Design

A Winter’s Worth of Reading

BOOKS THAT EXPLORE THE WIDE WORLD OF DESIGN

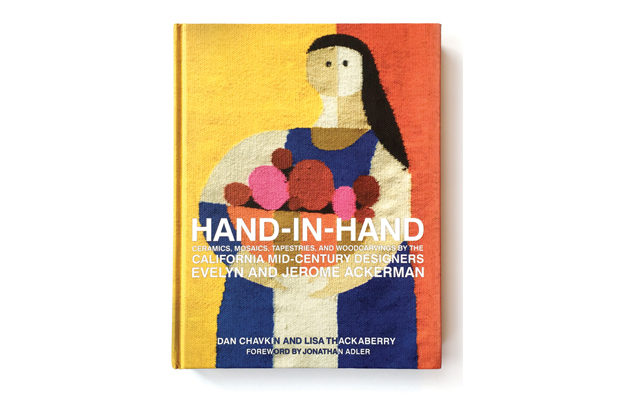

Hand-in-Hand: Ceramics, Mosaics, Tapestries, and Woodcarvings by the California Mid-Century Designers Evelyn and Jerome Ackerman By Dan Chavkin and Lisa Thackaberry, Pointed Leaf Press, 240 pages, $55

HAND-IN HAND is the first monograph about the California mid-century design team of Evelyn and Jerome Ackerman. In his preface designer Jonathan Adler describes the couple’s work as the “perfect marriage of gorgeous design, impeccable craftsmanship, emotional sincerity, and unfiltered childlike wonder.”

Jerome (Jerry) Ackerman met his future wife in the winter of 1948 in his hometown of Detroit. On the advice of a friend, the twenty-eight-year-old World War II vet decided to pay a visit to the girl he’d met once and walked into the interior design studio where she worked, armed with only his charm and two candy bars in his pocket. They were married that fall. As children of the Great Depression they knew the value of frugality, self-reliance, and education; newlyweds, they both earned degrees in the arts from Wayne State University with GI supplements, and they built the furniture and decor for their first apartment.

In 1952 they moved to Los Angeles seeking new opportunities and sunshine. They believed in the intersection of art, design, and mass production espoused by the Bauhaus movement, and “hand-in-hand” mastered ceramics, mosaics, textiles, woodcarving, and metalwork. Their inventive and whimsical style set them apart, as did their commitment to the idea that great design should be affordable and accessible. Though their oeuvre is now seen as the epitome of California mid-century modernism, when Jerry (who retired four years ago) was asked which project gave him the most pride in his long career, he responded, “marrying my wife.” Hand-In-Hand features many never-before-seen preparatory drawings and color guides, and tells the heartwarming story of a partnership in design and life.

Midcentury Houses Today By Jeffrey Matz, Lorenzo Ottaviani, and Cristina A. Ross, Photography by Michael Biondo, Monacelli Press, 240 pages, $65

A GRAPHIC DESIGNER, two architects, and a photographer present an in-depth look at sixteen of the more than one hundred modern houses built by the so-called Harvard Five in New Canaan, Connecticut, between 1950 and 1978. A suburb just forty-five miles from Grand Central—and more New England than New York—New Canaan became an affordable reprieve in the 1940s and 1950s for executives working in the city. There—following the teachings of their Harvard professor, Bauhaus founder Walter Gropius— John Johansen, Marcel Breuer, Landis Gores, Philip Johnson, and Eliot Noyes built houses for themselves and their clients that expressed the simplicity, openness, sensitivity to site and nature, and use of natural materials that formed the core principles of modern- ism as the ideal of twentieth-century domesticity.

