Design

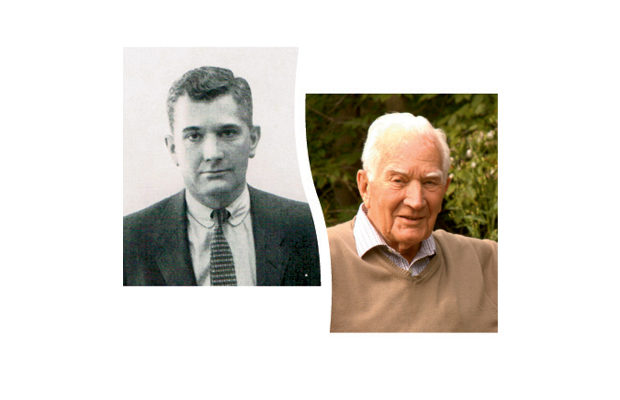

Designer Spotlight | Jens Risom

FOR SEVEN DECADES NOW, THE DANISH-BORN DESIGNER HAS BEEN DEVISING FURNITURE THAT MELDS BEAUTY AND UTILITY

On December 9, Danish-American furniture designer Jens Risom passed away at the age of 100. As one of the first to introduce Scandinavian design to the United States, his legacy will continue to influence the world of design far beyond his own lifetime. Below is a feature on Risom first published in the Spring 2012 issue of MODERN, reproduced here in memory of one of the last greats of mid-century design.

Today Risom, ninety-five, likes to sit in a rocking chair, but that’s not because his designing days are over. In fact, the rocking chair (in his apartment in New Canaan, Connecticut) is one that he designed about four years ago for Design Within Reach stores. Other recent designs, including a luxurious origami-like club chair, are available from Ralph Pucci International in New York, while Rocket Gallery in London is manufacturing Risom designs of half a century ago for the European market. Risom has been rediscovered, and fortunately he is around to enjoy it and to extend his distinguished career.

“Something new seems to be coming along all the time,” he observed in a recent telephone conversation. “I am pleased with that, especially at my very, very high age.”

He moved not long ago with his wife, Henny, to an apartment complex for the elderly that is a short distance from the house where he had lived since the 1950s. Earlier, at a visit to that house, he showed off the rocking chair, pointing to its generous size, good lower back support, and overall comfort, rather than to its appearance. Risom is still a functionalist after all these years.

A nod to the classic Danish modern aesthetic that can be found in all of Risom’s work, the Risom Rocker from 2009 is available exclusively at Design Within Reach.

Risom was born and schooled in Denmark, and for three years, ending in 1938, he studied furniture design at the School of Arts and Crafts in Copenhagen along with Hans Wegner and Borge Mogensen, two of the pre-eminent designers of mid-century “Danish modern” furniture. But Risom has lived in the United States since 1939, and he is so American he pronounces his first name with an English hard J sound, rather than the Danish Y sound. (The last name is pronounced “reesum.”)

“I came because I believed that this was a very exciting country,” he recalls. “What I found was that it was advanced in just about all areas—except for taste.” Nobody was making the kind of furniture he wanted to design because it was believed that nobody would buy it. His challenge was not simply to find work, but to find craftsmen to produce his furniture, merchants to sell it, and people to buy it. He spent nearly two years working with a decorator and gaining a modest profile. In 1941 he met Hans Knoll, a German who had started a company to make modern furniture in America.

“He was looking for me, and I was looking for him, but neither of us knew it.” Knoll needed a designer on hand who could respond to opportunities, while Risom viewed Knoll as a “super-super-salesman,” who could get the word out. For several months Risom and Knoll staged what Risom calls “a traveling circus,” crisscrossing the country in a Plymouth convertible, stopping at architects’ offices and small retailers, introducing themselves to the small, far-flung community of people with modernist tastes. Periodically they would get an order, and Risom would grab a drawing board and design a new piece.

In 1941 Europe was already at war, and, Risom says, even here, materials and products used in furniture were being diverted to military use. It seemed like a terrible moment to start making a new kind of furniture, but in fact, the upheaval worked to Knoll’s and Risom’s advantage. This is when Risom did what is still his most famous design—the web-seated Lounge chair.

“The material of the webbing was needed for parachute harnesses,” Risom explains. But Risom found that it was possible to buy webbing that the military had rejected. “It was all olive drab at first, but then we figured out how to bleach it and dye it. Black was good.” The first chairs were maple, but they were designed to make use of whatever wood was available.

Thus, wartime shortages shaped the chair, and they also removed much of its competition. America’s entry into the war led to the opening of large numbers of clubs and other recreational facilities for soldiers, and Risom’s chair was one of the few available. Knoll, and the modern American furniture industry, were in business.

In 1943, however, Risom was drafted into the U.S. Army and was sent to Europe. During this period Knoll, who did not have to serve for health reasons, met Florence Schust, who subsequently became his second wife and business partner. “She was more interested in metal and plastic,” says Risom, who has nearly always worked with wood. In 1946 Knoll and Risom ended their association, and a few years later, Knoll stopped making Risom’s designs. (In 1990 the Knoll firm revived production.)

In 1946 Risom created his own company to design and manufacture high quality modern furniture, first for homes, then later, primarily for offices, which he sold in 1970. His own home is full of his pieces, starting with a cabinet he made when he was seventeen and continuing to his latest designs. It is almost impossible to guess when any of them were made. Everything is direct, pragmatic, and elegant.

Risom favors designs that can adapt. Among the pieces in the line for Rocket is a coffee table that, with the addition a three-quarter-length cushion, becomes a bench with end table. There is also a coffee table with a slot and a magazine rack at one end to enable quick clearing and serving.

His company came to specialize in cabinets, of which he is very proud, but he is happy to see that designs for his chairs, tables, and benches are being revived. Chairs, especially, he notes, go beyond pure utility and touch the emotions. “The function of a chair is to support the body properly,” he says, pointing once again at the 1941 web-seated Lounge chair. “This chair is not more comfortable than other chairs. But the sweep of it makes you feel that it will be comfortable.”