, the museum wasn’t required to hire a certain percentage of minorities, but Conwill says the museum took pains to bring diversity to the construction team and set goals of hiring 15 to 20 percent minority- and women-owned businesses. She added that that exhibition designer Ralph Appelbaum brought in a primarily African American team. And Derek Ross, who is African American, managed construction.

Yet, the completed museum and the resulting media attention will no doubt place Adjaye front and center as a media spokesperson for the African American experience.

“For me, the story is one that’s extremely uplifting, as a kind of world story,” he says. “It’s not a story of a people that was taken down, but actually a people that overcame and transformed an entire superpower into what it is today.”