Every year design enthusiasts make the pilgrim- age to this longstanding shrine of mid-century architecture, where ninety-one of the 118 modernist houses originally built still survive. This book looks at sixteen of them in detail to study the range of approaches that have led to their preservation and adaption to contemporary life; each house has a chapter of its own, with floor plans, archival shots of initial construction, and new photography of additions made by significant contemporary architects, such as Toshiko Mori, Roger Ferris, and Joeb Moore. Included, too, is a comprehensive timeline of the most famous projects, not only by the Harvard Five but also by Victor Christ-Janer, Edward Durell Stone, and Alan Goldberg. The book took five years to complete, with commentary from the architects and builders, the original owners and current occupants, that reveals how these houses are enjoyed and lived in today, and how the modernist residence is more than a philosophy of design and construction, but also a philosophy of living.

Sottsass By Philippe Thome? Phaidon, 500 pages, $150

ETTORE SOTTSASS is best known as the founder of the 1980s Italian design collective Memphis, which produced colorful, symbolic, and playful office equip- ment, furniture, glass, lighting, and jewelry. He was also a non-conformist architect and writer as well as an avid photographer who shot portraits of Hemingway, Picasso, Ernst, and Chet Baker. Divided chronologically, with multicolored tabs separating sections, this massive and beautiful volume traces Sottsass’s prolific career and explores his methodology. The reader literally unfolds eight hundred illustrations that have been cleverly tucked inside, including drawings and sketches and never-before-published photographs from the Sottsass archive. In addition, there are five short essays by experts that explore Sottsass’s work in architecture, graphic design, photography, industrial design, and collector’s editions.

A prisoner of war during World War II, Sottsass set out to create design that would help people become aware of their existence, the spaces they live in, and their own presence in them. He cared little about functionality and was more intent on creating design with meaning and addressing the hopes and dreams of his generation. The author reserves three full pages for images of one of Sottsass’s most famous pieces, the bright red plastic Valentine portable typewriter for Olivetti that hit stores on February 14, 1968. Sottsass deemed it the “anti-machine machine,” meaning that it functioned as a typewriter but also had a human quality lacking in most office equipment at the time. “Red is the color of the Communist flag, the color that makes a surgeon move faster and the color of passion,” he proclaimed. This book is itself a piece of art, with a Tiffany-blue bifold cover and a dapper black-and-white striped lining worthy of Sottsass.

Monsieur Dior: Once Upon A Time By Natasha Fraser-Cavassoni, Pointed Leaf Press, 252 pages, $70

MONSIEUR DIOR: ONCE UPON A TIME by the Paris-based fashion journalist Natasha Fraser-Cavassoni, offers an exclusive behind-the-scenes look at the ten years during which Christian Dior ran his esteemed house. The book begins with his February 1947 show that took the fashion world by storm with his “New Look.” At a time when women were craving beauty and glamour following the war. Dior’s New Look brought femininity back to fashion with a bold use of fabric, silhouetted lines, and shorter hemlines. In the short time that Dior ran his house he expanded his empire to include perfumes, jewelry, and hosiery while opening boutiques all over the world. Fraser-Cavassoni inter- views dozens of people who knew Dior personally, including fellow designer Pierre Cardin, who worked in the Dior ateliers at the time of the 1947 show, as well as Lauren Bacall just months before her death. “When Dior made the change of how women should look, you couldn’t ignore it,” Bacall said, “because his New Look made everything else look old-fashioned.” Marlene Dietrich’s daughter recounts how her mother famously proclaimed in a telegram to Alfred Hitchcock regarding her role in his upcoming Stage Fright, “no Dior, and no Dietrich.”

There have been numerous scholarly books written about the genius of Dior, but Monsieur Dior: Once Upon A Time is a refreshing departure, humanizing this design icon, and told in the words of his friends, favorite models, and employees. Photography by legends such as Cecil Beaton, Henri Cartier-Bres- son, Lord Snowdon, and Willy Maywald, as well as never-before-seen materials from the Dior Archives, contribute to this delightful look into the House of Dior’s brilliant founder.

