Design

Spring 2011

Reviews of new books on movie sets, fashionable vintage fabrics, a design icon’s foray in South America, and insiders’ advice on collecting modern design

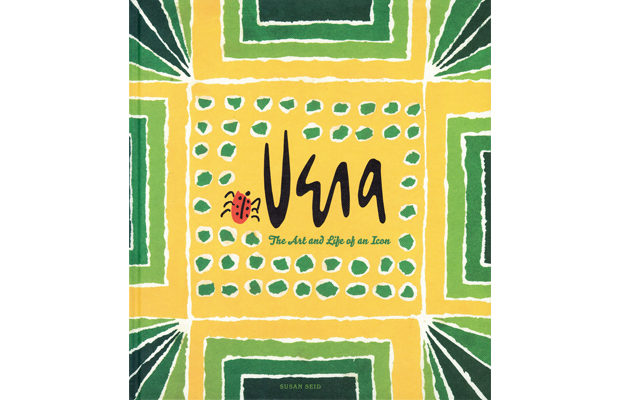

TO FASHION-MINDED women of a certain age, the name “Vera” conjures memories of a chic and snazzy era in the world of couture and houseware designs. In her heyday in the 1960s, textile designer and pattern maker Vera Neumann’s signature diaphanous scarves were a part of every elegant daywear ensemble, while thousands of homes were adorned with her products, ranging from placemats to curtains. Trained in art at New York’s Cooper Union, Neumann excelled at floral designs, patterns based on cityscapes, and abstract compositions that included both geometric and organic influences. Vera: The Art and Life of an Icon, with an introduction by Susan Seid—now head of the Vera Company—and main text by the lucid New York design journalist Jen Renzi, tells the engaging story of Neumann’s “up-by-the-bootstraps” career. Aided by her husband, George Neumann, a businessman with knowledge of both marketing and textiles, Vera built a firm that began with a dining tabletop-sized silk screen into a company that employed hundreds and produced a prodigious number of designs. She was friends with Alexander Calder, whose sculptures inspired several of Vera’s designs. This book is a delightful paean to a designer, and a design era, full of verve, color, and panache.

VERA: THE ART AND LIFE OF AN ICON By SUSAN SEID and JEN RENZI

Abrams, 208 pages, $35

AN EXHIBITION catalogue from New York City’s Gallery BAC, Jean-Michel Frank in Argentina—available only via Amazon.com—deserves a place in any modern design devotee’s library, both for the incisive essay by design historian James Buresh and for the book’s period photographs. As Buresh details, Frank was one of the most complex and tragic figures in the modern design era. His work defies easy categorization: his best designs combined simple, even severe, lines with lush, textured upholstery. Yet he could also deliver pieces modeled on classic forms like the klismos chair. As Buresh explains, Argentina between the world wars had become an economic powerhouse, and many of the country’s elites divided their time between Paris and Buenos Aires. In the former city, they became familiar with the work of Frank, scion of a wealthy yet ill-starred banking family, and eagerly bought his pieces. In the 1930s the Argentine design firm Comte began to import his works and later to produce them. At the outbreak of World War II, Frank moved to Argentina, where he executed a number of important commissions. In early 1941 he traveled to New York, evidently in hopes of rekindling a romantic tie he’d forged in Paris. He met with disappointment and committed suicide. As Cecil Beaton said: “If Frank had lived, he would perhaps have been the great decorator of the future.”

JEAN-MICHEL FRANK IN ARGENTINA By JAMES BURESH

Gallery BAC, 120 pages, $40