In Mabel’s sun-filled studio, an Alvar Aalto lounge chair from MoMA’s original members’ lounge and, to the right, an Aalto drawer unit from the museum’s offices. | Photography by Jenny Gorman

In Mabel’s sun-filled studio, an Alvar Aalto lounge chair from MoMA’s original members’ lounge and, to the right, an Aalto drawer unit from the museum’s offices. | Photography by Jenny Gorman

Feature

Art House

WITH STACCATO MID-ATLANTIC DICTION, a radio announcer says, “There’s something going on now, up there on 53rd Street and Fifth Avenue.” It’s December 1949 and what’s going on is the Children’s Holiday Carnival at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, an initiative conceived by the museum’s founding director of education, Victor D’Amico, a man with an exceptional ability to adopt a child’s eye view. “If a four-year-old comes into the museum, he sees practically nothing,” D’Amico explains to the host. “He sees the bottoms of paintings or, more so, he just sees adult legs.” For four to eight-year-olds only, the carnival allowed children to experience art unobstructed by appendages or rules.

Over a five-decade career, D’Amico would nurture the artistic impulses of generations of young people, among them a teenaged Diane Arbus and longtime MoMA curator William Rubin. Today D’Amico’s unique vision continues in the forms of the Children’s Art Carnival in Harlem and the Art Barge art education center in Amagansett, Long Island. His remarkable legacy is preserved in the MoMA archives. But his inimitable spirit permeates the Victor and Mabel D’Amico Studio and Archive, housed in the residence in Lazy Point, Long Island, that D’Amico built with his wife, collaborator, and fellow art educator, Mabel.

While the carnival evolved over the years, the idea was always the same: with the guidance of museum educators, children could not only see but also touch the art, and engage with a series of educational tools devised by D’Amico, such as the Color Player, a machine that produced an array of color effects at the touch of a keyboard; a perforated panel on which children manipulated string and pegs to learn about tension and line; and a lazy Susan–like rotating tray that offered collage materials while it taught sharing. And then, in a flurry of colored paper, clay, wire, and paint, they could create. “After a child has been inspired, so to speak, he has to go and try the thing out for himself,” D’Amico said in the 1949 radio interview.

In the following years, D’Amico would bring the art carnival to Milan and Barcelona, to the World’s Fair in Brussels, and on a tour of India with Jackie Kennedy. In the 1949 radio broadcast, the host wraps up the interview: “Well, you know the one thing that’s bad about this, Mr. D’Amico, and it’s very bad. . . it sounds so inviting and so interesting and then [you] tell us the adults have to stay out.”

If D’Amico barred adults from the carnival, he offered an example of how they could apply its principles: through his work at the museum and from the world at large, he plucked and gathered ideas to try things out for himself. Much of this ingenuity surfaced in the house at Lazy Point.

The D’Amicos had a Manhattan apartment a short walk from the museum, but they began looking for a summer home in 1940. Taking up a local’s offer to show them the best property in Lazy Point, they were led to a site overlooking a marsh and a lagoon, and beyond, an island bird sanctuary across the harbor. A construction project deserted along with the property was more of a boon than a bother: Victor and Mabel would integrate the cinder blocks and support beams into their own construction.

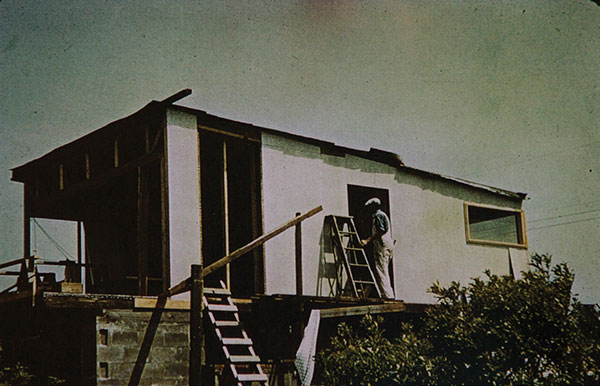

Owing as much to the couple’s sensibilities as to wartime shortages, they also purchased and dismantled another abandoned building to reuse its materials in their residence. And, true to form, they did the work largely themselves, from the foundation up, learning how to build a house as they went along and, when necessary, enlisting the assistance of local tradesmen (including a carpenter nicknamed Dirty Shorty). Mabel pulled the nails from the salvaged wood and hammered them straight for reuse; together the couple poured concrete; and when they needed more hands, they promised Victor’s museum colleagues a weekend at the beach in exchange for a little manpower. For the two summers it took to complete the house, the couple threw a tarp over its frame and camped out.

The initial result—for a decades-spanning work-in-progress—was a modest twenty-five square-foot box capped by a gently sloping single-planed roof. Its interior was spartan but cheerful—Victor, always interested in color, painted the ceilings in vibrant De Stijl– and Bauhaus–inspired primaries, with secondary colors on smaller surfaces—with functional elements such as storage bins on casters that rolled out from under the stairs, pegboard ceilings, and built-in open shelving that maximized space in the small kitchen.

From its original form, the house developed and expanded. In the early 1950s, inspired by Philip Johnson’s Glass House, built while Johnson was a director of the museum’s department of architecture and design and a colleague of Victor’s, they added a large room to the ground floor, extending the house toward the beach. In a photograph taken during construction, Jackson Pollock, a Long Island neighbor, sits on a sawhorse, squinting in the sunlight toward Victor, who, mouth pursed around a pipe, builds the window frames that would run along three sides; receding behind them, the brush, the beach, the marsh, and the harbor. It was Pollock who suggested dropping the expansive windows to meet the floor, joining the room with the continuum of the landscape.

As the house evolved, so did its interior, becoming an assemblage of modern furnishings and eclectic objects combined as if the residence itself were a readymade. Much of the furniture came from the Museum of Modern Art, including a pair of black-lacquered dining tables reincarnated from their prior life in the trustees’ boardroom. Custom-built for the museum’s opening in 1929, they were discarded and rescued in the 1960s. An Alvar Aalto filing cabinet from the museum’s offices followed a similar trajectory and ended up in Mabel’s studio, along with an Aalto chair from the museum’s members’ lounge. And four Eames Molded Plywood chairs also came from the museum. The numbers on the bottom of each, where manufacturer labels would later appear, suggest these examples had a unique history. Mabel improved on one by upholstering the seat with foam padding and faux fur.

The D’Amico collection of objects grew as they traveled with the art carnival—in the days before jet planes, flying to Madrid or Barcelona or Brussels, not to mention India, meant several stops along the way and Mabel made a policy of spending any leftover currency. She also cultivated a glass collection that included bottles and fragments washed up on the beach, but also vessels from ancient Persia and art glass made in nearby Sag Harbor. Today, these objects congregate here and there: an assortment of wood utensils hangs in a line above the kitchen sink, and glass bottles, grouped by color, sit on every sill. They are joined, in every room, by Mabel’s found-object constructions—made of bits of glass, wire, driftwood, and concrete—that make the house a riotous and creative composition, an art carnival in itself.

Victor died in 1987 and Mabel in 1998. She left their home to the Victor D’Amico Institute of Art, which today maintains it as a house museum and archive. For information on visiting the Mabel and Victor D’Amico Studio and Archive, visit theartbarge.org/house.

Jenny Florence writes about design, architecture, and art from her apartment in Brooklyn.