The Best of Flair Edited by Fleur Cowles, Foreword by Dominick Dunne, Rizzoli, $125

FLEUR COWLES was an American expatriate painter, philanthropist, and founding editor of the short-lived Flair, launched in 1950, one of the most outrageously beautiful and inventive magazines ever created. The Best of Flair is packaged in an elegant scarlet box that match- es the color of the inaugural issue’s die-cut cover with its single golden wing. Based on a brooch Cowles had discovered in a Paris flea market, the design was intended to symbolize “flight, excitement, and beauty” and embody the content to be found in each issue of the magazine. Cowles handwrote every editor’s letter in gold ink, painstakingly selected the best images, used only the finest papers, and of course ensured that each cover was absolute perfection with a spectacular cutout. “I decided on a two-part cover with a hole,” she wrote, “because I like the mystery of not being able to know what’s inside. Of course, people started calling it ‘Fleur’s hole in the head.’” The eleven issues Cowles produced were lauded for their fashion coverage, literature, art, travel, theater, and humor. Flair was not just a magazine but an art form, with features about and interviews with some of the world’s most legendary artists and celebrities—Lucian Freud, Jean Cocteau, Tallulah Bankhead, Salvador Dali?, Simone de Beauvoir, Walker Evans, James Michener, Ogden Nash, Gypsy Rose Lee, Clare Boothe Luce, George Bernard Shaw, Margaret Mead, and Tennessee Williams, among others. Now more than fifty years after the magazine ceased publication, this ingenious compilation by Rizzoli includes multiple gatefolds incorporating die-cuts, pop-ups, booklets, and accordion folder leaflets.

Frank Lloyd Wright: The Rooms: Interiors and Decorative Arts By Margo Stipe, Photography by Alan Weintraub, Foreword by David Hanks, Rizzoli, 336 pages, $75

THE EVOCATIVE INTERIOR SPACES created by Frank Lloyd Wright, starting with his own Oak Park home and studio built in 1890 and concluding with his last additions to Taliesin III, are explored in this lavishly illustrated book. The author describes Wright as an idealistic iconoclast who believed in creating democratic architecture and thought individuals deserved spaces that would encourage them to develop their full potential. Thus, he broke up boxlike Victorian rooms to create free- flowing interior spaces. A proponent of the Gesamtkunstwerk (total work of art) in architecture, he also designed the furniture for his houses—tables, bookcases, easy chairs, sofas, cabinets, rugs, murals, and stained glass. One chapter is dedicated to Wright’s great- est inspiration and muse, nature. “He believed nature was the materialization of spirit,” Stipe writes, and designed “structures that belonged to the site, that did not destroy the life of the site, but improved on it.” Wright’s career changed and evolved with each decade, and he was still building actively when he died at ninety in 1959. This volume provides a clear view of his organic blend of architecture and ornament and highlights a number of his masterpieces—from the Prairie period to the 1950s—including the Frederick C. Rob- ie House, the Susan Lawrence Dana House, and, of course, Fallingwater, designed for Edgar and Liliane Kaufmann.

Beautiful Users: Designing for People Edited and designed by Ellen Lupton, Princeton Architectural Press, 144 pages, $21.95

THE COOPER HEWITT, Smithsonian Design Museum reopens this month after a three-year renovation (see p. 78). One of the inaugural exhibitions is Beautiful Users, curated by Ellen Lupton, the first in a series of shows to be held in the new Design Process Galleries and in- tended to showcase the people and methods that define design as an essential human activity. This accompanying book explores the ethos of “designing for people” a phrase coined by Henry Dreyfuss, the father of industrial design, after World War II. The book opens with a brief history of Dreyfuss’s telephone designs, his user-centered approach that focused on studying behavior to develop successful products.

Designs featured range from Yves Behar’s pill dispenser to the Nest Learning Thermostat, and include Smart Design’s Good Grips for OXO, 3-D-printed prosthetic Robohands, and Eva Zeisel’s flat- ware, to name a few. But this is more than a companion guide for the exhibition. It is a valuable resource that explores a range of design practices, from user research to hacking, and also contains a critical glossary of terms.